Opinion: Electoral Roll Revision: Cleanup or calculated move?

As the BJP replays Assam agitation on a national scale, one must ask: Is this really about national security, or just another chapter in the politics of manufactured threats?

By Geetartha Pathak

The Election Commission of India has announced that, following the voter list scrutiny in Bihar, a nationwide review will now be undertaken. The reasoning provided is a familiar one: to identify and remove names of foreign nationals, particularly those suspected to be from Bangladesh, Nepal, or Myanmar.

The ruling BJP, in turn, has accused opposition parties — especially the Congress and the Left — of encouraging such inclusions in the voter rolls for political gain. The opposition, on the other hand, views this drive as a thinly veiled attempt to suppress their support base and further polarise society.

Special Intensive Revision

The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar began on June 25, with Booth Level Officers (BLOs) tasked with collecting Enumeration Forms from voters by July 25. A draft electoral roll is scheduled for release on August 1, followed by a claims and objections period. The ECI has specified 11 acceptable documents for voter verification, explicitly excluding Aadhaar, Electors Photo Identity Card (EPIC), and ration cards.

However, in response to petitions challenging the SIR, the Supreme Court, on July 10, urged the ECI to consider including these documents as valid proofs. The court’s final ruling is expected on July 28, just days before the draft list’s publication, leaving the process in a state of uncertainty.

The exclusion of widely held documents like Aadhaar and ration cards has raised eyebrows, particularly as these are commonly used for identity verification across India. Critics argue that the ECI’s restrictive approach could disproportionately affect marginalised communities, who may lack access to the specified documents.

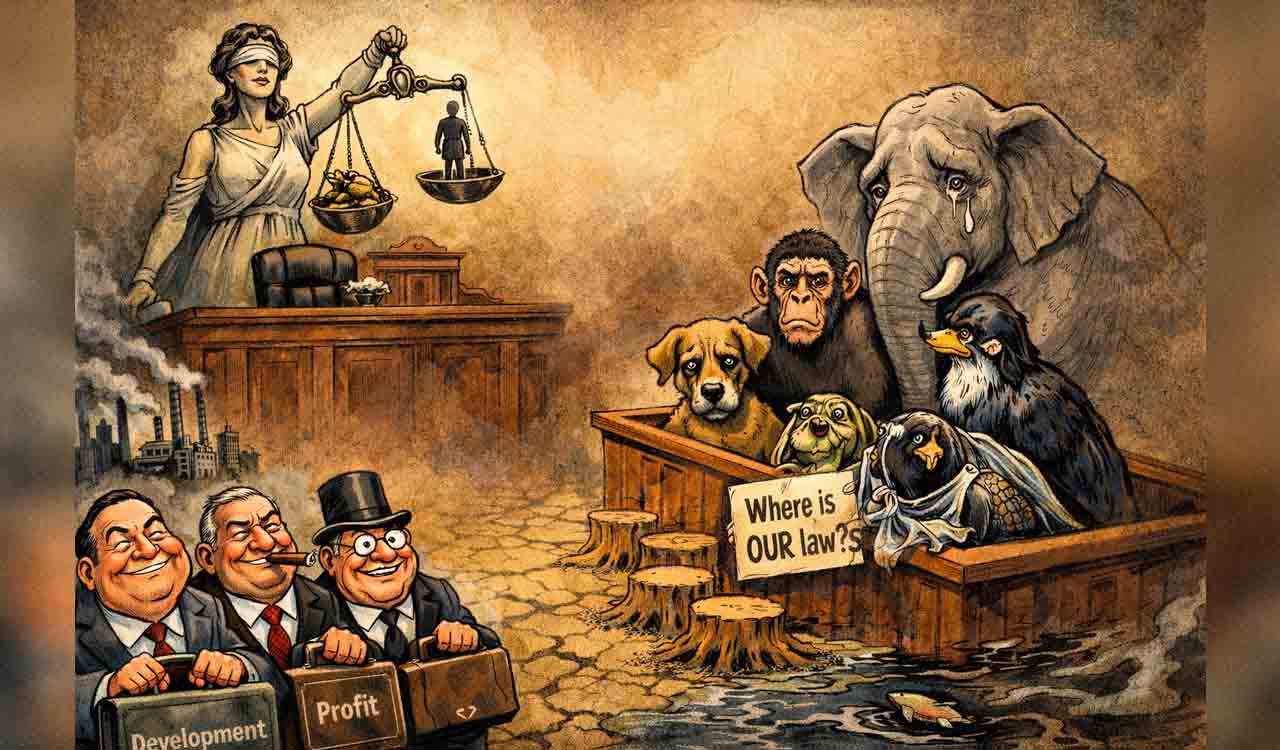

The Supreme Court’s suggestion to include Aadhaar and ration cards reflects this concern, though the court also noted that the ECI retains the authority to reject any document deemed insufficient. The SIR in Bihar, now extended nationwide, seems to be another step in this long political saga. Officially aimed at “cleansing” voter rolls, it risks becoming a tool for voter suppression and political polarisation. Without legal authority to determine citizenship, the EC’s actions could unjustly strip legitimate citizens of their voting rights.

Assam Revisited

This narrative is not new. In fact, it harks back to the tumultuous events of 1979 in Assam during the Mangaldoi parliamentary by-election. Allegations then arose that a large number of foreign nationals — mainly from Bangladesh — had been registered as voters. This claim triggered the historic Assam Agitation, led by the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), demanding the identification and deportation of illegal immigrants.

The AASU insisted on a cut-off year of 1950 for accepting any migrants from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). After six years of widespread protests, violence, and negotiations, the Assam Accord was signed in 1985, laying down a legal framework for identifying foreign nationals in the State and setting March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date for citizenship.

However, the real challenge began after the Accord. The AASU and others pushed for effective legal mechanisms such as the repeal of the IMDT (Illegal Migrants Determination by Tribunal) Act, which they claimed hindered the detection of illegal immigrants. The Supreme Court struck down the IMDT Act in 2005, terming it unconstitutional. Despite this, the detection and deportation of foreign nationals remained elusive.

The Election Commission is not empowered to detect or determine foreign nationals, as this is the prerogative of agencies like the Ministry of Home Affairs or the Foreigners Tribunals

In response, a massive exercise was launched — the updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam. After years of work and monitoring by the Gauhati High Court, the final NRC was published in 2019, which excluded around 19 lakh individuals. Ironically, a large number of those excluded were Hindus — contradicting the BJP’s political narrative that illegal immigrants were primarily Muslim Bangladeshis.

Meanwhile, the government brought in the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), aimed at providing citizenship to persecuted Hindus and other minorities from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh. But this too sparked a nationwide controversy, as many saw it as a move to offer citizenship on religious grounds while marginalising Muslims selectively.

Despite decades of agitation, legal reforms, and costly bureaucratic exercises, the government has failed to identify or deport even a few hundred foreign nationals conclusively. This glaring inefficiency raises a fundamental question: Is the issue of illegal immigration a real security threat or merely a recurring political tool?

Unanswered Questions

The government’s current strategy — of deleting names from voter lists instead of legally identifying and deporting foreign nationals — is analogous to striking someone’s name off a guest list without actually showing them the door. If there truly are foreign nationals living illegally, why not initiate lawful identification and deportation processes, rather than relying on unverifiable assumptions and mass deletions from electoral rolls?

This move also raises serious constitutional and legal questions. The Election Commission has no power to decide who is a citizen or a foreign national. Its role is limited to maintaining accurate electoral rolls based on documents submitted by applicants. It is not empowered to detect or determine foreign nationals, as this is the prerogative of agencies like the Ministry of Home Affairs or the Foreigners Tribunals under due legal process. If the EC has no authority to determine citizenship, how can it delete names from voter lists merely on the assumption that certain individuals are foreigners?

Such actions not only violate due process but also risk disenfranchising genuine Indian citizens, particularly marginalised communities who often face documentation issues. The answer may lie in the politics of polarisation.

Just as the Assam Agitation served as a powerful emotional trigger in the late 20th century, the present nationwide campaign may be aimed at reigniting nationalist sentiments — this time on a broader, national stage. With general elections in a number of States approaching, the narrative of protecting Indian sovereignty from ‘foreign infiltrators’ can be a potent campaign tool.

At What Cost?

But this political theatre comes at a cost — social harmony, bureaucratic integrity, and the credibility of democratic processes. India needs a balanced approach rooted in law and justice, not political expediency. If the state has credible intelligence and evidence, it should proceed with legal deportation mechanisms, respecting due process. Otherwise, repeated claims of “lakhs of foreign nationals” only serve to sow distrust and division among communities.

In the end, the issue appears to be less about actual foreign nationals and more about the strategic positioning of parties in the political battleground. As the BJP seemingly replays the Assam agitation on a national scale, one is compelled to ask: Is this really about national security, or just another chapter in the politics of manufactured threats?

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

Related News

-

Odisha government reviews protection of Lord Jagannath temple lands

3 hours ago -

Iran holds military drills with Russia as US carrier moves closer

3 hours ago -

This is taxpayers’ money: Supreme Court raps freebies culture

4 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Residents oppose Gandhi Sarovar Project over ‘forcible’ land acquisition

4 hours ago -

Australia level series as Indian women slide to 19-run defeat in second T20I

4 hours ago -

Karnataka beat Uttarakhand in semis, to face Jammu and Kashmir in Ranji final

4 hours ago -

Five Osmania varsity players in South Zone squad for Vizzy Trophy

4 hours ago -

Disciplined West Indies bundle out Italy with ease, tops Group C in T20 WC

4 hours ago