Opinion: India’s legal market liberalisation — From promise to protectionism

Bar Council of India’s evolving policy reveals more restrictions than reforms, diluting the intent of the 2023 foreign lawyer framework

By Divya Sridhar

What was initially heralded as a watershed moment for India’s legal landscape has proven to be a false dawn. In March 2023, the Bar Council of India (BCI) announced rules permitting foreign lawyers and law firms to practice in the country. However, subsequent press releases have revealed stiff resistance to foreign law firms, even when collaborating with local lawyers, effectively undermining the liberalisation that the original policy purported to introduce.

Also Read

The Bar Council of India’s Rules for Registration and Regulation of Foreign Lawyers and Foreign Law Firms were presented as a step towards opening India’s legal market to international competition, as the country positions itself to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030. Yet the gap between this promise and the reality of implementation has grown increasingly stark.

Restrictions Pile Upon Restrictions

Under the framework, foreign lawyers can practice in India only in non-litigious matters such as mergers and acquisitions, stock listings, contract drafting, and advisory work. They remain barred from appearing before Indian courts or regulatory authorities in disputes. Even in arbitration, supposedly the main area of liberalisation, the restrictions are severe. Foreign lawyers are not permitted to conduct the cross-examination of witnesses in India-seated arbitrations or in arbitrations involving Indian contracts.

Recent developments have cast doubt on even this limited opening. In October 2025, the Bar Council issued a press release prohibiting foreign lawyers from participating in arbitration proceedings where Indian law is the governing law, even in international commercial arbitrations conducted in India. It also limits the “fly-in fly-out” mechanism, which the Supreme Court had previously recognised for temporary consultations. This represents a notable retreat from what many interpreted as the original intent of the 2023 rules.

Adding to the confusion, a BCI press release dated August 5, 2025, was withdrawn following proceedings in Atul Sharma v. Bar Council of India before the Delhi High Court, highlighting significant regulatory uncertainty and inconsistency in the Bar Council’s position. “Opening up of law practice in India to foreign lawyers in the field of practice of foreign law” represents what the Bar Council characterises as a shift from its previous stance that law is “not a trade and briefs no merchandise.” Yet the gap between this rhetoric and ground reality grows wider with each new clarification.

Reciprocity — But Only With the UK

The rules include a reciprocity clause that currently extends only to the United Kingdom. This means foreign lawyers can practice in India only if their home jurisdiction allows Indian lawyers similar access. For now, only UK-qualified lawyers benefit from this arrangement, raising questions about when — or if — reciprocal arrangements with other major legal markets will materialise.

The nature of permitted operations also remains unclear. Can foreign law firms establish permanent offices in India, or are they limited to temporary fly-in, fly-out arrangements? This ambiguity creates further uncertainty for international firms considering Indian operations.

The rules address a longstanding imbalance in the legal profession. Senior Counsels like the late Fali Nariman, Harish Salve, Darius Khambatta, Gopal Subramaniam, and Arvind Datar have gained recognition and practised in foreign jurisdictions. Yet, similar opportunities for foreign lawyers in India have been virtually non-existent, and the new rules do little to change this reality.

Economic Case and Its Limitations

The economic rationale for liberalisation appears compelling on paper. India attracted USD 70.9 billion in foreign direct investment in 2022-23, in top sectors, including banking, insurance, technology, and telecommunications, where all highly regulated industries require sophisticated legal navigation. Foreign investors may find comfort in working with familiar international law firms operating in India, potentially encouraging greater investment flows.

The Indian legal sector itself experienced remarkable growth, expanding from an estimated Rs 33,412 crore in 2012-13 to over USD 1.3 billion today, making it one of the country’s fastest-growing sectors. Proponents argue liberalisation will democratise legal work, spreading international casework across a broader section of the bar and potentially attracting Indian legal talent working abroad back home.

Regulatory uncertainty, arbitration limits, and protectionist impulses now threaten India’s competitiveness and undermine the policy’s original promise of legal market liberalisation

However, the October 2025 restrictions on arbitration practice are particularly counterproductive to these objectives. By barring foreign lawyers from arbitrations governed by Indian law, even those involving international parties, the BCI has undermined India’s competitiveness as an arbitration venue. International commercial arbitrations frequently involve questions of Indian law concerning contract performance, regulatory compliance, or investment treaties. Singapore, Hong Kong, and London allow parties to engage counsel of their choice regardless of governing law, making them more attractive forums.

Legitimate Concerns

Critics worry that opening the market to foreign firms will exacerbate existing problems in an already strained legal sector with low demand and oversupply of lawyers. The plight of junior lawyers facing long hours and inadequate compensation despite rising costs of living remains a persistent concern.

Currently, only about one in every 1,000 Indians is a lawyer, leaving each lawyer competing for fees from approximately USD 1.4 million of GDP. At the same time, the Indian legal market faces an oversupply of professionals, with many lawyers chasing too few high-value opportunities. The fear is that foreign competition will leave many struggling to survive in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

The Indian legal market, like others globally, is dominated by a handful of major law firms, with corporate transactional work often restricted to graduates from elite institutions. This leaves litigation as the primary option for many lawyers, a field already struggling with economic viability.

The BCI’s response, progressively restricting foreign lawyers’ scope rather than addressing domestic structural problems, risks throwing away potential benefits while failing to solve the underlying issues affecting Indian lawyers’ welfare.

Missed Opportunities

The rules emerged from years of legal controversy, culminating in the Supreme Court’s 2018 judgment in Bar Council of India v. AK Balaji. That decision left the door open for the BCI to frame appropriate regulations for international commercial arbitration.

The regulatory instability exemplified by the withdrawal of the August 2025 press release following Atul Sharma v BCI proceedings in the Delhi High Court compounds the problem. International law firms require predictability before committing resources to establishing Indian operations. The current environment suggests that even limited permissions granted today might be withdrawn tomorrow.

This retreat appears driven more by protectionist impulses than coherent policy objectives. While protecting Indian lawyers’ interests is within the BCI’s mandate, overly restrictive rules harm the profession by limiting exposure to sophisticated international work and preventing Indian lawyers from competing globally.

Since the early 2000s, Indian law firms have been preparing for liberalisation through “best friends” agreements and non-exclusive referral arrangements with foreign firms. One UK firm reportedly encouraged partners from two Indian firms to leave and create an entirely new entity to facilitate market entry. These preparations now seem premature given the restrictive trajectory of actual implementation.

The trajectory since March 2023 suggests missed opportunities. What was announced as a step toward integrating India into the global legal market has, through successive restrictions, become something far more limited. The gap between the policy’s stated objectives and its implementation threatens to leave India watching from the sidelines as other Asian jurisdictions capture the growth in international legal services and arbitration work that could have been India’s.

(The author is Assistant Professor, Jindal Global Law School, OP Jindal Global University)

Related News

-

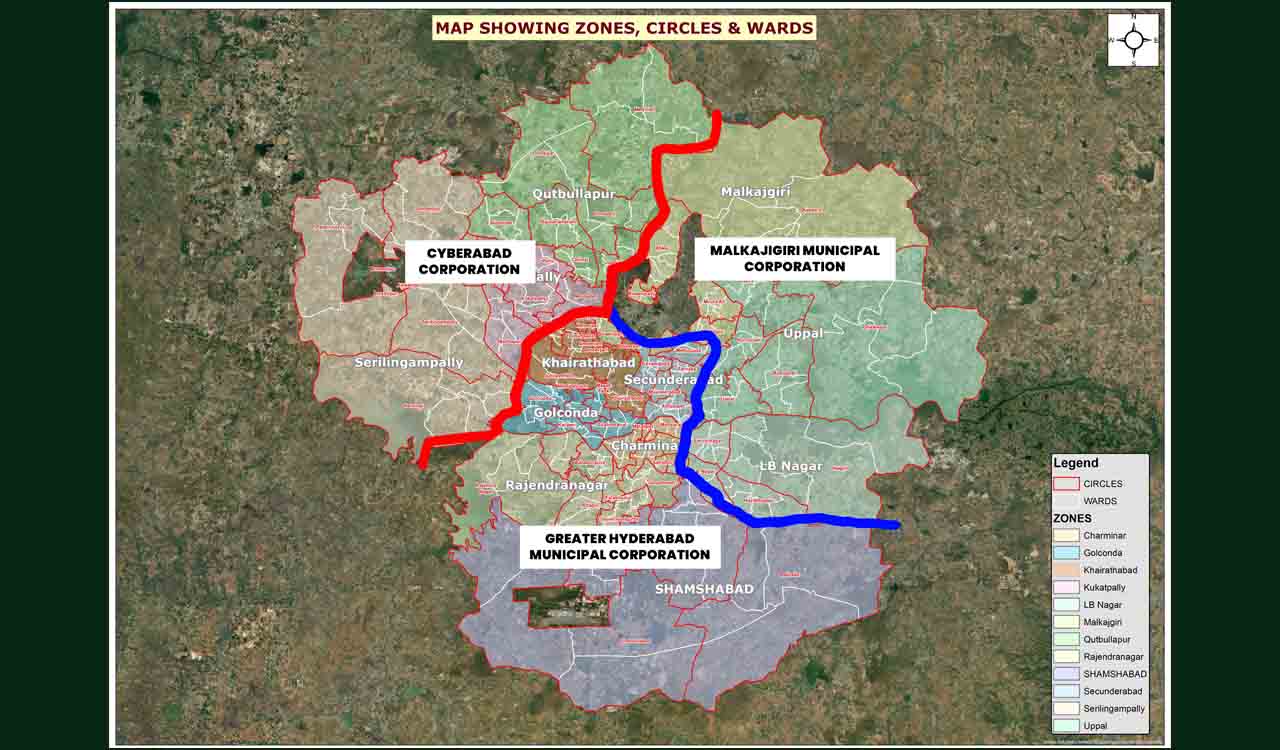

BJP shifts municipal poll candidates from Telangana to Maharashtra ahead of results

1 min ago -

Rupee jumps 38 paise to 90.40 on dollar amid inflows, RBI support

14 mins ago -

Students protest poor quality food at tribal welfare residential school in Narayankhed

16 mins ago -

Congress leader moves SEC against party MLA over poll malpractice

10 hours ago -

BRS seeks action against Jagga Reddy, flags counting day threat

10 hours ago -

High voter turnout recorded across 19 municipalities in erstwhile Medak district

10 hours ago -

Salman’s brother-in-law gets threat email; Bishnoi gang link suspected

11 hours ago -

BRS slams police inaction over alleged attack by Jagga Reddy

11 hours ago