Opinion: The return of imperial bullying in a multipolar world

US intervention in Venezuela highlights a global resurgence of great-power coercion, where international law is increasingly sidelined

By Geetartha Pathak

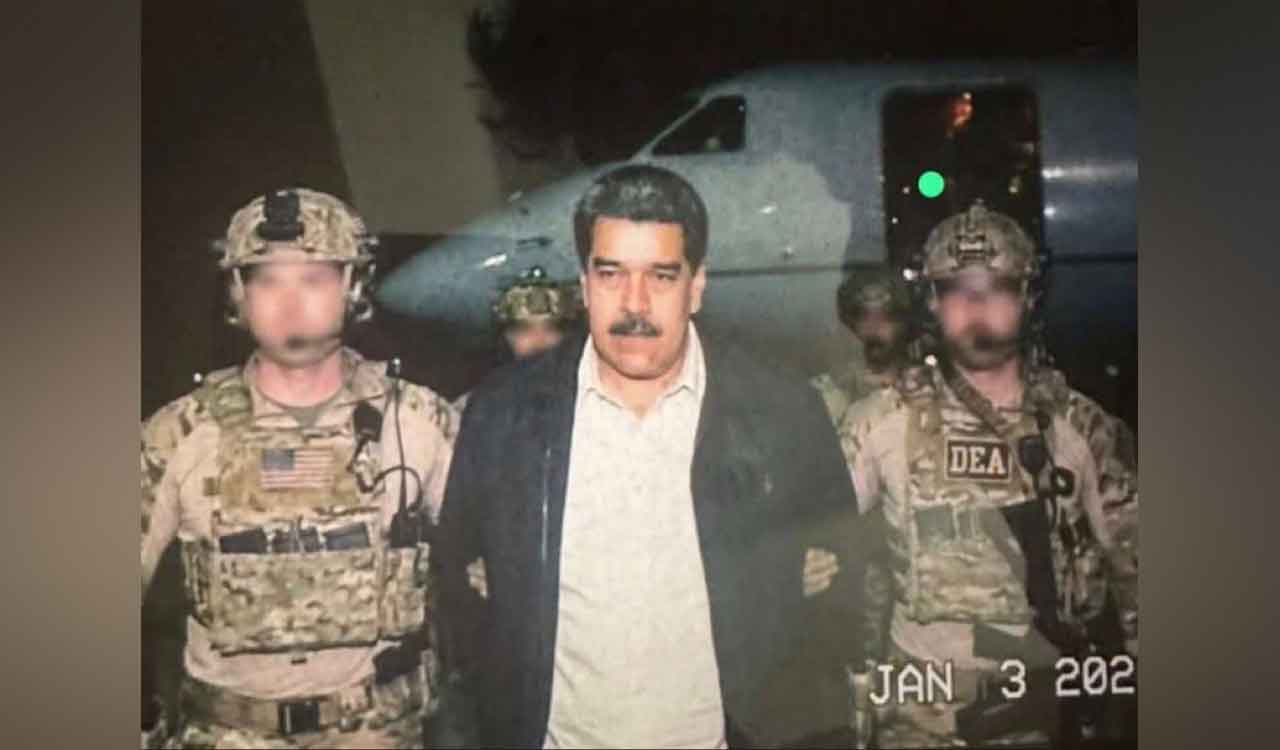

The United States’ military operation in Venezuela on January 3, 2026, marks a brazen violation of international law and serves as a stark reminder of unchecked power in global affairs. This audacious move, executed without United Nations sanction or consultation with regional allies, harks back to an era when great powers imposed their will on weaker nations with impunity.

Also Read

President Donald Trump’s declaration that the US would “run” Venezuela until a “safe, proper and judicious transition”, coupled with repeated references to the country’s vast oil reserves, underscores the economic motives behind the intervention. This is not mere regime change; it is a revival of 19th-century imperialism, repackaged in the contemporary language of counter-narcotics, hemispheric security, and democratic restoration. The pretext — allegations of Maduro heading a “narco-terrorist” cartel— lacks publicly substantiated evidence from independent sources.

By bypassing the United Nations Security Council and flouting Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, Washington has positioned itself as the self-appointed arbiter of global norms, eroding the post-World War II order designed to protect weaker states from great-power predation.

Power Hegemony

Yet, this is not an isolated American aberration in an otherwise rule-bound world. Great powers across the board have increasingly resorted to coercive tactics, exploiting asymmetries in military, economic, and technological strength to bend smaller nations to their will. Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, justified under the dubious guise of “denazification”, devastated a sovereign neighbour, while China’s assertive territorial claims in the South China Sea have openly defied the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in favour of the Philippines, underscoring Beijing’s disregard for international maritime law. Economic coercion — from China’s trade pressure on Lithuania and Australia to Russia’s energy cutoffs to Moldova — further illustrates how power asymmetries are weaponised.

In South Asia, border disputes and economic leverage have strained relations between rising powers and their neighbours. India’s 2020 border clashes with Nepal over territorial maps and its influence over Bhutan’s foreign policy amid the Doklam standoff with China illustrate how regional giants can pressure smaller states. Even in Africa, the landscape is marred by proxy influences: Russia’s Wagner Group (now rebranded as Africa Corps) has meddled in Mali, the Central African Republic, and Sudan through private military operations, providing security in exchange for resource concessions, while China’s Belt and Road Initiative has ensnared countries like Sri Lanka and Zambia in debt traps, leading to the handover of strategic assets such as ports and mines.

A ‘Three-bully World’

These parallels highlight a troubling convergence: a “three-bully world” dominated by the US, China, and Russia, where multilateral institutions like the UN are sidelined, and might dictate right over international law. For smaller and weaker nations — from Latin America to Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Global South — the threats are multifaceted and existential.

As the US, China, and Russia assert dominance, smaller nations face growing threats to sovereignty, stability, and economic independence

Military escalation lowers the thresholds for conflict, fostering a climate of paranoia where leaders of small nations divert scarce resources from education and healthcare to domestic militarisation. Russia’s energy cutoffs to Moldova in 2022-23, amid the Ukraine war, exemplify how hybrid warfare — combining economic coercion with disinformation — amplifies these vulnerabilities.

Sovereignty erodes insidiously as foreign aid, trade agreements, and investment packages are conditioned on political alignment, exacerbating internal divisions and paving the way for proxy wars. The spillover effects are profound: refugee flows destabilise entire regions, disrupted global supply chains inflate commodity prices, and chronic instability breeds terrorism, hitting import-dependent small economies hardest.

The US’ 2025 attempts to bully African nations like Kenya and Ghana into accepting mass deportees under threat of aid cuts further illustrate how even immigration policies become instruments of coercion. Powers that decry others’ aggression often mirror it in their own spheres: the US condemns Russian expansionism in Europe while asserting unchallenged hemispheric dominance in Latin America; China critiques Western interference in Asia amid its own assertive claims in the Taiwan Strait and beyond; Russia rails against NATO encirclement while encroaching on former Soviet states like Georgia and Kazakhstan.

As competition intensifies in a multipolar world, smaller nations risk becoming collateral damage in proxy battles over resources, influence, and ideology. For vulnerable states navigating this treacherous landscape, survival demands proactive and multifaceted safeguards.

Strengthening multilateral coalitions remains crucial — revitalising forums like the Non-Aligned Movement, which once united over 120 countries against Cold War blocs, or regional bodies such as ASEAN in Southeast Asia and CELAC in Latin America. These platforms can amplify collective voices against unilateralism, pushing for urgent UN reforms, including limits on veto powers in the Security Council to prevent interventions like Venezuela’s from becoming normalised.

Legal avenues offer tangible recourse: the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has proven effective in past cases, such as Nicaragua’s 1986 victory against US mining of its harbours or the Philippines’ 2016 arbitral win against China’s South China Sea claims, providing precedents for challenging coercive actions through jurisprudence. Economic diversification is equally imperative — reducing overreliance on single commodities through strategic investments in renewables, agriculture, digital technology, and human capital can blunt the impact of sanctions and market manipulations.

Expanded intra-regional trade pacts, such as an invigorated BRICS+ framework or the African Continental Free Trade Area, provide viable alternatives to great-power-dominated systems like the World Trade Organization, fostering self-reliance and mutual support among the Global South.

Myanmar’s post-2021 coup policies, despite challenges, underscore the importance of vigilant economic planning to avoid falling into neo-colonial debt traps. Global advocacy, amplified by resilient civil society organisations, independent media, and transparent investigative reporting, can expose the human and fiscal costs of interventions, building international pressure for restraint.

Digital campaigns and whistleblower networks have already swayed public opinion in cases like the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, highlighting moral hazards and long-term quagmires. Within aggressor nations themselves, domestic opposition — mobilised by advocacy groups highlighting the astronomical fiscal burdens (such as the billions spent on Venezuela operations) and ethical dilemmas — may temper imperialist impulses, drawing sobering lessons from historical failures like Vietnam, Iraq, or the Soviet-Afghan debacle.

Ultimately, the path ahead requires a resolute recommitment to principled multilateralism. Historical shifts, from the exploitative colonial norms of the 19th century to the post-war prohibitions on conquest enshrined in the UN Charter, prove that systemic change is possible when collective will prevails.

Venezuela’s crisis must not become a template for normalised bullying but a catalyst for global reform. In a world overshadowed by giants, small nations’ resilience lies in strategic unity, diplomatic agency, and innovative self.

As India, with its enduring tradition of non-alignment and advocacy for the Global South, navigates these turbulent waters, its emphasis on dialogue, peaceful coexistence, and unwavering respect for international law offers a compelling model for balancing power dynamics without succumbing to hegemonic pressures. The alternative — a descent into anarchic rivalry — serves no one’s long-term interests, least of all the bullies themselves.

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

Related News

-

Opinion: US intervention in Venezuela — Sovereignty under strain

-

Vance to meet Danish and Greenlandic officials in Washington as locals say Greenland is not for sale

-

Opinion: Monroe Doctrine reloaded—Venezuela, power politics, and return of the jungle order

-

Opinion: America turns inward—what Trump’s new National Security Strategy means for the world, and India

-

More Indian-flagged LPG tankers lined up to cross Strait of Hormuz

26 seconds ago -

A Policeman Who Led by Example: Remembering HJ Dora

3 mins ago -

Sonam Wangchuk released from Jodhpur jail after Centre revokes NSA detention

17 mins ago -

Case registered after class 1 student made to stand in sun for 2 hrs as punishment in Bengaluru

19 mins ago -

Election process for UN Secretary-General to start next month with five candidates so far

32 mins ago -

Clashes erupt between TMC, BJP workers in Kolkata ahead of PM’s rally; policeman, BJP leader injured

40 mins ago -

Surrendered Maoist leader Devuji seeks lifting ban on CPI (Maoist)

50 mins ago -

White House now begging world, including India, to buy Russian oil: Iran

55 mins ago