A crack in the bell of liberty

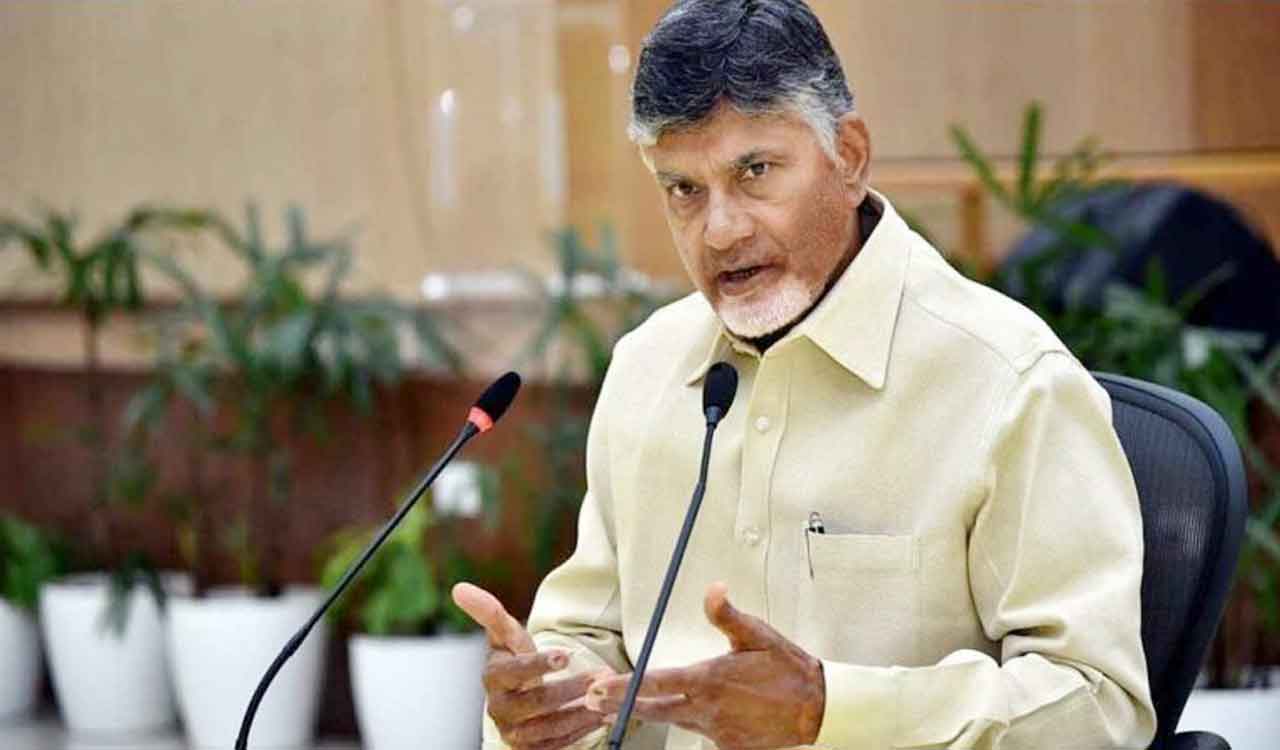

Andhra Pradesh GST officer Siddharthi Subhas Chandrabose was suspended for posting Amaravati flood photos on Facebook, sparking debate on administrative overreach, selective enforcement, and freedom of expression, highlighting tensions between bureaucratic discipline and democratic dissent in the Naidu government.

By Naresh Nunna

In a striking display of administrative overreach, the Andhra Pradesh government has suspended GST Assistant Commissioner Siddharthi Subhas Chandrabose for posting flood photographs on Facebook. His “crime”? Documenting waterlogged Amaravati fields after rainfall and questioning the wisdom of building a “drone capital” in a flood-prone area.

Subhas’s August 18 posts were hardly seditious—merely sardonic observations about Amaravati’s vulnerability to monsoon waters. His suggestion that the capital might function better “as a reservoir” was crude humour, not calculated malice. Yet the Chandrababu Naidu administration, displaying the thin skin characteristic of defensive governments, branded these posts “false propaganda” aimed at fomenting “hatred against Amaravati.”

The September 23 suspension order reveals a government so insecure about its flagship project that it cannot tolerate even mild mockery from a mid-level bureaucrat. This heavy-handed response raises uncomfortable questions: If Amaravati’s resilience cannot withstand a GST officer’s Facebook critique, how will it withstand actual floods?

Legal Scaffold of Silence

The government’s suspension finds legal cover under Rule 9 of the All India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1968, which prohibits civil servants from making statements that constitute “adverse criticism” of government policy. Subhas’s flood photos and reservoir quips technically breach this provision, giving the administration sufficient grounds for disciplinary action.

This legal framework grants governments sweeping powers to silence dissenting voices within the bureaucracy. The suspension process, while nominally subject to natural justice principles, operates with such broad discretion that virtually any critical expression can be reframed as “misconduct” or action “prejudicial to public interest.” The law’s elastic interpretation ensures that administrative discipline trumps individual expression, creating a chilling effect that extends far beyond this single case.

Irony of Selective Criticism

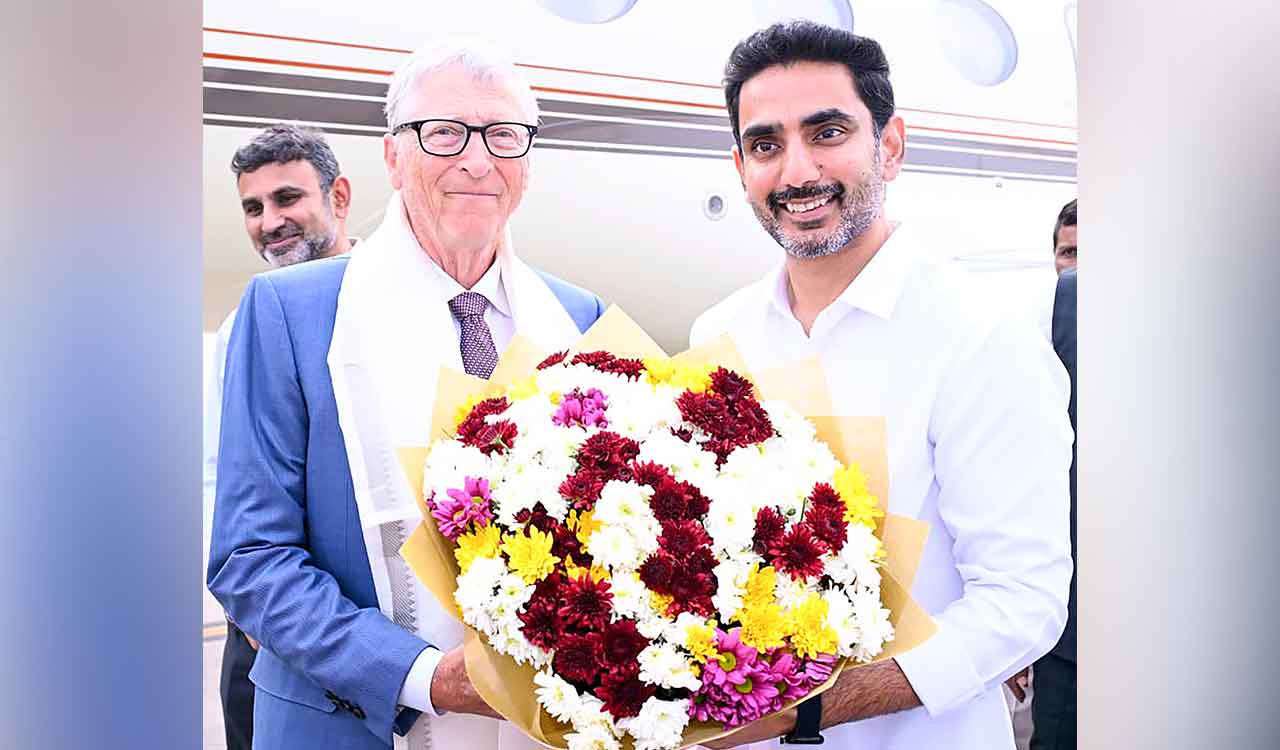

The suspension is particularly jarring when viewed alongside Chief Minister Naidu’s own public pronouncements. At a collectors’ conference in Amaravati on September 17, 2025, Naidu felt emboldened to brand Jawaharlal Nehru—India’s first Prime Minister and architect of modern democracy—as “feudal,” dismissing him as a privileged “wealthy landlord” who enjoyed luxuries like “a car in London.”

Here lies the administration’s glaring double standard: while a GST officer faces suspension for posting flood photographs, the Chief Minister himself indulges in sweeping historical revisionism, reducing one of democracy’s towering figures to a caricature of aristocratic excess. If adverse criticism of leadership merits disciplinary action, why does this principle apply only downward in the hierarchy?

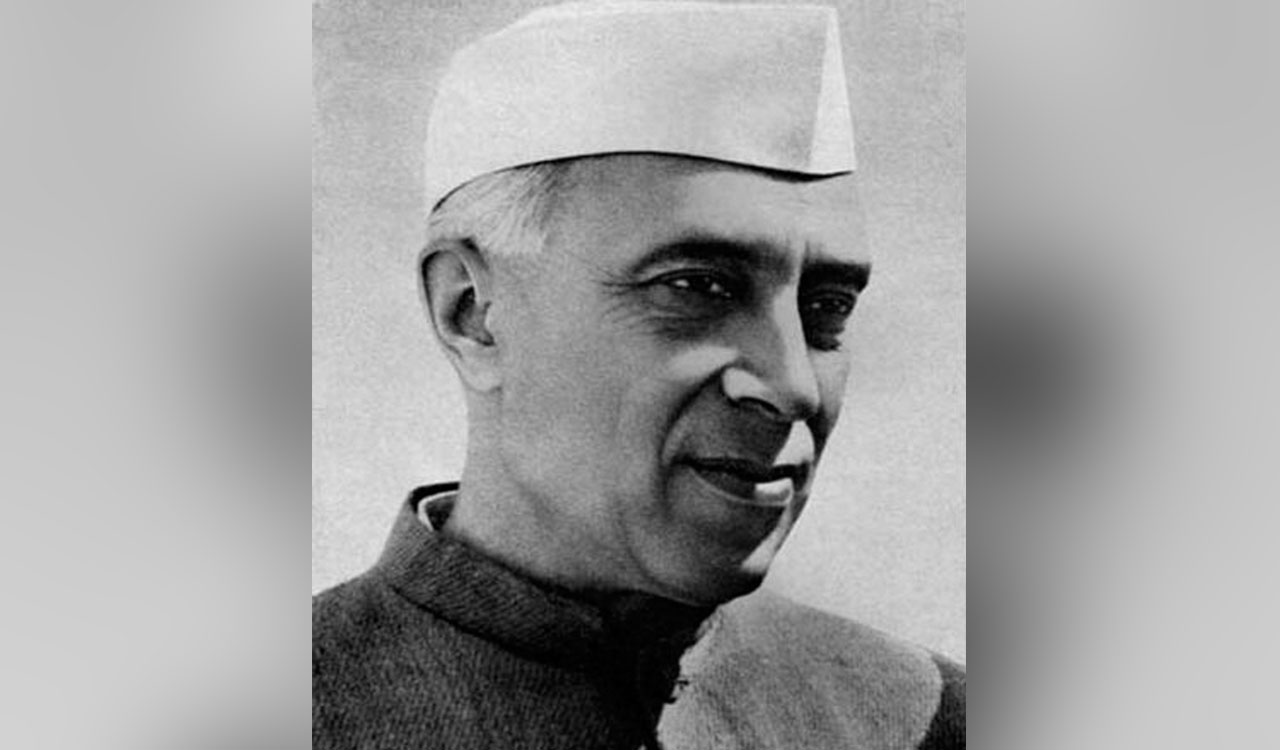

Naidu’s casual dismissal of Nehru as a “feudal wealthy landlord” reveals a stunning ignorance of democratic history. Nehru was the very architect of India’s culture of free expression—the same freedom that ironically allows Naidu to make such pronouncements without consequence.

Consider Nehru’s legendary relationship with cartoonist Shankar, whose satirical magazine lampooned the Prime Minister in over 4,000 cartoons. When Parliament erupted over Shankar’s infamous “ballroom dancing” cartoon depicting MPs with donkey heads, demanding apologies, Nehru’s response was characteristic: he defended the cartoonist’s right to satirize power. His standing instruction—”Don’t spare me, Shankar”—embodied a democratic maturity that seems utterly alien to contemporary political culture.

Nehru understood what Naidu apparently cannot: democracy thrives on dissent, criticism, and even ridicule. Satirical attacks were not threats to be crushed, but mirrors reflecting power’s follies. When Shankar’s follow-up cartoon depicted MPs as an entire menagerie of animals rather than just donkeys, Nehru did not unleash administrative fury—he appreciated the wit.

This is the “feudal landlord” Naidu so casually denigrates: a leader who institutionalised tolerance for criticism, encouraged rather than suppressed satire, and understood that genuine strength lies in accepting scrutiny rather than silencing it.

Chanakya Chronicles

Nehru’s democratic maturity extended even further through his pseudonymous writings as “Chanakya.” In 1937, he penned a scathing self-critique in Modern Review, describing his own “intolerance of others,” “formidable conceit,” and warning that “Jawaharlal might fancy himself as a Caesar.” He dissected his own capacity for demagoguery, noting how he could manipulate crowds “like a god, serene and unmoved by the seething multitude.”

This was not mere intellectual exercise—it was democratic prophylaxis. Nehru recognised that power corrupts through the “intoxicating glamour of infallibility” and deliberately inoculated himself against authoritarian temptations by publicly examining his own megalomaniacal potential. He warned against leaders who “might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism” while becoming fascists—a comprehension of democratic decay decades ahead of its time.

Here was a leader so secure in his democratic convictions that he anonymously attacked his own leadership style. When friends chastised him for “running himself down,” Nehru replied that he refused to let others imagine him “as something nobler, perhaps more mysterious, more complicated” than he actually was.

Dwarfish Contrast

What moral authority does Naidu possess to critique a leader who voluntarily subjected himself to harshest scrutiny? A man who suspends a GST officer for posting monsoon photographs dares to judge the architect of Indian democracy, who welcomed cartoons and criticism of himself. This is not merely political disagreement; it is intellectual bankruptcy masquerading as statesmanship.

Naidu’s actions disqualify him from invoking Nehru’s name. A leader who cannot tolerate flood photographs on Facebook has no standing to evaluate one who encouraged cartoonists to depict him as everything from Caesar to donkey-headed dancers. The very fact that Naidu can publicly malign Nehru without consequence is itself a testament to the democratic freedoms Nehru established—and that Naidu now systematically erodes.

The suspension of Subhas represents not governance, but its antithesis: petty tyranny by small minds drunk on administrative power. Leaders who punish subordinates for mild criticism while launching vitriolic attacks on democratic icons reveal fundamental unfitness for public office. They mistake the trappings of authority for genuine leadership, confusing the ability to silence with the right to rule.

(Author is a senior journalist based in Hyderabad)

Related News

-

Hyderabad: Punjagutta Police arrest salesman for stealing 1 kg gold from Joyalukkas

1 min ago -

Supreme Court advises caution in pre-marital relationships

2 mins ago -

Delhi High Court grants temporary relief to Rajpal Yadav in cheque cases

6 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Cybercrime Police arrest three in Rs 19 crore USDT fraud

6 mins ago -

MBBS student from Bihar found hanging in Bengal hostel

11 mins ago -

UoH partners with MNJ Institute to advance personalised Cancer care

13 mins ago -

TN BJP chief challenges Vijay to spell out party policies

16 mins ago -

Osmania University to host AIU Central Zone Vice Chancellors’ Meet 2025–26

22 mins ago