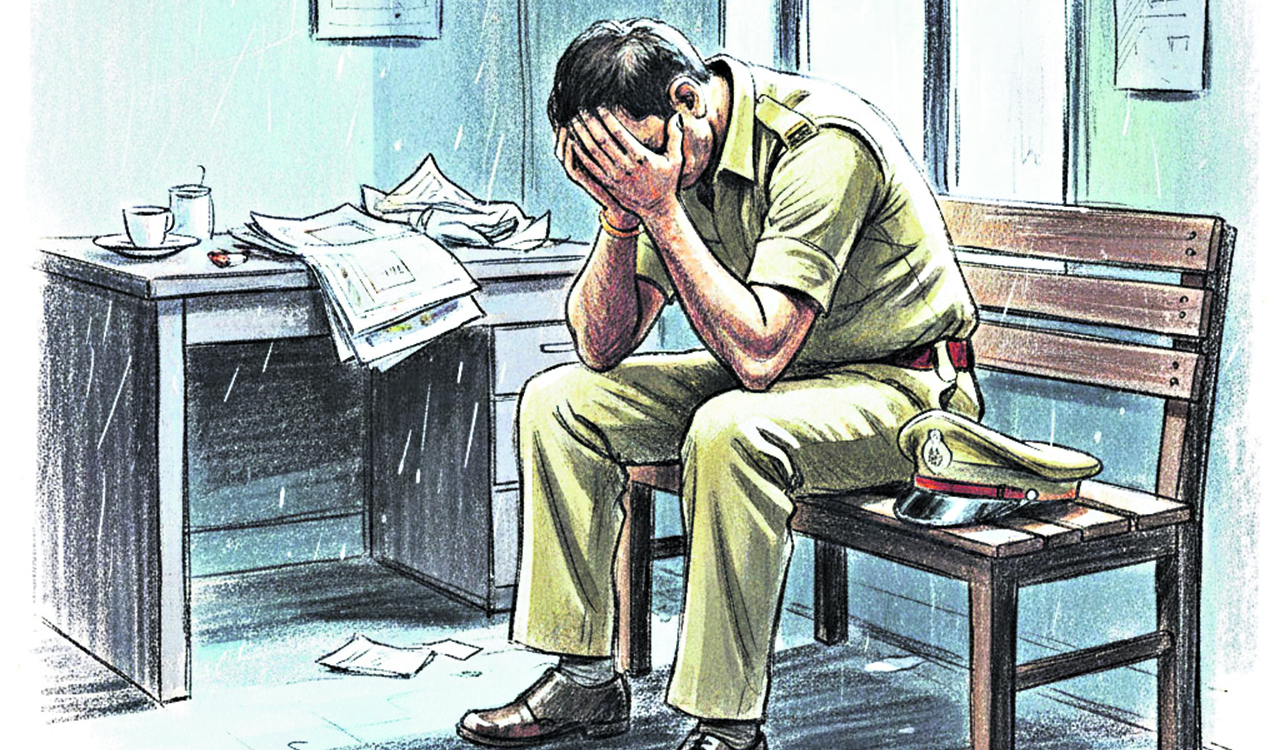

Opinion: Why do some policemen commit suicide?

Philosophical balance and inner calm, valuing life over status, power and money, can protect an officer’s life

By B Maria Kumar

Whenever I read about suicides, I am reminded of the intriguing words of my close friend and batchmate in the Indian Police Service, Ashok Dohare, who was also my cadre mate in Madhya Pradesh. He once remarked, half in jest and half in seriousness, that the purpose of human life is twofold — to procreate and to commit suicide.

When I recently heard of two shocking suicides in the Haryana Police Department, Dohare’s mysterious logic echoed again in my mind. Having been a policeman myself in the past, I felt not only a comrade’s sorrow but also deep concern about what might have befallen the two officers and our police organisation as a whole. The deaths of police colleagues leave a huge void in the department and in the lives of those who knew them, reminding us of John Donne’s timeless insight that no man is an island.

Puzzling Dilemma

The police service, perhaps more than most institutions, thrives on fraternity, discipline, morale, and teamwork that bind its members together. In that sense, the two officers’ ultimate acts become a turning point, shaking the very foundations of the uniformed force and its spirit of unity. Had Albert Camus, the Nobel Prize-winning philosopher of the absurd, been alive, he might have interpreted these tragedies in unthinkable yet metaphysical ways. Unlike Dohare, who spoke of suicide as the fate of all living beings collectively, Camus’ view, like that of sociologist Émile Durkheim, was limited to human beings.

Yet Camus differed from Durkheim in that the latter viewed suicide through a sociological lens, while Camus treated it as an existential problem — the mind’s rebellion against the absurd. Returning to the puzzling dilemma that never ceases to haunt, how does one take one’s own life?

We seldom discuss Arthur Koestler, a disillusioned communist and co-author of ‘The God That Failed’, who supported euthanasia and ended his life along with his wife. But unlike Koestler, the two police officers wanted to live, and yet they ended their lives. In truth, most victims of suicide love life but are defeated by something more overpowering than the instinct to live. If we think deeply, we may see even humanity at large moving slowly but surely towards self-destruction.

Let us set aside the threat of nuclear annihilation or Durkheim’s idea of altruistic self-sacrifice. Consider instead the quiet, everyday forms of self-harm, such as indulgence in harmful addictions, overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, persistent inhalation of toxic air, or the nurturing of unhealthy relationships.

In countless subtle ways, the so-called intelligent species, Homo sapiens, moves toward self-inflicted extinction step by step. The real difference between this and police suicides lies only in the pace of dying — some lives end quickly while others fade slowly. How far we can delay the approach of intentional death depends on the severity of our psychological stress.

Triggers of Self-killing

Paradoxically, many of these triggers of self-killing are within our control, yet we fail to address them. Ignorance, arrogance, and malevolence stand in the way of healing the suffering souls. Even when unseen, suicidal tendencies quietly make their way into every life, affirming Freud’s idea of the death instinct as a silent undercurrent of existence. Recent surveys reveal that growing cracks in interpersonal relationships are one of the major causes behind rising suicides. This finding highlights how malevolence, the dark counterpart of fraternity, deepens the misery of the already troubled and worried minds.

Reassessing camaraderie and introducing a living guide across ranks can fortify bonds of fraternity within the force

Numerous scientific studies indicate that corrosive interactions like blaming, scapegoating, shaming, and teasing, inflict serious and lasting damage on mental health. They ignite unpredictable impulses and often weaken the will to live. In such conditions, malevolent behaviours such as ill will, hatred, and prejudice — when directed at vulnerable individuals — can act as accelerators, pushing the persons much closer to the edge of voluntary death.

Camus views it as life-negation because, for the prospective victims, unbearable pain and suffering repeatedly obstruct the path towards meaning in life. When life appears meaningless, it hastens the journey towards the final breath, as they seek to escape from an indifferent and absurd world.

Embedding Philosophical Ethos

Though this view applies to humanity at large, it holds even greater relevance to police organisations. Just as drivers navigating erratic traffic are statistically among the most stress-prone individuals, police personnel also face exceptionally high levels of stress arising from health-threatening working conditions and complex professional burdens. Research shows that these strains, compounded by occupational pressures and societal neglect, can weigh heavily on the mental resilience of police personnel.

Given this reality, the police department must pay special attention to the philosophical dimension of policing, which concerns the deeper questions of life and congenial human coexistence. It unequivocally emphasises balance and inner calm in life, placing status, power, money, name, and fame in the realm of insignificance. This perspective is particularly pertinent to the way the police personnel interact with one another, as well as how they respond to public grievances related to crime, law, and order.

Therefore, embedding philosophical ethos in the practice of interpersonal relations is not a matter of choice but of genuine necessity. It nurtures sensitivity, understanding, and a collaborative culture among police professionals who stand shoulder to shoulder in the demanding field of public service. Any tense situation in the chain of command invariably arises from strained personal dynamics and can lead to unfortunate repercussions for fellow officers involved if not handled in time with mutual respect and empathy.

Hence, a philosophical outlook helps police personnel value their ties with colleagues and prioritise what truly matters in real life over what does not. It prompts them to display humane fairness and compassionate solidarity, which serve as effective decelerators against stressors.

Moreover, a philosophical attitude also enables them to find meaning in their profession and in life itself. Therefore, the police organisation can reassess the climate of camaraderie across all ranks and adopt a living guide to fortify bonds of fraternity. Such a measure can help dispel the despair that sometimes leads to suicide and further strengthen the sense of shared unity within the force.

(The author, a recipient of National Rajbhasha Gaurav and De Nobili awards, is a former DGP in Madhya Pradesh)

Related News

-

Modi, Macron vow deeper defence, trade partnership

5 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Dharani, Tapasya clinch honours

5 hours ago -

Man arrested for cultivating ganja plants in Telangana’s Adilabad

6 hours ago -

Second successive win for Titans in Samuel Vasanth Kumar basketball

6 hours ago -

Women councillors allege misconduct by Congress in Kyathanpalli

6 hours ago -

Gauhati Medical College doctor lodges FIR alleging harassment by principal

6 hours ago -

Two FIRs filed in Chikkamagaluru after week-long stone pelting on house

6 hours ago -

Viral video shows SUV hitting biker in Dwarka, teenage driver detained

6 hours ago