Opinion: CBSE’s bold move — twice the opportunity

CBSE’s Biannual Exam Policy isn’t a luxury — in a country of 1.4 billion, with boundless diversity and dreams, a second chance is a necessity

By Chada Rekha Rao

When the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) recently announced its decision to introduce biannual board examinations for Classes 10 and 12, the reaction was predictably mixed. While students cheered and educators welcomed the choice-driven approach, some quarters — primarily armchair critics and status-quoists — rushed to label it a logistical nightmare. “Twice the exams? Impossible!” they cried. “Unmanageable,” they claimed.

Let’s pause. Breathe. And apply reason. Because here’s the truth: this reform is not a crisis — it is clarity. It is not chaos — it is compassion.

A Revolution That Was Long Overdue

For decades, India’s board examination system has been rooted in rigidity. One exam. One chance. One mistake? A year lost. The sheer emotional and psychological weight placed on a 16-year-old’s shoulders in February-March has caused anxiety spikes, sleepless nights, even breakdowns.

Enter biannual board exams — a landmark move by the CBSE aligned with the National Education Policy, 2020, which advocates for flexibility, choice, and learner-centric assessment. This reform brings Indian education closer to global standards, where students get multiple chances to demonstrate their learning, rather than being crucified for a single performance.

Not a Compulsion, But a Choice

Let’s be clear: biannual doesn’t mean twice the stress. Students aren’t being asked to take two exams compulsorily. They’re being given a choice — appear in both, or only once. If a student is satisfied with their February performance, they don’t need to appear in May. If they wish to improve, or couldn’t appear earlier due to unforeseen circumstances, May gives them a second chance. It is a safety net, not a burden. A ladder, not a whip.

Mental Health First: A Student-centric Perspective

This reform is as much about mental health as it is about academics. Every year, we witness tragic news of students succumbing to exam pressure. With just one attempt, the stakes become unbearably high. By splitting the pressure across two sessions students can pace their preparation better. They can experiment with strategies — attempt a few subjects in February, and the rest in May.

Performance anxiety is significantly reduced, knowing there’s another chance around the corner. The era of mugging up in fear must end. Biannual exams move us towards education through understanding, not memorisation under duress.

Global Best Practices

The biannual system is not new — just new to CBSE. Globally, most standardised tests adopt multiple cycles:

- SATs and ACTs (US) are held several times a year.

- Cambridge IGCSE and IB assessments offer flexible exam windows.

- Even India’s NEET and JEE-Main have moved to biannual formats, yielding excellent results.

If medical and engineering aspirants can manage two attempts a year, why can’t Class 10 and 12 students be trusted to do the same?

Logistics: Not a Nightmare

One of the biggest myths floated about this reform is that it’s logistically impossible. Let’s puncture that balloon.

Most CBSE schools are not exam centres: In a city like Hyderabad, there are approximately 259 CBSE schools, yet only a small percentage are used as board examination centres each year. This means we already have a reservoir of untapped capacity.

One of the silent victories of this reform is how it levels the playing field for economically disadvantaged students — they don’t need to pay for re-admission or repeat the entire year. A second chance requires time, effort, and access — which the CBSE will provide for free

So why not divide the load? February exams can use a designated set of schools. May exams can use a different set, including schools that were earlier exempted due to lack of infrastructure or staff. This system ensures rotation, fairness, and efficient utilisation of available space.

May exams will see fewer candidates: Since the February exam is mandatory, it will see maximum participation. May will only attract students aiming for improvement, those who couldn’t appear earlier due to illness or emergencies, and select subject-specific aspirants. This naturally reduces the logistical burden on May centres, allowing us to use smaller schools or those without full-fledged strongrooms.

We can use alternative infrastructure: India runs elections across deserts, forests, and islands using public buildings, police stations, and panchayat offices. Why can’t we repurpose the same for May exams?

- Banks with secure premises

- Community halls

- Unused college spaces

- State-run digital centres

With proper planning, May exams can run like a tightly managed mini-election. Schools often dread being turned into centres due to the disruption it causes. Now, with a two-cycle system, centres can be rotated, giving schools breathing space between years or cycles. Teacher burnout is reduced, and administration becomes more predictable.

Economic Equity and Accessibility

One of the silent victories of this reform is how it levels the playing field for economically disadvantaged students. Students who perform poorly in February don’t need to pay for re-admission or repeat the entire year. A second chance doesn’t require coaching. It only requires time, effort, and access — which the CBSE will now provide for free.

Dropout rates will fall, especially among rural and first-generation learners, where a failed board exam often means the end of education. In a society striving for equity, this is more than reform. It is redressal.

Course Corrections

Of course, no reform is without its teething problems. CBSE must:

- Release an academic calendar well in advance, including result declaration dates and re-evaluation deadlines.

- Ensure that college and university admission cycles align with this new structure.

- Provide teacher training and incentives for handling two exam sessions.

- Educate parents and schools about the purpose and process of biannual boards so that myths don’t fuel resistance.

The National Education Policy, 2020 made bold promises: flexibility in assessments, reduced rote learning, student choice and personalisation, and multiple pathways to success. The biannual board exam policy is a direct translation of these goals into action. We are finally walking the talk.

Courage Over Convenience

In a country of 1.4 billion, with boundless diversity, dreams, and determination, a second chance isn’t a luxury — it is a necessity. The CBSE’s biannual board examination reform doesn’t dilute academic rigour. It dignifies student effort. It doesn’t double stress. It divides pressure and multiplies hope.

Let’s stop seeing this as a logistical hurdle, and start seeing it for what it truly is — a democratic, student-first reform that allows young minds to rise not once, but twice. After all, education should be about building minds, not breaking spirits.

(The author is Principal of Oxford Grammar School, Hyderabad)

Related News

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Opinion: Lives in limbo — Myanmar and Manipur refugees in India’s northeast

-

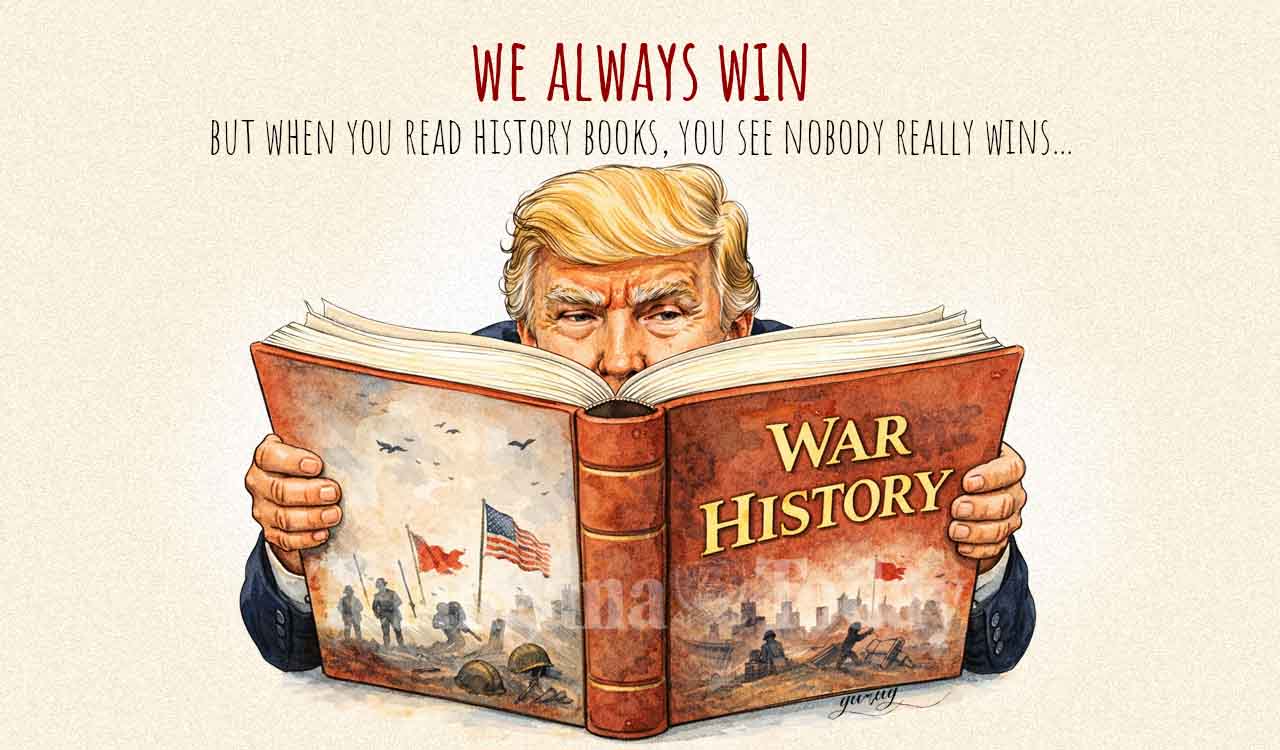

Opinion: US-Iran war — the cost of ignoring history

-

Ramagundam cybercrime police hold awareness programme for college students

2 mins ago -

Police resort to lathi charge at Tank Bund after India’s T-20 World Cup win celebrations

6 mins ago -

NRIs advise Indians to utilise Malaysia’s migrant repatriation programme

12 mins ago -

Sanju Samson emerges as Kerala’s new sporting icon after World Cup heroics

41 mins ago -

Cricket world praises India after historic third T20 World Cup title

48 mins ago -

Sri Lanka appoint Gary Kirsten as head coach ahead of 2027 ODI World Cup

59 mins ago -

Suryakumar Yadav eyes Olympic gold after India’s dominant T20 World Cup campaign

1 hour ago -

Cyclist Kanthi Dutt begins 800-km Hyderabad to Mumbai expedition to promote fitness

1 hour ago