Crisis of employment numbers

FACT Vs FICTION By B Sambamurthy All hell broke loose when the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a private think […]

FACT Vs FICTION

By B Sambamurthy

All hell broke loose when the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a private think tank, published the unemployment number at 8.2%. There was the usual slugfest between the economists on both sides of the spectrum. One section dismissed this number as inaccurate and not representative, while the other raised red flags and termed this as a serious job crisis.

8% unemployment does not mean 92% of the population representing nearly one billion people are gainfully employed and are having a good life

On an impulse, I thought that employment of 92% is a good enough number for an emerging economy like India. I wondered why this ruckus on job crisis. I then bumped into a friend of mine who is a Labour economist and asked him what is this hullabaloo and red flags when over 92% are employed in a huge country like ours with over 130 crore population. In a sermonic tone, he said that 8% unemployment does not mean 92% of the population representing nearly one billion people are gainfully employed and having a good life.

Rag Pickers, People Hawking at Traffic, Odd Boy Working at Chai shop

Moderating, if not dampening, my excitement, my Labour economist friend clarified that rag pickers are also counted as employed and so also people hawking at traffic lights, the boys and girls at chai shops doing odd things, etc. Persons who work even for one hour in a week or one day in a week are also counted as employed. Over 80% of the labour force works in the informal sector and these survey/estimation exercises become that much more arbitrary or harder.

Surveys but not Census

He cautioned that these are surveys and not census. The sample size of these surveys is based on less than 1% of the workforce. There are other issues like disguised employment, seasonal employment, frictional unemployment, transitory unemployment, structural unemployment, and gender skew in favour of males. The last census was done in 2011.

A lot of dividend from the massive 900 million people in the working age bracket lies on the table ill-consumed

As an explainer, he said that I should know some key employment indicators before I start knowing and understanding the employment numbers. In a lecture mode, he started the following discourse:

- Working Age

This population tells us the number of people in the working age, ie, above 15 years of age. It means a massive 900 million people in this country are in the working-age bracket. For a perspective, the entire European Union has a working age population of about 330 million. A massive demographic advantage we have been touting over the last two decades. A lot of this dividend lies on the table ill-consumed.

- Labour Force

Labour Force (LF) represents persons who are aged 15 years. It includes both employed and unemployed looking for and seeking work. More the number of these people, the higher the contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP). This is estimated at 530 million. There are segments like students, housewives and some who have lost hope of getting a job, etc., not looking for work and hence outside the labour force.

- Labour Force Participation Rate

This is the most important Labour market indicator to watch. This ratio tells us what proportion of the working-age population (over 900 million) are working or seeking and looking for work. This ratio, according to the CMIE, has been on the decline from nearly 47% about 6 years ago to 40% now.

The fall in this ratio slows the GDP growth since fewer hands and minds contribute to the production of goods and services. This number gives a deeper insight and the degree of inclusiveness of growth. This predictive indicator is important, if not more, as glamorous and easily available high-frequency indicators.

- Unemployed Rate

Then he explained the definition of unemployed as those who are unemployed but are willing to work and looking for work. So, he clarified that those who are not willing to work and looking for work, though unemployed, are not counted as unemployed. Many in this category are a potent threat to social cohesion.

- Greater Labour Force

These people represent those who are employed plus unemployed but willing to work and actively (desperately) looking for work. Active/desperate is the operative word.

Twin and Conflicting Data Sources: PLFS/CMIE

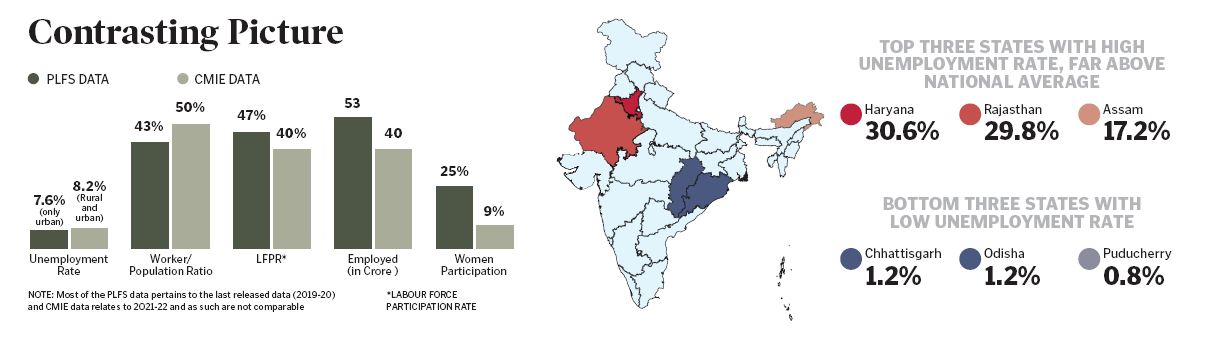

I set about looking for these data points. The government undertakes a survey, which is called Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). The CMIE is a well-known and hugely followed private agency which also does jobs survey called Consumer Pyramid Household Surveys (CHPS). But there are significant differences in the sample size, methodology and frequency of the exercise and hence their data output varies widely. (See Infographics: Contrasting Picture)

Defining Employed: One-hour, one-day work in a week Benchmark

The PLFS for its quarterly surveys considers a person as employed if the person works even for one hour in a week whereas CMIE’S yardstick is one-day employment in a week. Both these definitions of employment are bizarre if not immoral. These definitions fall much short of the ILO definition of “decent job”.

Variation among States

There are huge regional variations in the degree of unemployment. Some States fare badly and are way above the national average. The variation between the best and worst is abnormally high for comfort. (See: Top three, Bottom Three States)

This data is counterintuitive, to say the least. For example, the per capita GDP of Haryana is double that of Chhattisgarh. But the unemployment of Haryana is 25 times higher. Similarly, Haryana’s per capita is almost three times that of Uttar Pradesh, but its unemployment rate is nearly seven times that of UP.

The definitions of employment by both PLFS and CMIE are bizarre, if not immoral. They fall much short of ILO definition of “decent job”

Proxy Data: Insight by Half

The government has been taking steps to facilitate employment (particularly formalisation). There has been an increase in the number of people enrolled for the EPFO as well as the number of new companies registered. Data is also collected by Labour/Business bureaus. But these data points do not connect and, at best, one would get half insight. It is households which supply labour to businesses and for the government to produce goods and services. As such, household surveys provide actionable data.

Need to Improve Employment Statistics

Labour market data influences financial markets globally, particularly exchange rates, interest rates and even monetary policy. It is not just the CPI (Consumer Price Index) numbers alone.

“India’s rich digital footprint, rapidly advancing technology and ever-changing economy are shifting the expectations that policy makers and citizens have from the country’s statistical system,” says the World Bank. Incidentally, India availed $30 million loan from the World Bank in March 2020.

Economists/advisers may serve the country well by whispering truth and fact (not opinions) into the ears of the Prime Minister

Our statistical system needs to provide real-time inputs on the dynamics of the labour market for policymaking, including monetary policy and stronger disseminating practices. There is an urgent need to empower the National Statistical Commission and give it statutory backing. The draft Bill of 2019 draws from a 2011 report of the Madhava Menon committee.

The States have to take a far more active interest in surveys and remedial action.

Only those persons who work for at least three days a week must be categorised as employed. We also need to capture the numbers that meet the ILO definition.

There is an urgent need to empower the National Statistical Commission and give it statutory backing

It is said that data is the new oil. Our unemployment data is anything but new oil. This low-quality data is weaponised by political parties and being low quality, doesn’t hit the target. Many policy interventions would also end up as mere shots in the dark.

Economists/advisers may serve the country well by whispering truth and fact (not opinions) into the ears of the Prime Minister — Chanakya Neeti (paraphrased).

India’s problem is not just a lack of decent jobs but an equally important issue is the lack of reliable jobs data. We need to fix it.

[The author is former Chairman of National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) and senior banker]

Related News

-

AHSP of CCPT vehicle transferred at Ordnance Factory Medak

6 mins ago -

Residents to hold ‘Musi Dandi March’ against Gandhi Sarovar Project on March 1

16 mins ago -

Andhra CM slams YSRCP over Tirupati laddu adulteration

25 mins ago -

NH-65 accident: 20 passengers injured as three buses and car collide at Rudraram

31 mins ago -

Telangana govt allots 3.95 acres to HMWSSB for Kokapet–Neopolis water infrastructure

46 mins ago -

FTCCI hosts ‘Resilient Minds – Thriving Businesses’ workshop for entrepreneurs

55 mins ago -

Indian Embassies in Gulf, Iran issue safety advisories amid regional crisis

1 hour ago -

TiE Hyderabad launches 7th edition of TiE Women 2026

1 hour ago