No Apocalypse, Not Now

If it is a true Apocalypse or a complete extinction event, there would be no one left to write the tale

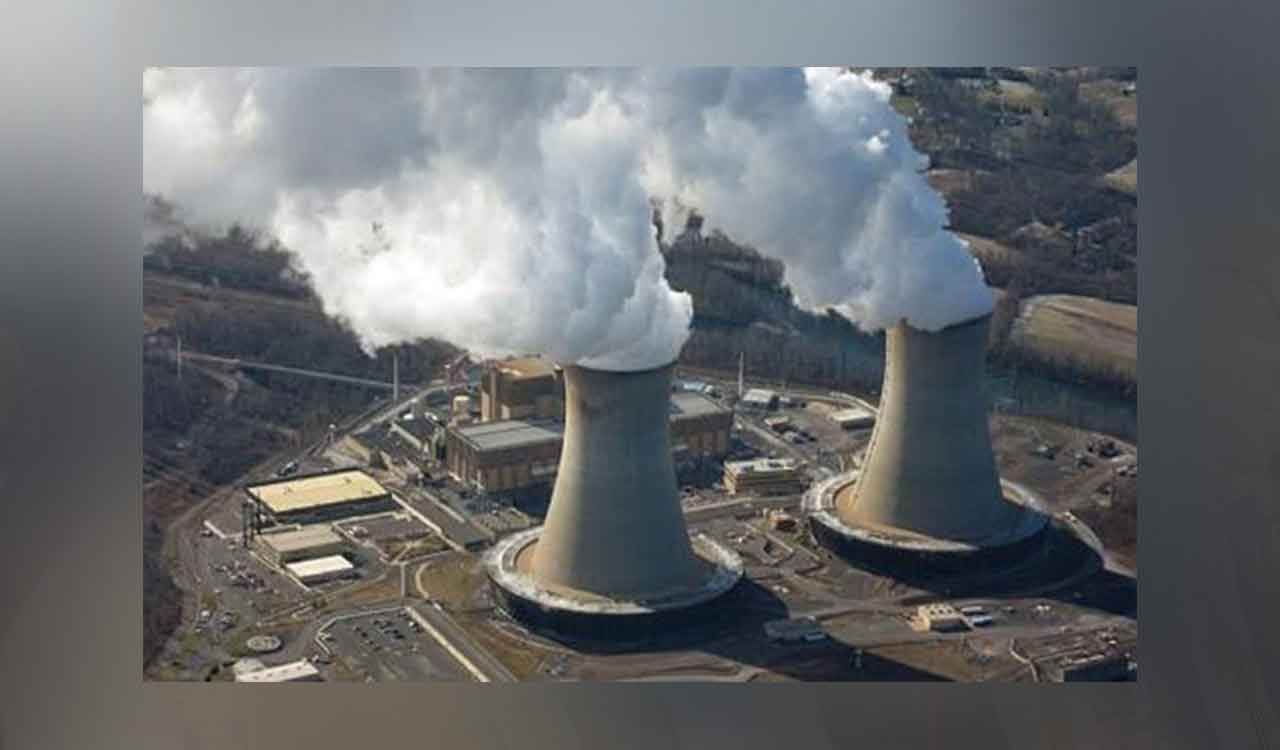

Dystopian films and pop cultural texts, whether 2012 or After Earth, imagine an Apocalypse, the end of humanity (or a few straggling survivors) and ecological disaster. In most cases, as scholars have argued, the Apocalypse, particularly the ecological one, has its roots in humanity’s cultural practices – from deep sea mining to dams, from deforestation to nuclear technologies.

The rise of the ocean levels, frighteningly sketched in texts like JG Ballard’s The Drowned World, Maggie Gee’s The Flood and others, promise death-by-drowning. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts a rise of 4 millimetre in mean sea level (MSL) by the end of the 21st century and commentators predict that even a 5 degree increase in global temperatures will mean an increase of 25 millimetre in MSL, and many of the coastal areas across the planet would disappear then.

Memories of the tsunami are not yet faded, neither is the Fukushima disaster following the 2011 tsunami.

Languages of Apocalypse

The standard language of the Apocalyptic in literature veers between the personal-subjective and the collective mourning account.

In Wave: A Memoir of Life after the Tsunami (2013), Sonali Deraniyagala who loses her entire family to the waters in Sri Lanka, uses the language of biology but cast in the language of personal loss: “All that while I’d told myself that they’d disappeared into the depths of the ocean. Vanished. Magically became extinct.”

In other texts, it is collective mourning. James Bradley’s Clade describes a drowned world and cities where in some places apartments rise above the water. In Wu Ming-Yi’s The Man with the Compound Eyes, the island Wayo Wayo is completely wiped out by the tsunami: “Everything on the island—the houses, the shell walls, the talawaka, the beautiful eyes, the woeful calluses, the salt-heavy hair, and all the stories about the sea—was consigned to oblivion in a heartbeat.”

The coast of Taiwan is altered by the Trash Vortex, an island of garbage that resembles the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which comes floating across the ocean and slams into it. The island’s key road is drowned by the Pacific: “As if the ocean is where they’d taken the road to get to, the band of travelers stood and gazed out across the vast Pacific at a listless sunrise, at the end of the road.”

Another commonplace of Apocalyptic language is the link forged between The End and violence. In Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, a novel both noir-thriller and eco-dystopia, the rivers of the USA have dried up and battles rage between the various states and their militia over the control of water. The violence and cultural collapse over water rights is insane, and described as Apocalyptic: “This was true apocalypse. The world after all the rules had stopped existing.”

The Apocalyptic is presented often as a one-time extinction event that wipes out the earth.

Before Apocalypse

While all the above dystopian texts envision The End, the prediction and the language of describing the extinction are quite inaccurate, argue many scholars.

Kyle Powys Whyte (2018), an indigenous scholar, argues that one cannot delink disastrous climate changes of the 21st century from a specific history – colonialism: “Indigenous peoples challenge linear narratives of dreadful futures of climate destabilization with their own accounts of history that highlight the reality of constant change and emphasize colonialism’s role in environmental change.”

A scholar who has done field work with the Inuit, and whom Whyte quotes, Candis Callison in her How Climate Change Comes to Matter: The Communal Life of Facts (2014) puts it baldly, asking us to consider what “climate change portends for those who have endured a century of immense cultural, political and environmental changes.”

Joe Sacco’s Paying the Land examines how mega-corporations mining for resources have ruined the land for the Dene peoples of the Canadian Northwest. The above instances and commentaries point to specific trajectories in climate change.

A Slow Apocalypse

First, colonialism, perhaps dateable to the 14th century, ravaged the land in terms of resources from various regions of the Global South. This altered the land irrevocably in racialised terms, ripping it apart and dividing it between the ‘natives’ and the European settlers, conquerors and traders.

Second, in cases across the planet, the displacement of the native inhabitants, ghettoising them, destroying their cultural practices, modifying lifestyles, and such produced a loss that was, again, irrevocable.

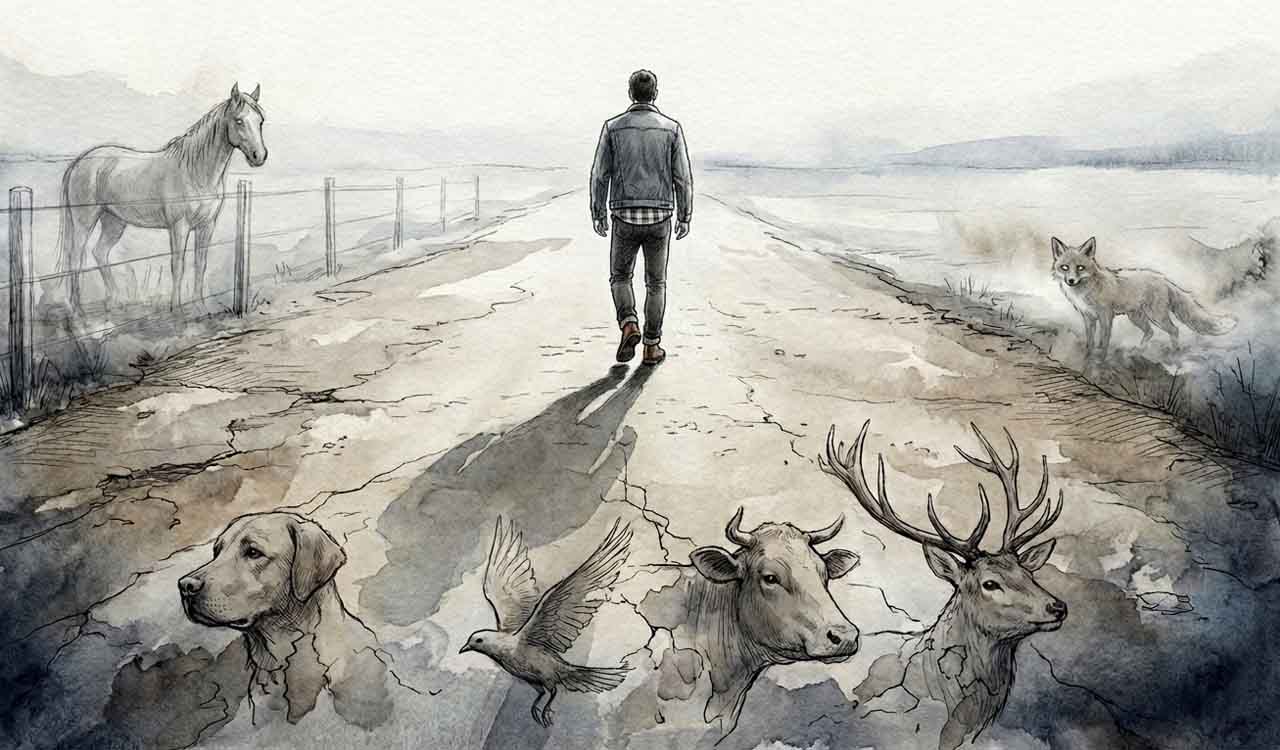

Third, well before this historical moment of colonial conquest was the human hegemony over the land from the beginning of the agricultural era, and the effect it had on other forms of life, on geology and the oceans. Again, these changes have been irreversible despite conservation attempts since the latter half of the 20th century.

What we see from these very abbreviated accounts is that there is no extinction-event for the most part. Most life forms, cultural practices and people have already encountered their Apocalypse in one of the three forms listed above. Their worlds have ended, and life forms disappeared.

The Apocalypse then is differential, affecting segments of the world. It is incremental, a slow Apocalypse, proceeding in stages to exterminate species, races, groups, cultures. That is, instead of visualising one massive end-of-the-world scenario – the Apocalypse – it is perhaps necessary to think of Apocalypse-Lite, an Apocalypse that creeps in across the planet, bit by inexorable bit. Maybe the Apocalypse-Lites are what we should worry about.

Logically, the single event that wipes out humanity is only a fable, as the philosopher Jacques Derrida argued in his 1984 essay which gives the title for this piece. It is a fable because it can only be fantasised as occurring in the future. For, if it is a true Apocalypse or a complete (human) extinction event, there would be no one left to write the tale. A true Apocalypse would be an event without a witness.

(The author is Professor, Department of English, University of Hyderabad)

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

Jadcherla hospital suspension row: TGGDA defends staff, demand infrastructure fix

3 seconds ago -

Four finance company staff from Mancherial stranded in Dubai, families express concern

34 mins ago -

SpiceJet to operate 8 flights from UAE

38 mins ago -

West Asia crisis: MEA establishes control room to assist Indians

42 mins ago -

Car falls into farm well in Nirmal, fertiliser company manager dies

50 mins ago -

Balka Suman alleges he was subjected to harassment in Adilabad jail

57 mins ago -

Army opens fire after suspicious movement along LoC in J&K’s Rajouri

1 hour ago -

Yash’s ‘Toxic’ postponed to June 4, averts clash with ‘Dhurandhar’

1 hour ago