Opinion: India’s constitutional tug-of-war: Balancing Legislature and Executive

Executive delays undermine democratic processes, a concern at the heart of India’s ongoing constitutional debate

By Geetartha Pathak

On July 22, 2025, the Supreme Court of India issued notices to the Centre and all State governments in response to a Presidential Reference filed by President Droupadi Murmu. This reference seeks clarity on the constitutional powers of Governors and the President under Articles 200 and 201 of the Constitution, specifically regarding their roles in granting, withholding, or reserving assent to Bills passed by State Legislatures.

Also Read

The reference stems from a landmark SC judgment on April 8 in the case of State of Tamil Nadu vs Governor of Tamil Nadu, which addressed the actions of Tamil Nadu Governor RN Ravi in withholding assent to 10 State Bills. The Presidential Reference originates from a prolonged dispute between the Tamil Nadu government, led by the DMK, and Governor Ravi. Between January 2020 and April 2023, the TN Legislative Assembly passed 12 Bills, 10 of which were either withheld by the Governor or reserved for the President’s consideration without timely action.

The State government challenged this inaction, arguing that the Governor’s delays constituted an unconstitutional “pocket veto,” paralysing governance and undermining the will of the elected legislature. The court ruled that the Governor’s prolonged inaction and reservation of re-passed Bills for the President’s consideration were “illegal” and “erroneous.” It set specific timelines for action. Governors must decide on Bills within one month (or three months if acting without the Council of Ministers’ advice), and the President must act within three months of receiving a reserved Bill.

The court also expanded the scope of judicial review, allowing States to seek a writ of mandamus if these timelines are breached, and clarified that neither Governors nor the President can exercise an “absolute” or “pocket veto” under Articles 200 and 201. The reference raises some questions, which are concerned with:

• Judicial imposition of timelines

• Justifiability of actions

• Scope of Article 142

• Governor’s discretion and Council of Ministers

• Federal jurisdiction

• Presidential Reference under Article 143

• Validity of State laws

• Federalism and Centre-State relations

• Judicial role in Legislative processes

• Impact on other States

• Clarity on constitutional discretion

• Constitutional bench requirement

The reference seeks to resolve whether Governors and the President have unfettered discretion or are bound by constitutional norms, such as the advice of the Council of Ministers or judicially enforceable timelines. This could lead to the codification of conventions, reducing ambiguity in the Bill assent process. The SC noted that the reference affects “the entire country,” as similar disputes have arisen in Kerala, Punjab, and Telangana.

Comparative insights from Australia, Nigeria and Canada offer alternative models to balance Legislative authority and Executive discretion

This raises universal questions about the balance of power between Legislative and Executive authorities in federal or quasi-federal systems. Similar tensions exist in other countries with constitutional frameworks that assign the Bill assent powers to a head of state or governor-like figure.

Drawing Parallels

Parallels can be drawn with constitutional provisions and disputes in three countries — Australia, Canada, and Nigeria — each with federal or quasi-federal structures and comparable mechanisms for executive assent to legislation.

• Australia

In Australia, a federal parliamentary democracy, Section 58 of the Commonwealth Constitution outlines the powers of the Governor-General (the monarch’s representative) regarding Bills passed by the Australian Parliament. Like India’s Articles 200 and 201, Section 58 does not prescribe timelines for the Governor-General’s action, creating ambiguity similar to the Tamil Nadu case.

Australia has avoided judicially imposed timelines, relying instead on constitutional conventions that expect prompt action. State governors have similar powers under state constitutions (eg, Section 9 of the New South Wales Constitution Act 1902), but disputes are less frequent due to stronger conventions binding governors to act on ministerial advice. India’s reference, questioning the binding nature of the Council of Ministers’ advice, parallels debates in Australia about the extent to which governors can act independently.

• Canada

In Canada, another federal parliamentary democracy, Section 55 of the Constitution Act, 1867, governs the Governor General’s powers over Bills passed by Parliament of Canada. The Governor General can: Assent to a Bill, making it law, withhold assent, effectively vetoing the Bill (a power rarely used), reserve for the monarch’s assent, which transfers the decision to the UK government (now obsolete). At the provincial level, Lieutenant Governors perform similar roles under Section 90, which applies Section 55 mutatis mutandis (with appropriate modifications) to provincial legislatures.

A historical parallel to the Tamil Nadu case is the 1926 King-Byng Affair, where Governor General Lord Byng refused Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s request to dissolve Parliament, leading to a constitutional crisis. While this dispute centred on dissolution rather than the Bill assent, it raised similar questions about the Governor General’s discretionary powers and their potential to disrupt the legislative process.

More relevant to Bill assent is the rare use of reservation by Lieutenant Governors. For example, in 1937, Saskatchewan’s Lieutenant Governor reserved a Bill for the Governor General’s consideration, citing concerns over its constitutionality, prompting a debate over provincial autonomy versus federal oversight — akin to Tamil Nadu’s case.

Like India, Canada’s Constitution Act does not specify timelines for assent, but delays are rare due to established conventions. Canada’s reliance on conventions and political accountability minimises judicial involvement in Executive-Legislative disputes. The Tamil Nadu case’s judicial intervention, including the use of Article 142 to deem bills assented, contrasts with Canada’s preference for non-judicial resolutions, highlighting India’s more litigious approach to federal disputes.

• Nigeria

Nigeria, a federal presidential democracy, assigns the President powers over Bills under Section 58 of the 1999 Constitution, analogous to India’s Article 201. A notable parallel to the Tamil Nadu case occurred in 2018, when President Muhammadu Buhari repeatedly withheld assent to the Electoral Act Amendment Bill, citing procedural and constitutional concerns.

The National Assembly’s inability to muster a two-thirds majority to override the veto led to a legislative stalemate, reminiscent of Tamil Nadu’s challenge to Ravi’s delays and reservations. At the State level, similar disputes have arisen, such as in 2021 when the Benue State House of Assembly accused Governor Samuel Ortom of delaying assent to Bills, raising questions about Executive overreach in Nigeria’s federal system.

Unlike India’s Articles 200 and 201, Nigeria’s Section 58 explicitly mandates a 30-day period for Presidential action. The Tamil Nadu verdict’s judicial imposition of a one-month timeline for Governors aligns with Nigeria’s constitutional approach but lacks explicit constitutional backing in India. The Tamil Nadu verdict similarly expanded judicial review, allowing courts to intervene in cases of gubernatorial inaction, but Nigeria’s clearer constitutional provisions reduce ambiguity compared to India’s reliance on judicial interpretation.

The Presidential Reference in the Tamil Nadu Governor case underscores a universal challenge in federal systems in balancing Executive discretion with Legislative supremacy. Australia’s reliance on conventions, Canada’s convention-driven restraint, and Nigeria’s explicit timelines and override mechanisms offer contrasting approaches to India’s judicially enforced timelines and deemed assent.

The Supreme Court’s advisory opinion, expected in this month, could draw inspiration from these systems, potentially codifying conventions or affirming judicial oversight to ensure legislative efficiency while respecting constitutional roles. These international parallels highlight the need for clear, balanced mechanisms to prevent Executive delays from undermining democratic processes, a concern at the heart of India’s ongoing constitutional debate.

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

Related News

-

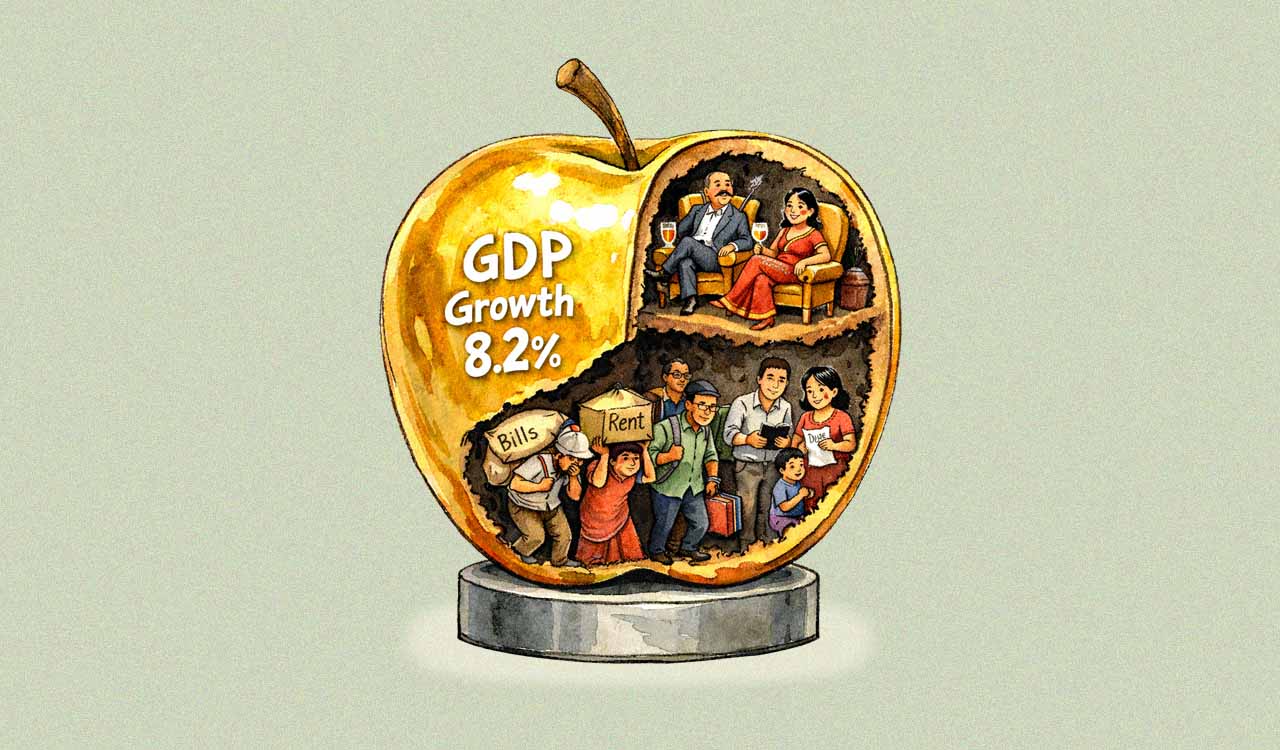

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

5 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

5 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

5 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

6 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

6 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

6 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

6 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

6 hours ago