Opinion: India promised to end child labour by 2025. Reality is stark

School closures, poverty, and domestic labour continue to rob children of education and opportunity, even as India nears its 2025 deadline to end child labour

By Dr Deepa Palathingal, Sritirupa Dey, Baishali Mishra

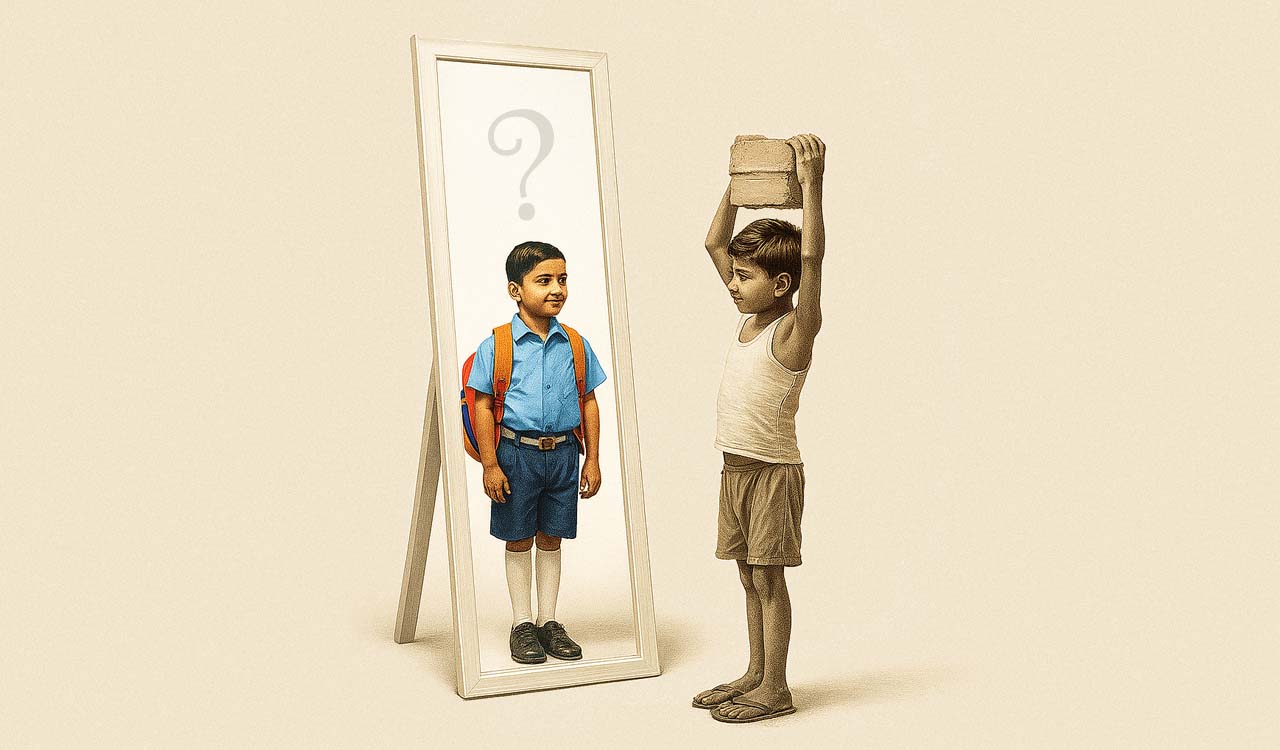

Five-year-old Janaki cooks every meal for her family. Not because she loves it, but because if she doesn’t, no one eats. She has never held a schoolbook, but she can tell you exactly how long dal takes to simmer and how to keep rotis from burning. This is not a story from a century ago — it’s India 2025, the year we were promised a child labour-free nation.

Also Read

In 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi set an ambitious goal: by 2025, no child in India would be forced into labour. Since then, the country has made notable progress — strengthening laws, expanding education programmes, and investing in digital learning platforms. Millions of children who once worked now attend school. These gains are worth celebrating. But as the deadline arrives, the reality is sobering. According to the government’s own Periodic Labour Force Survey, around 5 million Indian children aged 5-17 — about 2 per cent of all children — are still engaged in work.

This number excludes millions more who spend their days cooking, cleaning, or caring for siblings — work that never appears in official labour statistics. The 2019 Time Use Survey found that one in five children was engaged in unpaid domestic work on any given day, with girls (32.9 per cent) far more likely than boys (9.1 per cent) to shoulder these chores, especially in rural areas.

So, the question is no longer whether India has strong policies — it does. The real question is why they still fail to reach the children who need them most.

Progress and Gaps

Over the past two decades, India has built an impressive policy framework. The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, the Right to Education Act, and flagship programmes like DIKSHA (2017), NIPUN Bharat (2021) — which aims to ensure foundational literacy and numeracy by Grade 3 — and the PM SHRI scheme (2022), which is upgrading over 10,000 schools into model institutions with modern infrastructure and teaching practices, have created a strong base for reform. The National Child Labour Project has also been operational for years, targeting vulnerable districts with rehabilitation and education support.

Yet, in places like Marium Nagar in Ghaziabad district of Uttar Pradesh, children as young as four can be seen collecting scrap metal or hauling cattle feed instead of sitting in a classroom. This is not because parents don’t value education. In fact, in our every focus group discussion, parents express the same wish: “We don’t need free food. We just want free education and a proper system to ensure our children can go to school and return home safely. We can’t afford transport, and we can’t take time off work to escort them.”

Ending child labour is not just about fulfilling a moral obligation — it’s an economic imperative. Every child kept from school today is a loss to India’s future workforce and its aspirations for 2047

Another mother shared a stark reality: “Ever since their schooling stopped, we had no choice but to involve them in our daily struggles for survival. Children must learn something — if formal education is out of reach, then they are left to acquire the skills they would need in the future, even if it means working on construction sites, collecting scrap metal, or cooking meals for the entire family. At least this way, they gain some knowledge that might help them sustain themselves later in life.”

The Access Problem

Access remains a stubborn barrier. When the local free school in Marium Nagar closed two years ago, the nearest government school was suddenly five km away. This is not an isolated case — between 2017-18 and 2023-24, India saw a net decline of 76,800 government schools, a 7 per cent drop.

Many rural schools that remain open operate with just one teacher — more than 1.1 lakh schools fall into this category — and lack basic infrastructure like transport, computers, or internet. For children in remote villages, this means education is not just a right on paper but a daily logistical challenge.

The Invisible Workforce

India’s child labour debate often focuses on children in fields, factories, or street work. But for millions of girls, the workplace is their own home. Five-year-old Janaki spends her days cooking, sweeping, and caring for her younger siblings. These tasks keep her out of school just as effectively as a paid job would. Yet, official surveys like the PLFS rarely capture this invisible labour. This blind spot means policies designed to end child labour often fail to address one of its largest components: domestic responsibilities that rob girls of their childhood and education.

Why This Matters for Viksit Bharat 2047

Today’s 5- to 14-year-olds will be in their late 20s and early 30s when India hopes to achieve its vision of Viksit Bharat in 2047. Without decisive action, many will enter adulthood without the skills to thrive in a modern economy.

While national averages show low dropout rates — 1.9 per cent at the primary level, 5.2 per cent at upper primary, and 14.1 per cent at secondary in 2023-24 —these numbers hide deeper inequalities. Dropouts are significantly higher among rural children, girls, and those from marginalised communities. In some districts, household poverty and lack of transport still dictate whether a child studies or works.

Six actions that could change the future

Based on both field experience and international lessons, here’s what could make the difference:

- Reopen and build schools where they’re needed most: Reverse school closures in underserved areas. Provide safe, reliable buses for young children. In Brazil, tackling transport barriers increased enrolment by 30 per cent (Fiszbein, A, & Schady, NR (2009).

- Tie funding to measurable results: Link budgets to re-enrolment and sustained attendance. Reward districts that achieve targets, while providing targeted support to those that struggle.

- Create flexible, community-based education models: Bridge schools and adjusted schedules can help children who have dropped out re-enter formal education, as Ethiopia’s Alternative Basic Education programme has shown (Save the Children. (2022).

- Integrate family livelihood support with education goals: Welfare schemes like MGNREGA should be linked to households, withdrawing children from work. But caution is needed — research shows that in some areas, MGNREGA inadvertently increased child labour when adult work reduced supervision. Conditional cash transfers tied to schooling could avoid this (Ministry of Education. (2023).

- Acknowledge and address domestic labour: Recognise household work —especially by girls — as child labour in policy frameworks. Provide affordable childcare so older siblings can attend school.

- Make progress visible and public: Launch a Child Labour Dashboard tracking attendance, funding use, and intervention outcomes. Transparency creates both pressure and accountability.

From Promise to Proof

Ending child labour is not just about fulfilling a moral obligation — it’s an economic imperative. Every child kept from school today is a loss to India’s future workforce and its aspirations for 2047.

In 2017, India promised to end child labour by 2025. That promise has not yet been fully realised — but the progress so far proves change is possible. If we focus now on access, safety, and accountability, and treat every child’s education as an urgent national priority, we can close the remaining gap. Because if we don’t, the children collecting scraps in Marium Nagar today will still be struggling for survival in 2047— while the India we dreamed of remains just that: a dream.

(Dr Deepa Palathingal is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, CHRIST University, Delhi NCR Campus. Sritirupa Dey and Baishali Mishra are graduate students, School of Science, at the University)

Related News

-

Odisha government reviews protection of Lord Jagannath temple lands

2 hours ago -

Iran holds military drills with Russia as US carrier moves closer

3 hours ago -

This is taxpayers’ money: Supreme Court raps freebies culture

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Residents oppose Gandhi Sarovar Project over ‘forcible’ land acquisition

3 hours ago -

Australia level series as Indian women slide to 19-run defeat in second T20I

4 hours ago -

Karnataka beat Uttarakhand in semis, to face Jammu and Kashmir in Ranji final

4 hours ago -

Five Osmania varsity players in South Zone squad for Vizzy Trophy

4 hours ago -

Disciplined West Indies bundle out Italy with ease, tops Group C in T20 WC

4 hours ago