Opinion: Kaleshwaram must be seen as a social welfare and development project

The malicious political narrative must move beyond narrow cost-benefit metrics to recognise KLIP’s role in correcting historical injustices, empowering the marginalised, and breaking cycles of poverty

By Chandri Raghava Reddy

The Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project (KLIP), since its conception and launch, has been subjected to blatant criticism by political opponents of the BRS and personal opponents of K Chandrashekhar Rao. What is interesting to note is that all the arguments levelled against the project remained largely uniform across political rivals and turncoats, suggesting a coordinated effort to discredit the project and thus belittle the efforts of the previous government.

Also Read

No other State or irrigation project in India has been as extensively used for political propaganda as Kaleshwaram, despite clear evidence of mishaps in the ongoing irrigation projects in other States. Unfortunately, the primary casualties of this malicious political campaign are the farmers of Telangana, who have been dreaming of reliable irrigation for their livelihoods, and the people in general for drinking water.

In today’s era of social media, misinformation spreads faster than truth, shaping narratives in ways that serve vested interests. It is striking that the malicious narrative surrounding KLIP lacks historical depth and fails to account for the broader social context through which the project’s merits should be evaluated. Against this backdrop, an attempt has been made to present a fact-based assessment, including a critical examination of contestations that extensively cite reports from Government of India agencies.

Plain Facts

The KLIP, inaugurated in June 2019, is recognised as the world’s largest multi-stage lift irrigation project, designed to reverse the flow of the Godavari River to irrigate Telangana’s historically parched farmlands. It spans 1,832 km, incorporating 203 km of tunnels and an extensive network of reservoirs, canals, and pump houses. The project lifts water from 100 metres at Medigadda to a height of 618 metres at Kondapochamma Sagar, filling reservoirs such as Mid Maner (25 TMC), Annapurna (3.5 TMC), Ranganayaka Sagar (3 TMC), Mallanna Sagar (50 TMC) Kondapochamma Sagar (15 TMC).

It is designed to irrigate approximately 45 lakh acres across 20 of Telangana’s 31 districts, providing irrigation water to 18 lakh acres of new ayacut while stabilising an additional 27 lakh acres of existing ayacut. Indirectly, till 2023, KLIP provided irrigation to about 20 lakh acres, particularly under the Sriram Sagar project, Nizam Sagar project and thousands of tanks and check dams.

What is noteworthy here is that it is not an ordinary or usual model of an irrigation dam or a barrage. In fact, the KLIP model stands out as a unique engineering model with no comparable project in India. Its design embodies the aspirations of the people, addresses longstanding grievances, and reflects a determined spirit against discrimination and neglect. Scholars quote ‘design of use is design for use,’ to emphasise the point that linear solutions cannot effectively resolve unique problems, an idea perfectly exemplified by KLIP.

Unlike conventional approaches that would have suggested constructing a massive dam across the Godavari-Pranahita confluence, raising environmental concerns, interstate water disputes and humanitarian issues, the KLIP offers an innovative solution through a non-linear approach. KLIP is an engineering marvel for its ingenious design, utilising the river itself as a reservoir throughout its course by lifting water upstream. About 38 TMC of water is stored in the Godavari River bed behind the gates of three Barrages, viz. Medigadda, Annaram and Sundilla without displacement of people, zero R&R, and in fact rejuvenated Godavari. This out-of-the-box thinking has circumvented major challenges while ensuring sustainable water management.

• Foodgrain Production

The project has driven a remarkable surge in agricultural output, particularly in foodgrain production. Telangana achieved the highest annual growth rate in foodgrain production among India’s top 10 States. However, critics, referring to the CAG report, which states that only 40,888 acres were irrigated by March 2022, a fraction of the targeted 18.25 lakh acres, argue that KLIP’s impact was limited.

However, upon cross-checking this claim with factual data on paddy cultivation in March 2022, published on January 15, 2023, in an English newspaper (which spearheaded a malicious campaign against the BRS during the Assembly elections and continues to do so), the figures tell a different story.

Data shows that, as of January 11, 2023, paddy was sown across 17,98,466 acres during the 2022-23 Rabi season. This was more than double the estimated sowing for that period (8,29,279 acres) and a four-fold increase compared to the 3,85,106 acres sown during the corresponding period in the previous year (2021-22). Therefore, the critics’ allegations were either based on misleading interpretations or reflected willful ignorance of the data. It may also be noted that paddy procurement rose by approximately 55% from 2018-19 to 2023-24, suggesting that the increased availability of paddy was a direct result of extended irrigation under the Kaleshwaram project.

• Groundwater levels

Beyond crop yields, the project has improved groundwater levels and reduced environmental stress. By filling water bodies and reservoirs, it has raised the groundwater table by an average of over 4 metres, which facilitated a tremendous increase in cultivation under borewells. The availability of reliable irrigation has contributed to a reduction in farmer suicides, with Telangana recording one of the highest declines in farmer suicides in India, earning it recognition as a model for agricultural resilience. The Kaleshwaram Project has thus presented a new Telangana to India and to the world with its acclaimed tag as the ‘Rice Bowl of India’ and a beacon of sustainable development.

This discussion has to be seen in a historical context to understand the nuances of the benefits of KLIP. The historical context was the persistent neglect of Telangana by the successive governments of Andhra Pradesh between 1956 and 2014, which did not use the Godavari water for Telangana. The Godavari basin has an estimated annual yield of 4,158 TMC at 75% dependability. This water was allowed to flow unused into the Bay of Bengal, with 500 TMC wasted in 2015 alone, instead of being diverted for Telangana’s drought-prone districts in northern Telangana.

Projects like the Sriram Sagar Project, initiated in 1963 on the Godavari in Nizamabad, were meant to irrigate Telangana but faced delays and underfunding. Its ayacut was jeopardised by upstream projects in Karnataka and Maharashtra and incomplete canal networks. Successive Andhra Pradesh governments did prioritise coastal Andhra’s irrigation while Godavari water use for Telangana lagged, allowing hundreds of TMC of Godavari water to flow unused to the sea, citing constraints like inter-State agreements, costs, and terrain complicated Godavari utilisation.

• Cost-Benefit Analysis

On the question of the cost-benefit analysis, here an attempt is made to compare Nagarjunasagar dam (only one dam is taken for easier understanding) with KLIP. Nagarjunasagar dam was built across the Krishna River between 1955 and 1967 with a cost of around Rs 130 crore at the time of construction. After adjusting for inflation, when we convert Rs 130 crore to 2025 terms, at a 7% average inflation rate, the cost in 2025 terms is approximately Rs 9,630 crore. Apart from power generation, it provided irrigation to 21.94 lakh acres through left and right canals. Notably, there were fewer environmental and politico-legal hassles. It took nearly 10 years to complete.

Data shows that, as of January 11, 2023, paddy was sown across 17,98,466 acres during the 2022-23 Rabi season. This was more than double the estimated sowing for that period (8,29,279 acres) and a four-fold increase compared to the 3,85,106 acres sown during the corresponding period in the previous year (2021-22)

Whereas KLIP, as of 2022-23, provided irrigation to about 20 lakh acres (new and stabilised ayacut). The construction involved 22 pump stations, about 1,800 km of canals, tunnels, and reservoirs, which were made operational by 2023. It used advanced lift irrigation, tunnels and large-scale mechanisation and weathered strict environmental and politico-legal clearances.

Kaleshwaram water reached the highest point in Telangana and, by gravity, flowed to the uppermost parts of the State. Rivulets like Haldivagu, Kudellivagu, revived, water in old open wells resurfaced and abandoned borewells became functional once again. After its commissioning, borewell rigs stopped entering many Telangana villages, a practice that had otherwise been a ritual every rabi season. Thus, on average, a typical Telangana village has been saving about Rs 50 lakh to Rs 1 crore per year.

Having access to irrigation water lifted the spirits of Telangana farmers. Many who had become daily wage earners, not only in Hyderabad and other towns across Telangana but as far away as Mumbai and Dubai, returned to their villages to till land once again. The transformation from despair to hope was striking, as farmers began to see a brighter future. With free electricity for agriculture, an abundant supply of quality seeds, fertilisers and pesticides, along with a robust procurement system for paddy through state-run centres, Telangana witnessed a golden era in agriculture, truly marking the realisation of ‘Bangaru (golden) Telangana’.

Beyond irrigation, KLIP delivers drinking water to villages, cuts labour for women and boosts incomes for small farmers. Mission Bhagiratha, an integral part of KLIP, reached 10 million people, tackling health and equity, which is core to welfare. It not only provided irrigation and groundwater recharge but also increased fish production by 70 per cent from 2014-15 to 2023-24 with a staggering annual production value of Rs 7,000 crore in 2024, thus providing direct and indirect employment, spurring rural growth, lifting marginalised communities from poverty and migration.

Battleground for Personal Vendettas

What is more shocking is that several political leaders, having witnessed the benefits of the project first-hand, actively participated in its vilification, ultimately harming the farmers they claimed to represent. Development should always take precedence over political ambitions, yet Kaleshwaram became a battleground for personal vendettas and short-sighted political expediency. What started as an attempt to settle personal scores by certain unscrupulous political figures escalated into a major political upheaval, culminating in significant consequences during the last Assembly elections.

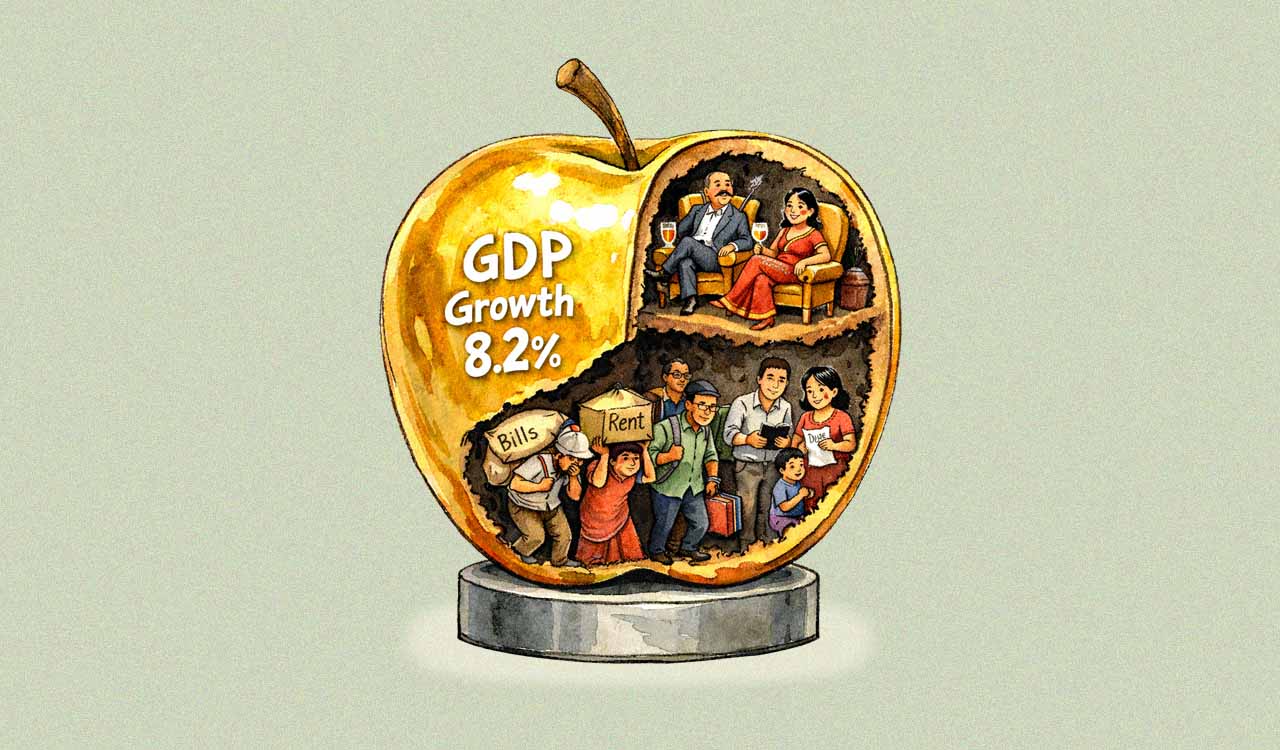

The cost of neglect by united Andhra Pradesh governments left generations underdeveloped, with economic, social and human losses of deprivation. It is to be reiterated in unequivocal terms that the state has the constitutional responsibility to uplift marginalised communities. Therefore, KLIP must be seen as a social welfare and development project, not just an irrigation project, shifting from a narrow lens of cost-benefit ratio to its role in righting historical wrongs, empowering the marginalised, and breaking cycles of poverty, a perspective that traditional economics often overlooks. KLIP’s cost is high, but so is the price of decades of neglect.

(The author is Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad)

Related News

-

HCA: Visaka Group will spend entire amount of Rs 64 crore on infrastructure in districts, says Vivek

3 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Indian boxers shine on day four at World Boxing Futures Cup

7 hours ago -

Nikki Pradhan achieves another milestone, completes 200 international caps

8 hours ago -

Telangana sets up Rythu Discom, liabilities of Rs 71,964 crore shifted

8 hours ago -

Iran targets ships, Dubai airport in Gulf escalation

8 hours ago -

FIH Qualifiers: India scores big win against Wales, storm into semifinal

8 hours ago -

India allows FDI under automatic route for firms with less than 10 per cent Chinese stake

8 hours ago -

IEA agrees to record emergency oil release to calm global prices

8 hours ago