Opinion: Monroe Doctrine reloaded—Venezuela, power politics, and return of the jungle order

US action reflects a revived Monroe Doctrine, driven by geopolitics, energy security, and regional power competition — not oil alone, but oil first among equals

By Brig Advitya Madan (retd)

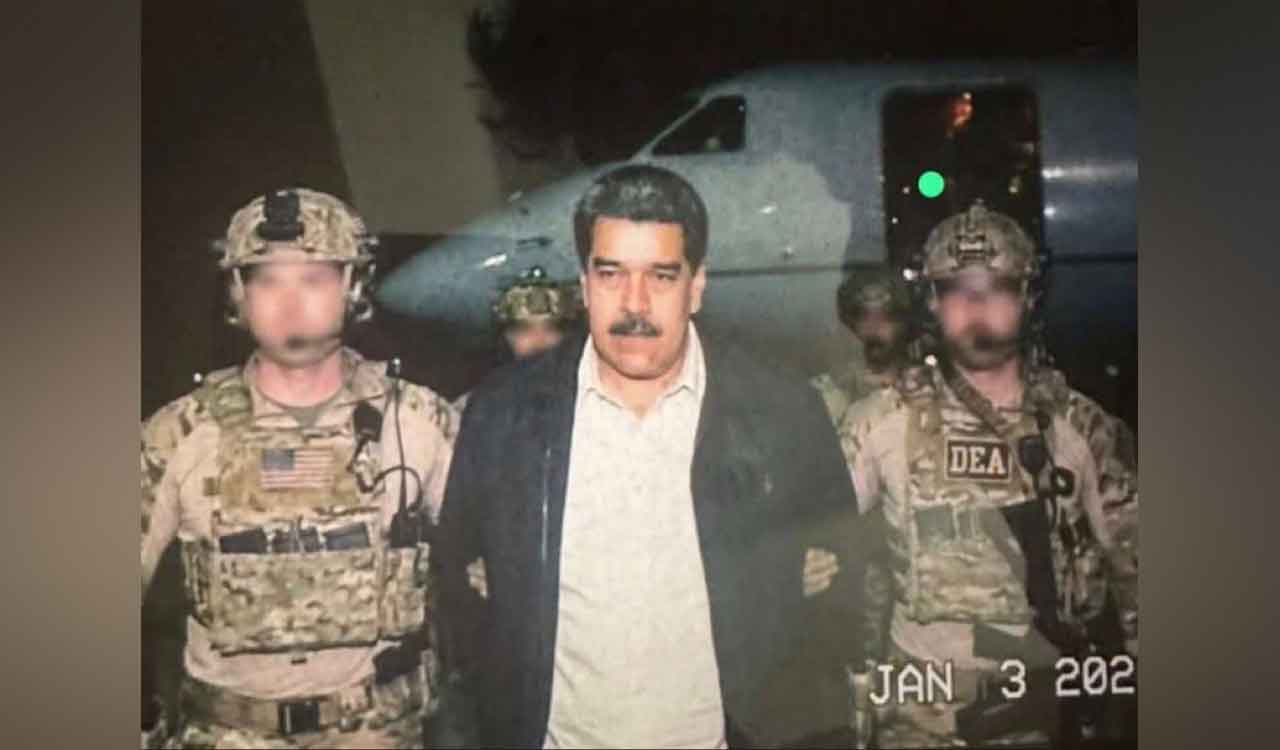

What unfolded in Venezuela on 3 January 2025 — if early reports are even partially accurate — marks a moment of profound geopolitical consequence. According to widely circulating accounts, a covert, CIA-led operation, reportedly backed by elite US forces, struck two major Venezuelan military installations — Fuerte Tiuna and La Carlota — and resulted in the custody of a sitting Venezuelan President.

The striking aspect of the episode is not merely its audacity, but the apparent absence of resistance. Either Venezuela’s air defences were neutralised through a meticulously planned cyber and electronic operation, or the episode involved deep internal complicity. In either case, the message is unmistakable: when a great power decides to act decisively in its perceived sphere of influence, norms and niceties take a back seat.

Monroe Doctrine

The more important question, however, is not how the operation was conducted, but why the United States chose to execute such a bold move. To understand that, one must step back and examine the broader contours of US strategic thinking — and its historical roots.

A few days ago, I wrote about the evolving US National Security Strategy. One paragraph in particular merits renewed attention today: the explicit reference to the Monroe Doctrine. First articulated in 1823 by President James Monroe, the doctrine declared that the Western Hemisphere was closed to further European colonisation, while the United States, in turn, would refrain from interference in European affairs. At the time, the US was neither the economic nor military colossus it is today, and much of Latin America had just emerged from colonial rule. The doctrine was aspirational then. Two centuries later, it is actionable.

What we are witnessing now is the Monroe Doctrine in its modern, muscular incarnation. The most pronounced focus of America’s contemporary strategic posture is the Western Hemisphere, particularly Latin America. In official documents, the US identifies three primary threats emanating from the region: illegal migration, drug trafficking, and transnational organised crime. This framing dovetails neatly with President Donald Trump’s domestic political narrative and helps explain his statement on 19 December 2025, when he openly said he did not rule out the possibility of war with Venezuela.

Behind US Actions

From this vantage point, the rationale behind Washington’s actions becomes clearer. US interest in Venezuela is driven by a complex mix of geopolitics, energy security, and regional power competition — not oil alone, but oil first among equals. Venezuela possesses the largest proven oil reserves in the world, conferring enormous long-term strategic value. Crucially, it sits squarely in America’s geopolitical backyard, at a time when both China and Russia have been expanding their footprint in Latin America. Russia’s sale of advanced air defence systems to Caracas is a case in point.

Energy considerations loom equally large. Control — or at least decisive influence — over Venezuelan oil would allow the United States to stabilise supply and prices across the Western Hemisphere. This matters not just for markets but for domestic politics. US Gulf Coast refineries are structurally designed to process heavy crude, precisely the kind Venezuela produces, rather than the light shale oil of which the US already has an abundance. From a purely industrial standpoint, Venezuelan oil fits a critical gap in the American energy ecosystem.

What is playing out before our eyes is not the much-vaunted ‘rules-based international order,’ but something far older and cruder: Might determines outcomes

Then there is the great-power rivalry dimension. Washington is keen to prevent China, Russia, and Iran from entrenching themselves in Venezuela and gaining privileged access to its resources. In this sense, US behaviour mirrors what China is doing in its own neighbourhood — whether in the South China Sea or around Taiwan. Spheres of influence may be unfashionable in diplomatic rhetoric, but they are alive and well in practice.

Mass migration from Venezuela over the past few years adds another layer of urgency. Millions fleeing economic collapse and political instability have strained neighbouring states and, indirectly, the US itself. For Washington, stabilising — or reshaping — Venezuela is, therefore, seen as both a security imperative and a domestic political necessity.

Recent statements by senior US leaders reinforce this interpretation. Vice President JD Vance’s remark that Venezuela must return its “stolen oil,” coupled with allegations of drug trafficking against its leadership, frames the issue as one of justice and restitution. Trump’s more blunt assertion — made shortly after the operation — that the US would “control Venezuela and its oil resources” strips away any remaining ambiguity. This is power politics, plainly stated.

One must also factor in America’s own economic stresses. With mounting debt, persistent inflationary pressures, and strategic competition on multiple fronts, the US has strong incentives to secure tangible economic assets. Venezuelan oil, in this context, is not just a geopolitical prize but an economic lever.

Lessons for India

For India, the lessons are stark and uncomfortable. When the chips are down, no country — and certainly no multilateral institution — will ride to your rescue. Neither the UN Security Council nor the UN General Assembly has the will or capacity to restrain a determined great power acting in its perceived national interest. The only credible insurance policy is self-strengthening.

India must, therefore, invest far more seriously in its own security and economic resilience. Defence spending of 4-5% of the GDP should not be seen as extravagant, but as prudent insurance in an increasingly anarchic world. Military capability must be matched by economic strength, technological self-reliance, and political unity on matters of national security.

In truth, Venezuela should have seen this coming. In September 2025, the US launched Operation Southern Spear, targeting drug boats allegedly linked to Venezuela. Eleven people were killed in the initial strike, followed by a series of maritime attacks between September and December that reportedly resulted in over a hundred deaths. These were not isolated incidents, but signals that escalation was underway. Today, it is Venezuela. Tomorrow, it could be Iran or Cuba. China has already made clear that it considers its moves on Taiwan inevitable. Russia showed the world its hand in Crimea in 2014 and again in Ukraine.

To summarise, what is playing out before our eyes is not the much-vaunted “rules-based international order,” but something far older and cruder: the rule of the jungle. Might, not moralising, determines outcomes.

For India, the imperative is clear. We must remain politically united on national security, focus relentlessly on strengthening our armed forces and economy, and abandon any comforting illusions about how the world works. In the emerging global order, survival — and influence — will belong to those who are prepared.

(The author is a retired Army officer)

Related News

-

Investigation suggests US Tomahawk cruise missile hit girl’s school in Iran

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Pakistani national convicted in US for Iran-linked plot to assassinate Donald Trump

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Major pipeline leak disrupts water supply in Hyderabad suburbs

7 mins ago -

Telangana Women Moto Bikers celebrate Women’s Day with vibrant gathering in Financial District

15 mins ago -

IIMC Khairatabad conducts Online Commerce Talent Test with global participation

16 mins ago -

From Lagacherla to Madhu Park Ridge, land acquisition disputes haunt Congress government

21 mins ago -

Smoke emanates from TGSRTC bus in Karimnagar district; passengers shifted safely

32 mins ago -

Government teacher found hanging in Kothagudem; family alleges foul play

36 mins ago -

IHM Hyderabad opens admissions for B.Sc. Hospitality course for 2026–27

1 hour ago -

Sharjeel Imam gets 10-day interim bail in 2020 Delhi riots case

1 hour ago