Opinion: India’s Neighbourhood Dilemma

Even as India’s global and regional aspirations rise in the Indo-Pacific and the Global South, its near abroad needs renewed focus for the sake of its own interests and regional stability at large

By Monish Tourangbam

As the curtains came down on 2024 and the winter cold descended on India’s capital, the new Sri Lankan leader, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, came with a renewed promise of warmth in India-Sri Lanka relations. This will soon be followed in the New Year, with the Sri Lankan President setting foot on China, to engage with yet another crucial partner in Colombo’s politics, security and economics. This duality or rather the practice of autonomy among India’s neighbours has become an operational challenge for New Delhi’s foreign policy in its immediate neighbourhood.

Also Read

While the case of China-Pakistan nexus is more categorically detrimental to India’s interest in the region, other neighbours exhibit complex behaviours of geopolitics and geo-economics requiring more dexterity for New Delhi to deal with. Moreover, extra-regional powers like the United States may be distant in geography but not in strategy. Post its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the US has a freer hand to play in South Asia, which calls for honest dialogue between New Delhi and Washington. Therefore, even as India’s global and regional aspirations rise in the Indo-Pacific and the Global South, its near abroad needs renewed focus for the sake of its own interests and for regional stability at large.

Arc of Influence

India’s arc of influence abroad has certainly gained ground beyond any iota of doubt, and its voices from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Foreign Minister S Jaishankar are not only being heard but consulted on major questions of war and peace in the international system. No doubt, in purely material terms of economic and military indices, the United States and China stand apart from most other countries, but it is also equally true that in today’s growing multipolar world, solutions to major global problems cannot ignore the role of India.

Despite the lack of an immediate outcome, Modi’s welcomed visits to both Moscow and Kyiv show India’s ability to, at least, provide a bridge in a deeply divided world. Major issues of global concern from the regional conflicts in Ukraine and West Asia to climate change and financial restructuring, multilateral platforms like the G20, BRICS and COP29 cannot hope to become relevant without India’s input and active participation.

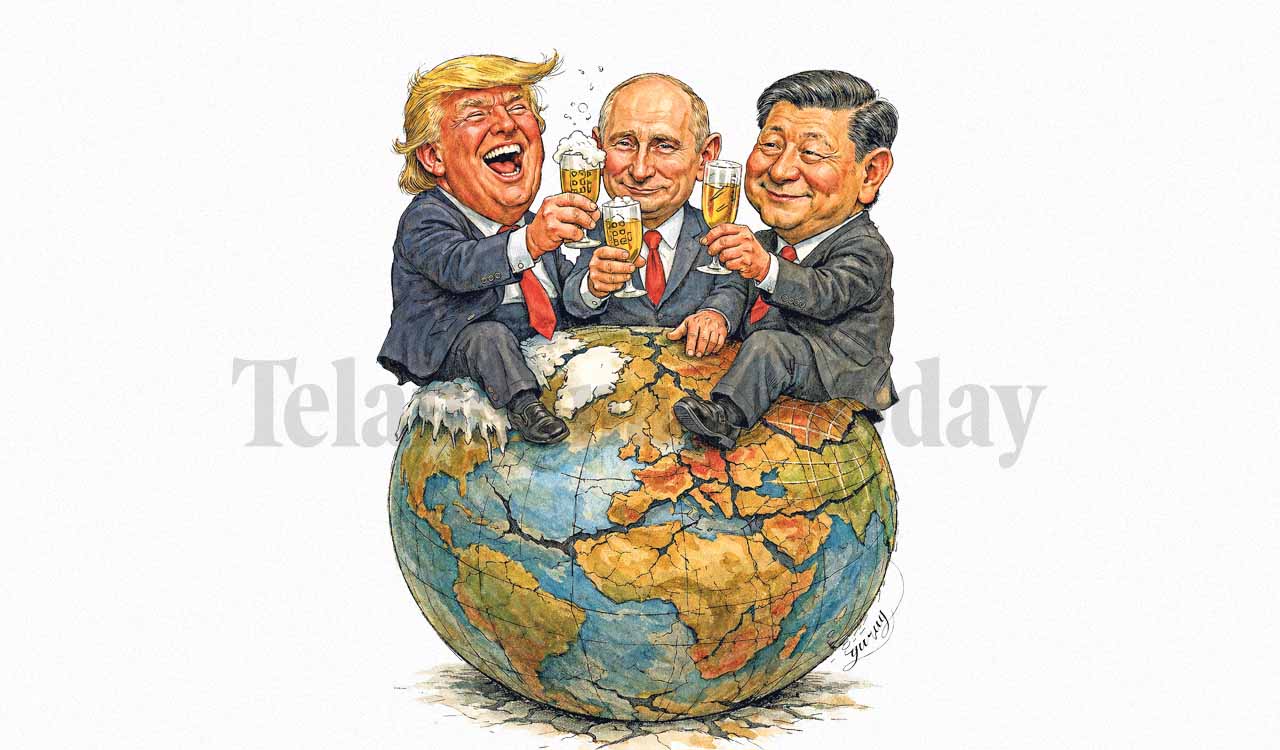

The growing animosity between the US and Russia, the growing rivalry between the US and China, and the rising alliance between China and Russia are pushing the world to a West and anti-West divide. However, New Delhi, at least, makes an effort to project the views of a non-West world that is not an antagonist to the West, thus representing the views of much of the Global South spreading across Asia, Latin America and Africa.

The new focus and discourse on the Global South, which got much-needed limelight during India’s G20 presidency last year, is thirsty for growth and development. They need aid and assistance to weather the storms of the new technological tides and the energy transition underway, and this is where the West or the Non-West, the Global North or the Global North needs to focus their efforts. Amid global supply chain disruptions and the shifts in how countries, big and small, adapt to them, India has the tall task of rising to the expectations of becoming a leading global power, while responding to the challenges nearest to home, which are the core of its security and economic interests.

Peril in Near Abroad

The chaos and drama of the regime change unfolding in neighbouring Bangladesh pose a clear and present danger to Indian foreign policy as the year comes to an end, before the dawn of a new year with new challenges and opportunities. That New Delhi enjoyed a close working relationship with the previous regime is a fact of the bilateral relationship, but the lesson of the current crisis is for India to remain ahead of the curve as far as its immediate neighbourhood is concerned, and objectively adapt to the fast-changing lanes of South Asian geopolitics.

Myanmar, though not technically a South Asian country, is one of India’s most important neighbours, and the ongoing civil war there, has immediate medium and long-term implications for what transpires in India’s north-eastern region, and most particularly now in the inferno engulfing Manipur for more than a year.

Creating convergences with like-minded partners and translating them to cooperation in the neighbourhood is the most viable alternative

Moreover, India’s most famed connectivity and infrastructure projects envisioned through its Act East policy such as the International Trilateral Highway and the Kaladan Multimodal Project are inextricably linked to political stability in neighbouring Myanmar, and the protracted uncertainties in the sub-region have put aspirations on hold. The multiple stakeholders in Myanmar, including the military regime, the National Unity Government and a diverse set of ethnic militias, all opposed to the current military rulers, but each carrying their own set of political end goals, complicate matters for India and the sub-region traversing the shared security-economic space of South-Southeast Asia.

Although there is a new turn of leaf in India-Maldives ties, with President Mohamed Muizzu having come on a long reconciliatory trip to New Delhi, after an intense phase of the ‘India Out’ campaign, the challenge of lending more predictability to India’s ties with its neighbours still lurks in the corner.

The case of Nepal remains an intriguing one. Like most South Asian neighbours, its political, economic, cultural and people-to-people ties with India are incomparable to its relationship with any other external power, including China, which undoubtedly has become a major development and security partner for India’s neighbours in continental South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. For instance, Kathmandu recently stepped up to sign its framework agreement with China to move forward on cooperation to implement the latter’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects in Nepal.

India’s dilemma in the neighbourhood is a case of the twin asymmetry problem. India’s smaller neighbours encounter an asymmetry vis-à-vis India’s geographical size and its political, cultural and economic influence. Simultaneously, New Delhi also faces the challenge of dealing with the asymmetry that exists between itself and China’s ability to provide material benefits to South Asian countries that desire developmental and security assistance.

How does India get out of this straitjacket? Creating convergences with like-minded partners and translating them to cooperation in the neighbourhood is the most viable alternative. Therefore, New Delhi needs to step up honest talks with its strategic partners to find more strategic congruence and prevent misalignment in priorities that end up hurting India’s core national interest in its neighbourhood.

(The author is the Director, Kalinga Institute of Indo-Pacific Studies [KIIPS])

Related News

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

33 mins ago -

SJFI national convention returns to Delhi with Hero MotoCorp as title sponsor

34 mins ago -

Delhi beats Hyderabad by nine wickets in BCCI women’s under-23 one-day championship

37 mins ago -

Hyderabad player Sowmith Reddy wins Unrated Chess Tournament at A2H Chess Academy

39 mins ago -

Editorial: T20 World Cup glory— rise of the Blue Tide

44 mins ago -

HC clears Ram Rahim in murder case, says CBI acted under pressure

1 hour ago -

Nampally court dismisses Sakala Janula Samme case against KCR, KTR

2 hours ago -

Bhoodan land row: 43 booked for violent protests in Khammam

2 hours ago