Opinion: India’s ageing population—unpacking the overlooked dilemmas

Rethink ageing as a social developmental challenge to reap the demographic dividend

By Dr Anuradha PS

As India demographic dividend continued to be talked about in policy circles, a less talked about but an important transformation is occurring- India is ageing fast. The National Commission on Population predicts that the percentage of individuals 60 years and older is going to reach beyond the 20% mark in 2050, as compared to approximately 10.1 per cent in 2021. This demographic transformation has not only been a notice of better longevity but rather a complicated social, economic and policy issue, which has evaded the eyes of both populace and politics.

Also Read

The vulnerable position of the ageing population in India has various challenges. The Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI, 2017-18) presents dismal statistics; approximately one-fifth of older adults are on any kind of pension, and access to proper healthcare is a miscellaneous affair. The social changes that accompany these gaps are diminished joint family structures, an escalating urban migration trend, and the destruction of the traditional support systems.

Kerala Example

In Kerala, where the proportion of elderly individuals is rather high, perfection in health situations has led to an increase in life expectancy, despite the fact that most elderly persons experience loneliness, depression, and neglect due to the migration of younger relatives to other centres or foreign countries. Meanwhile, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, whose population is younger, but its health infrastructure is less well developed, older residents of rural areas are generally deprived of access to basic primary care and social services, which increases their vulnerability.

In Tamil Nadu, a relatively well-developed healthcare system has somehow been unable to counter the forces of rapid urbanisation, leading to a modified family structure and thus, to greater social isolation among the older members of the population. Access to affordable long-term care and mental health issues because of loneliness, as experienced by many older adults in Tamil Nadu, are the major challenges faced in their lives.

Urban Seniors at Risk

In Karnataka, particularly in the semi-urban or rural areas, it has been observed that the elderly population is faced with low accessibility to geriatric healthcare facilities as well as social security protection. Even though Bangalore and other urban centres provide superior health care services, increased living expenses and the collapse of the traditional family support system expose many urban seniors to risks. The allure of rural Karnataka is comparable to other less-developed areas that have poor health infrastructures and economic insecurity, which makes the ageing populations even more vulnerable.

The India Ageing Report 2023 by UNFPA lists the state of India as having a population size of about 149 million, aged 60 years or older, as of 1 July 2022, constituting 10.5 per cent of the total population, and which is expected to increase to 15 per cent by 2036 and to 20.8 per cent by 2050 (UNFPA, 2023; The Times of India, 2023). Another important theme represented in the report is the fact that the number of individuals aged 80 and above will rise by 279 per cent between 2022 and 2050, as well as the presence of massive inter-state disparities, with the states of Kerala, Himachal Pradesh, and Punjab already having higher shares of the elderly than the national average (UNFPA, 2023).

Urban-based programmes are unable to meet the challenges of geriatric patients in rural and tribal regions because of their multidimensional needs

Moreover, in 2021, the ratio of dependency of older adults in India was approximately 16 older individuals per 100 working-age people, and more than 40 per cent of this group are in the poorest wealth quintile, and almost 18.7 per cent of them have no income (UNFPA, 2023; The Times of India, 2023). According to the statistics given in Sample Registration System,2023, the current stage of the Indian population is 9.7 percent aged 60, 6.4 percent aged 65, and the states that have the highest proportion of elderly citizens are Kerala (15.1%), Tamil Nadu (14%), Himachal Pradesh (13.2%) and Punjab (11.6%) (Business Standard, 2023; The Indian Express, 2023). A 2025 report by NHRC also reports increased social isolation, with 18.7 per cent of the elderly women and 5.1 per cent of the elderly men living alone and almost 70 per cent of older people being financially independent (NHRC, 2025). To further elaborate on these statistics, NITI Aayog estimates that the older population is expected to increase to 319 million (which is 19.5%) in 2050 (NITI Aayog, 2024).

Policy-based solutions like the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS) and the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) are a significant step forward, but are not adequate in extent and coverage. Providing pension coverage is uneven, with the greatest number of the old being the informal sector workers who are not covered. Urban-based and underfunded healthcare programmes are unable to meet the challenges of geriatric patients in rural and tribal regions because of their multidimensional needs.

Capability Approach

In order to comprehend the experience of ageing in India, we should resort to the capability approach introduced by Amartya Sen that draws our attention to real liberties and opportunities that older people experience today, rather than their simple survival. Ageing is not merely a biological reality depending upon the biological determinants, but it is the result of socio-economic status, gender, caste and geography; some of them strengthen or inhibit a person from leading a full and dignified life.

Moreover, the life course perspective suggests that the outcomes of ageing are cumulative since they depend on the conditions of life till this moment. It makes it apparent that a comprehensive approach to policy is necessary to encompass the full range, including access to healthcare and financial security, social integration and mental well-being.

Policy adjustment is the need of the hour. Initially, pension programmes should be extended to informal workers by streamlining the registration and delivery process and making sufficient budgetary provisions. Second, geriatric care needs to be incorporated into the National Health Mission, focusing more on community outreach and mobile health services. Third, isolation and marginalisation can be reduced through investments in the provision of elder-friendly urbanisation, easy access to the community, and social engagement activities.

Location-specific Strategies

Lastly, given the existential heterogeneousness in the ways that people experience ageing, decentralised governance and local community responses should be strengthened to come up with culturally safe and location-specific elder care strategies. Social clubs, community kitchens and a day-care centre may be very important in supporting elder dignity and agency.

Based on the experiences of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Aging (KLoSA), the Japanese Study of Aging and Retirement (JSTAR) and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), India should establish an ageing research infrastructure and immediately implement evidence-based, inclusive, and rights-based policy. These analyses show that with sound data gathering, any significant welfare reforms can succeed in making the lives of the aged more positive and their approach more dignified. India can fulfil its ageing population and prevent the social crisis that is about to happen if the country mimics the approaches of other countries that have been addressing the ageing issue in the same way, working out the multifaceted challenges of the ageing population.

It is unwise to neglect the demands of older people in India today because of the enhancement of social inequalities within India tomorrow. Unless ageing is rethought as a social developmental challenge, and not the individual duty, the demographic dividend will turn into a demographic challenge. India needs to evolve out of token welfare schemes to include rights-based policy frameworks; it is a moral and economic necessity for the future of India.

(The author is Professor, Department of Commerce, CHRIST [Deemed to be University])

Related News

-

Jamiat calls Centre’s Vande Mataram order arbitrary and unilateral

1 min ago -

CPI-M MP A A Rahim flags stress and suicides in public sector banks

9 mins ago -

Nishikant Dubey seeks action against Rahul Gandhi through substantive motion

15 mins ago -

Telangana State United Teachers’ Federation demand reduction of TET qualifying marks

17 mins ago -

Former Doordarshan news reader Sarla Maheshwari dies at 71

22 mins ago -

Amit Shah to attend Akhil Bharatiya Rajbhasha Sammelan in Tripura

29 mins ago -

KGMU professor suspended over sexual harassment complaint by MD student

36 mins ago -

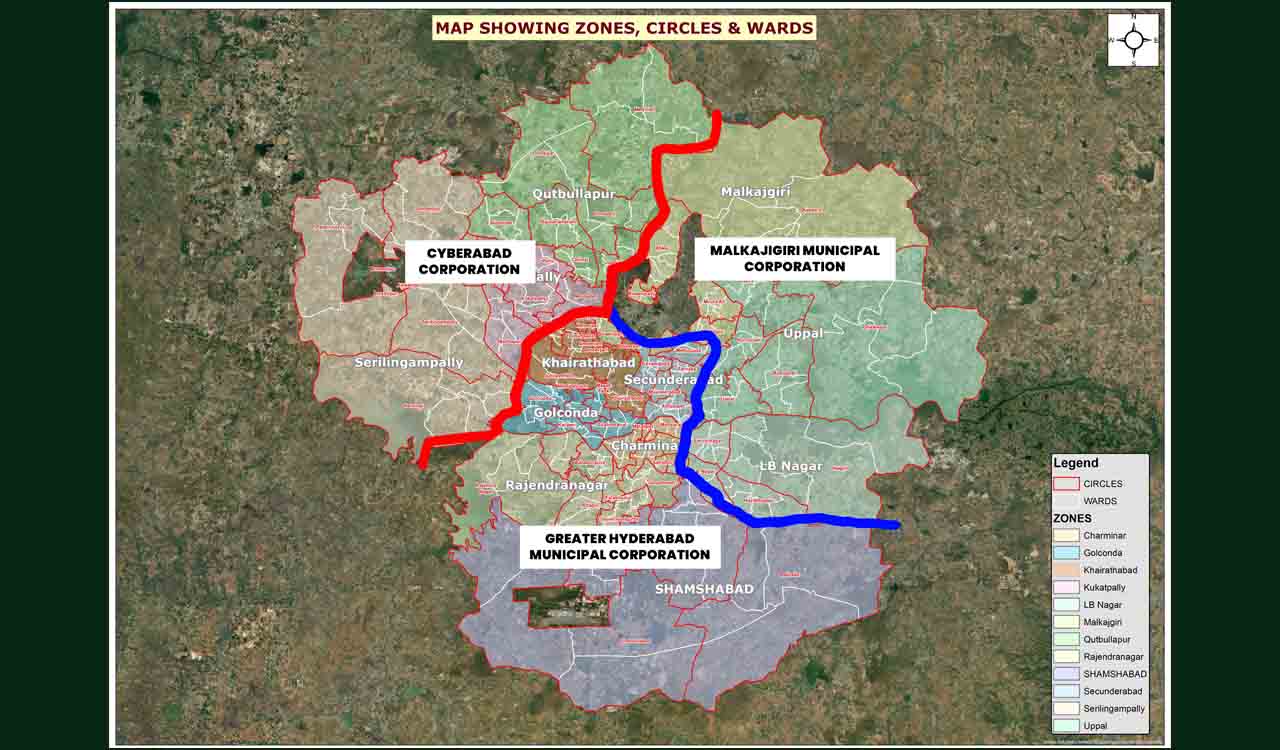

GHMC trifurcation: Standing Committee allots Rs 500 crore to MMC and CMC

42 mins ago