Opinion: Digital Nomadism and Gen Z

Career choices are increasingly reshaped by flexibility, with a growing focus on enjoying work rather than merely simply enduring it

By Shanaya Vas, Dr Garima Rajan

There is nothing that unsettles Gen Z — expected to make up 27 per cent of the labour force in OECD nations by 2025 — more than the prospect of a 9-to-5 desk job. Career choices are increasingly being reshaped by flexibility, with an emphasis on enjoying what one does rather than simply enduring work. This is where the phenomenon of digital nomadism comes in.

The term ‘digital nomad’ was introduced by Makimoto and Manners in 1997 to describe how technological advancements enable people to work remotely while travelling (Hannonen, 2020). There are several nuances in the definition of digital nomadism, but in this context, the one provided by Bozzi (2020) is the simplest and apt. He defined it as “Internet-enabled remote workers, who maintain a focus on connectivity and productivity even in leisure.” In essence, it reflects the convergence of work, technology, and travel, and for Gen Z, a generation already sceptical of hustle culture, this model seems like the ideal fit.

The pandemic accelerated this shift, breaking myths about productivity while working remotely. In India, the rise of startups and younger founders has further normalised this culture. Understanding this trend requires exploring the psychology driving Gen Z’s choices and asking how organisations can adapt in concrete, actionable ways.

Psychology of Digital Nomadism

The Self-Determination Theory emphasises that true motivation arises from having control over one’s environment, and hence autonomy plays a key role. In a study on Gen Z work motivation, the need for autonomy was expressed through desires for influence, trust, clarity, and diversity.

Conversely, factors such as insignificance, micromanagement, uncertainty, and enforced homogeneity were found to diminish motivation (Wennqvist, 2023). Hence, digital nomadism, by allowing freedom over when, where, and how to work, directly fulfils the need for autonomy.

The growth of startups, IT services, and gig platforms has made location-independent work and the nomadic lifestyle more accessible to young professionals in India

Work-life integration and burnout avoidance are pressing drivers for flexible workplaces today. “A 2022 Mind Share Partners study found that 83 per cent of Gen Z respondents had quit jobs due to mental health reasons, the highest across any generation. Similarly, the Deloitte Millennial and Gen Z Survey in 2021 reported that 77 per cent of Gen Z experienced exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy, far higher than the global average of 63 per cent.” (George, 2024). These findings highlight not just individual struggles but an emerging “anti-hustle” ethos, where Gen Z actively rejects the grind culture.

Self-actualisation through personal growth also explains why Gen Z wants to integrate work with recreational activities. Unlike previous generations that prioritised stability or salary, they find meaning in pursuing interests and varied experiences. This also correlates with the belief that “digital nomads place themselves at the top of the pyramid, in the self-actualisation phase of their lives” (Canas, 2022). The ability to work from new places, engage in different challenges, and align work with personal aspirations enables a sense of fulfilment that static office roles often fail to match.

Novelty-seeking underlines the appeal for travel and leisure alongside professional responsibilities. Gen Z shows higher levels of openness to experience (a Big Five personality trait) and actively seeks environments rich in novelty, such as new people, cultures, and tasks.

The Indian Context

In India, these psychological attitudes toward digital nomadism intersect with a rapidly changing economic landscape. The growth in start-ups, IT services, and gig platforms has created fertile ground for location-independent work, making the nomadic lifestyle more attainable than ever for younger workers in India.

However, this appeal collides with deep-rooted traditional expectations. Families often prioritise stability, steady income, and career paths that align with marriage timelines, creating tension between cultural norms and personal aspirations.

Additionally, supportive policy infrastructure, such as clear taxation rules and labour law frameworks, continues to lag. As a result, digital nomadism in India remains both aspirational and contested, highlighting the urgent need for organisations to bridge this gap through thoughtful policies while navigating local realities.

How Organisations can Adapt

Three actionable strategies can help balance flexibility with productivity.

- Work from Anywhere (WFA) frameworks: These can legitimise mobility while maintaining organisational cohesion. Companies could allow employees to officially work remotely from any location for a fixed number of months each year, creating predictable yet flexible arrangements. This also resonates with Gen Z’s strong preference for autonomy.

- Shift toward outcome-oriented performance metrics: Traditional time-based measures like 9-6 logins do not align with the mobile, results-driven goals. Instead, organisations should prioritise deliverable-based evaluations using digital project management tools that emphasise accountability without surveillance. As George (2024) notes, parameters like innovation, collaboration, or leadership engagement better capture Gen Z’s success in digital contexts than outputs like sales or clients alone.

- Structured technological, relational support: Companies should offer stipends for portable technology, strong internet connections, and wellness resources to maintain productivity. Equally important is relational infrastructure, in the form of mentorship and peer networks. This can mitigate risks of isolation and burnout, which are often cited as the downsides of remote work.

Natural Extension

For Indian Gen Z, digital nomadism is not merely a workplace trend but a reflection of deeper psychological drivers. This generation is reshaping work to align with personal values, rather than traditional linear career paths. Digital nomadism, therefore, represents a natural extension of Gen Z’s preference for self-determination, novelty, and fulfilment.

However, this model is not without its limitations. Certain industries, such as manufacturing, healthcare, and on-site services, cannot easily accommodate location-independent work. In the Indian context, cultural expectations, gender, and family dynamics may further slow acceptance of nomadic lifestyles. Societal norms often make it easier for men to embrace mobile work, while women may face greater scrutiny or safety concerns when travelling frequently.

Similarly, individuals with spouses or young children encounter practical barriers, such as schooling continuity and caregiving responsibilities, which make sustained nomadism more challenging. From an organisational perspective, challenges of trust, monitoring performance, ensuring legal compliance, and protecting data security remain persistent debates.

Despite these drawbacks, digital nomadism reflects a generational redefinition of work that organisations must recognise. By adopting forward-looking policies, employers can strike a balance between mobility and productivity.

(Shanaya Vas is a Psychology Major Undergraduate Student, and Dr Garima Rajan is an Assistant Professor of Psychology, FLAME University, Pune)

Related News

-

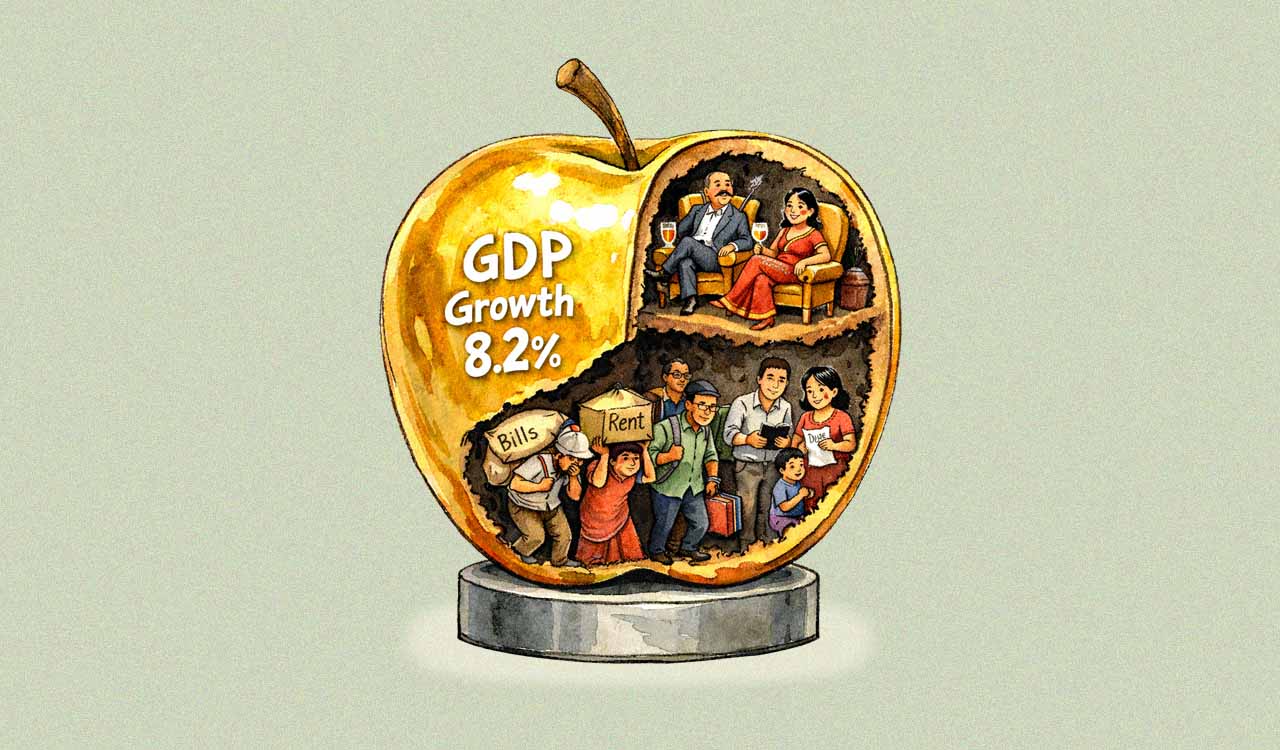

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Australia offers refuge to Iranian women footballers amid war

26 mins ago -

Editorial: Nepal rejects the old guard

1 hour ago -

Telangana: Error mars Inter Physics II paper; question goes missing

1 hour ago -

Three-member burglar gang arrested in Hyderabad, stolen property worth Rs 13 lakh recovered

2 hours ago -

ACB catches Kukatpally community organiser taking Rs 18,000 bribe

3 hours ago -

90% of Hyderabad eateries likely to shut down in next 48 hours amid LPG crisis

3 hours ago -

Watch | Flash Strike by Sanitation Workers After CM Revanth Reddy’s Remarks

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Overseas consultancy manager murdered in Madhuranagar office attack

3 hours ago