Opinion: India’s quiet demographic shift—Are we ready for it?

While maternal and child health indicators show remarkable progress, ageing populations, migration, and ‘ghost villages’ are a cause for concern

By Shreeji Anand, Raihan Sadath, Dr Maya K

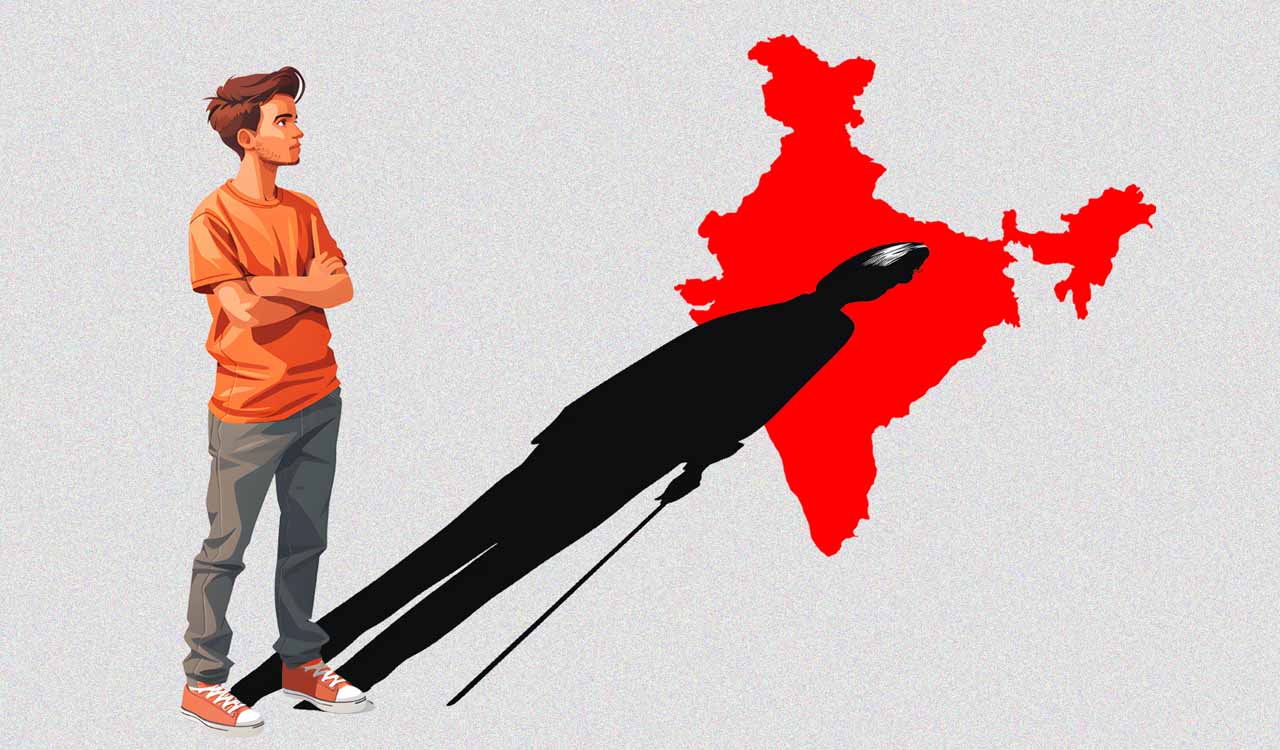

India stands at a pivotal demographic phase of transition. Amid global headlines celebrating its status as the world’s most populous nation, with an estimated 146 crore people, a quieter, yet profoundly significant, shift is underway. According to a report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), India’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR) — the average number of children expected per woman — has fallen to 1.9, below the replacement level of 2.1. This makes it imperative for the country to redefine the quality and strength of its human capital now more than ever.

Also Read

India has achieved remarkable progress in maternal and child health. The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) dropped significantly by 37 points, from 130 per one lakh live births in 2014-16 to 93 in 2019-21, with eight States already meeting the Sustainable Development Goal 2030 target of an MMR below 70. According to the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-agency Group (UN-MMEIG) Report for 2000-2023, India’s MMR has decreased by 86 per cent over the past 33 years (1990-2023), far exceeding the global reduction rate of 48 per cent.

Demographic Narratives

Child mortality indicators have also improved significantly. The Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) declined from 39 per 1,000 live births in 2014 to 26 in 2022. India has achieved a 78 per cent decline in the under-five mortality rate (U5MR), surpassing the global average decline of 61 per cent. Additionally, neonatal mortality rate (NMR) declined by 70 per cent, compared with the global average of 54 per cent, and infant mortality rate (IMR) by 71 per cent, against the global reduction of 58 per cent during the same period.

There is an urgent need for upskilling and human capital investment to sustain long-term economic growth

Yet, the very success of fertility decline in some States presents an unforeseen statistical paradox. In 2022, India’s annual crude birth rate (live births per 1,000 people in the total population) was 19.1, a 3.05 per cent fall since 2019. A closer look reveals two distinct demographic narratives. States like Bihar continue to record a high crude birth rate (26.9), driving population growth. On the other hand, States such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Delhi are experiencing a rapid demographic transition, with their annual crude birth rates declining at twice the national average. Tamil Nadu’s current crude birth rate of 12.1 places it in a league with many developed nations that are already grappling with ageing populations and workforce shortages.

Economic Implications

These numbers may seem abstract, but they carry big consequences for India’s future. This is because the transition is coming even before the country has reached developed living conditions. In contrast, countries like Japan and Germany saw fertility decline after they achieved strong economic growth through better healthcare, education and living index.

While States with substantial declines in fertility rates and crude birth rates have achieved considerable progress in development indicators, their demographic transition is now pushing them towards population structures that resemble those of highly aged Western nations, albeit without the same levels of robust social security and elder care infrastructure.

This demographic shift carries major economic implications in the form of high costs in geriatrics, old-age healthcare systems, and pension disbursements, diverting funds from development activities towards sustaining an old-age population. Most States remain ill-prepared for this proliferating fiscal burden. Migration is also reshaping population dynamics: In Delhi and Maharashtra, migration has become a key driver of population growth. Delhi has the highest share of people who have moved in from outside its territory, highlighting how urban centres continue to attract workers from demographically younger States.

Rise of Ghost Village

The low fertility, coupled with significant out-migration of its youth for work and education abroad or in other Indian cities, has created a peculiar demographic anomaly, the phenomenon of ‘ghost villages’ or ‘elderly villages’. A report by the BBC on Kumbanad, a town in Kerala’s Pathanamthitta district, illustrates this. Once home to 700 schoolchildren, it now has only 50 across all grades, primarily hailing from underprivileged sections. The entire infrastructure reveals a greying population, with few people residing in the town.

From an economic lens, this shift demands strategies and policies focused on upskilling, empowering, and targeted investments in strengthening human capital.

With Generation Z taking over as the working population, and the labour productivity declining in India, along with it being low compared to global standards (according to CEIC), there is an urgent need to address this pervasive concern. To secure long-term growth, the country must invest in upskilling and human capital to improve people’s knowledge, skills, and health.

(Shreeji Anand and Raihan Sadath are students of Third Year Undergraduate Economics, and Dr Maya K is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, CHRIST [Deemed to be University], Bengaluru)

Related News

-

FDDI introduces new UG, PG programmes across schools

3 hours ago -

Harish Rao to visit illegal quarry in Neopolis on Thursday

3 hours ago -

Holi celebrated with enthusiasm in Kothagudem, Warangal

3 hours ago -

BRS leaders come to the rescue of Velugumatla displaced families

3 hours ago -

Allen crushes South Africa dreams with record century, Kiwis storm into T20 World Cup final

3 hours ago -

Congress councillor disqualified in Isnapur Municipality for voting against party whip

3 hours ago -

KTR condemns civilian deaths following Israel-US bombing in Iran

3 hours ago -

Podu farmers clash with forest staff in Telangana’s Aswaraopet

3 hours ago