Rewind: Desert Dancer — Enduring grace of the Chinkara

In a world where wilderness is shrinking, India’s gazelle stands as a quiet symbol of resilience, and a reminder that even the deserts are full of life worth preserving

By N Shiva Kumar

Dainty, delicate, and adorable, the chinkara is one of the smallest antelopes in the world, yet it moves with astonishing grace and agility. Sighting one at close quarters is a rare privilege, as these shy and wary creatures keep a safe distance from humans. Once hunted by people and pursued by natural predators such as leopards, wolves, and jackals, the chinkara now faces a far more relentless enemy, the feral dogs. Unruly and uncouth in their hunting ways, the ferocious feral dogs pose a grave threat to free-ranging wildlife across India’s open landscapes.

Also Read

In the wavering shimmer of India’s desert heat, a delicate silhouette darts across the horizon, its slender legs in flight, curved horns slicing through the golden light. This is the chinkara (Gazella bennettii), or the Indian gazelle, one of the most graceful and enduring symbols of India’s arid wilderness. Sometimes called the Jabeer Gazelle in parts of Rajasthan and Gujarat, the chinkara stands as a quiet testament to the resilience of life in the harshest of landscapes. Having observed and photographed them in certain parts of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Gujarat, and Haryana during my birding jaunts in the wild, I found chinkaras to be extremely cautious.

Recently, I was fortunate to encounter the enduring chinkara in two of the seven sprawling rocky, scrubland, and grassland terrains of the Deccan Plateau surrounding Bhigwan in Maharashtra. On a swift impulse, I had decided to explore a few of these grasslands, embarking on a 460-kilometre road journey from Hyderabad with an avid birder. Bhigwan was our base camp, and we spent nearly seven hours daily traversing different grasslands within a 50-kilometre radius of this tiny yet vibrant town. We were guided by a knowledgeable naturalist-cum-driver who knew the lay of the land like the back of his hand.

There are about 91 species of antelopes in the world, of which India is home to six, the nilgai (blue bull), Tibetan antelope (chiru), Tibetan gazelle, blackbuck, chinkara, and chousingha. Among these, the nilgai is the largest, while the chousingha, the only four-horned antelope in the world, is the smallest. It is important to note that antelopes should not be confused with India’s 12 species of deer, which range from the tiny Indian mouse deer to the majestic sambar, the largest of them all.

Sculpted by the Desert

Found across the vanishing grasslands, rocky plateaus, and semi-deserts of western and central India, the chinkara is exquisitely adapted to heat and scarcity of minimal resources. Measuring just about 65 cm (nearly three feet) at the shoulder and weighing between 20 kg and 27 kg, this small antelope is built for survival. Its sand-coloured coat mirrors the desert earth and fading grasslands, offering near-perfect camouflage from predators like wolves and leopards.

Fleet-footed

- Slender, sandy-brown body with white underparts

- Dark facial stripes from eyes to muzzle

- Long, ringed, lyre-shaped horns (up to 30 cm) in males

- Can survive without direct water intake for weeks

- Is shy, solitary, and sometimes found in mini groups. A swift runner and known for its high leaps (stotting) when alarmed

- Revered by the Bishnoi community in Rajasthan and protected under India’s Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (Schedule I)

- Conservation Status: Least Concern (according to IUCN) but faces localised decline due to habitat loss, poaching, and fragmentation of grasslands

- The chinkara can run at speeds of up to 60 km/h, and in the blazing deserts of Rajasthan or the rocky plains of the Deccan Plateau. It often shares its home with the blackbuck and the elusive desert fox

What’s truly remarkable, however, is its ability to live without direct water for long periods. The chinkara extracts moisture from the morning dew on grasses and the sap of desert shrubs. Even the succulence of wild fruits and herbs provides enough moisture, a trait that allows it to thrive even in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan, where summer temperatures soar beyond 45 degrees C. I recall how, participating during a tiger census in Ranthambore National Park, a pair of chinkara would often check us out with curiosity as we sat on a treetop machan making a checklist of wildlife.

Grace in Motion

If there’s poetry in motion, the chinkara writes it with every leap. When alarmed, it performs a series of high, springing jumps known as stotting, both to signal alertness and to confuse predators. These swift and bounding movements are not just survival tactics but spectacles of sheer elegance, one of the reasons the animal has long been celebrated in Rajasthani folklore and miniature art.

A male chinkara is also a loner most of his life, except when mating and is much bolder than the female in its demeanour. Photo: N Shiva Kumar

Despite its delicate frame, the chinkara is far from fragile. Males are equipped with ringed, lyre-shaped horns that can reach up to 30 cm in length, used in ritualised duels during the breeding season. Unlike many herd-dwelling antelopes, chinkaras prefer to be solitary or found in small family groups, choosing to live quietly, away from human intruders.

Where the Grass Still Whispers

Once widespread across South Asia, from Pakistan and Iran to the dry Deccan Plateau, the chinkara’s prime strongholds today are the Rajasthan desert, Kutch in Gujarat, the plains of Madhya Pradesh, and parts of the Deccan Plateau and Gangetic grasslands.

In Rajasthan’s Desert National Park and Velavadar Blackbuck National Park in Gujarat, chinkaras roam freely alongside blackbucks and desert foxes, forming part of a delicate yet vibrant ecosystem. Their presence indicates healthy grasslands, which are often the most neglected of India’s ecosystems, habitually rejected as wastelands.

Sacred Bond

The chinkara’s fate in India is deeply intertwined with local culture and religion. The Bishnoi community of Rajasthan, known for their deep environmental ethics, considers the chinkara and blackbuck antelopes as sacred. They protect these animals with fierce devotion, a relationship that became legendary after the tragic case of actor Salman Khan’s 1998 blackbuck and chinkara hunting incidents, which brought national attention to wildlife conservation laws and the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972. Even today, most Indians assume a chinkara to be a deer, and many have not even seen one in the wild.

In the arid expanse of Deora village in Chitalwana, Jalore, a former CRPF personnel has quietly become a lifeline for Rajasthan’s dwindling wildlife. Peera Ram Dayal Bishnoi, at 58 years, runs a ten-acre rescue and rehabilitation centre for injured and abandoned wild birds and animals with his family members. A trained veterinary doctor, Bishnoi has rescued and treated more than 60 chinkaras over the years, particularly those victims of road accidents, poaching, or attacks by feral dogs. Once nursed back to health, every animal is released into the wild, a testament to his commitment to conservation beyond words. He is a recipient of a few national nature awards.

Peera Ram Dayal tends to an array of antelopes and deer in his ten-acre rescue and rehabilitation centre in rural Jodhpur. Photo: N Shiva Kumar

Recalling the 1980s, Bishnoi paints a stark contrast. “There were once herds of nearly 50,000 chinkaras roaming the desert,” he says. “Today, we hardly see 2,000, and they are vanishing before our eyes due to deteriorating ecological entities.” His modest facility in the heart of the Thar stands as a rare symbol of grassroots conservation where one man’s vigilance strives to keep Rajasthan’s wild spirit alive.

Silent Struggles

Yet, despite this reverence, the chinkara’s existence is increasingly precarious. Rapid habitat loss, unregulated grazing, wind farms, solar farms, and fast-expanding farmland are squeezing the open landscapes that the species depends on. Grasslands, often misclassified as “wastelands,” are vanishing under the plough or being converted into unregulated industrial zones.

Though the chinkara is listed as Least Concern by world standards, its numbers are declining rapidly in many pockets. In places where it once bounded freely, only scattered sightings remain, and even extinct in certain pockets in arid locations.

Hope on the Horizon

Despite these challenges, conservation efforts are slowly gaining ground. Protected areas such as Tal Chhapar Sanctuary (Rajasthan), Rollapadu Wildlife Sanctuary (Andhra Pradesh), and Nannaj Grasslands (Maharashtra) still offer refuge to this fleet-footed gazelle. Increasing awareness of the ecological importance of grasslands as carbon sinks, grazing reserves, and bird habitats has also begun to reshape conservation priorities.

For the chinkara, survival is not just about endurance; it’s about age-old harmony with landscape, culture, and community. As India reimagines its conservation strategies, this elegant gazelle could well become the flag-bearer for grassland protection, a reminder that dry regions and deserts, too, are full of life worth preserving.

Watching a chinkara sprint across a windswept plain is to witness freedom itself, a fleeting vision of wild grace untouched by time. In a world where wilderness is shrinking, the Indian gazelle remains a symbol of resilience and quiet beauty. If the tiger is the roar of India’s forests, the chinkara is its whisper, soft, swift, and enduring, echoing through the golden silence and resilience of the grasslands.

(The author is a wildlife writer and photographer)

Related News

-

Rewind: Pandavula Gutta — Telangana’s hidden gem of rugged rocks and ancient secrets

-

Rajasthan govt gives assurance no khejri tree will be cut illegally; Khejri Bachao Andolan called off

-

Rewind: Arrested on a screen — Inside India’s digital arrest fraud

-

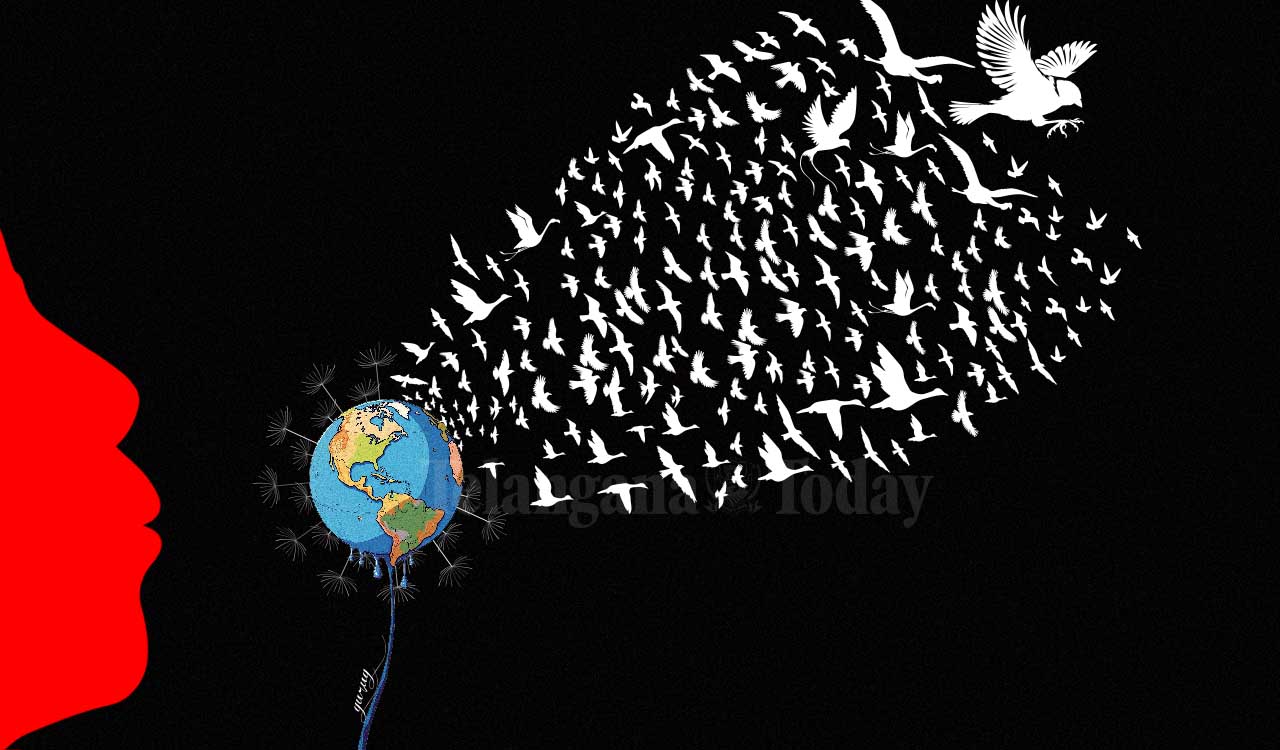

Rewind: Every bird counts — to protect them is to protect Earth

-

Hyderabad: Punjagutta Police arrest salesman for stealing 1 kg gold from Joyalukkas

1 min ago -

Supreme Court advises caution in pre-marital relationships

2 mins ago -

Delhi High Court grants temporary relief to Rajpal Yadav in cheque cases

6 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Cybercrime Police arrest three in Rs 19 crore USDT fraud

6 mins ago -

MBBS student from Bihar found hanging in Bengal hostel

11 mins ago -

UoH partners with MNJ Institute to advance personalised Cancer care

13 mins ago -

TN BJP chief challenges Vijay to spell out party policies

16 mins ago -

Osmania University to host AIU Central Zone Vice Chancellors’ Meet 2025–26

21 mins ago