Rewind: When the job guarantee disappears — how VB-GRAMG weakens women’s work rights

As the Union government replaces MGNREGA with centrally designed VB-GRAMG, it quietly dismantles a rights-based employment guarantee, putting rural women’s livelihoods at risk

By Ashraf Pulikkamath, Anjitha Gopi

For many rural women, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is more than just a government scheme. It is often the only reliable source of income they can access locally, predictably, and without having to negotiate with contractors, landlords, or male intermediaries. In our field engagements, women repeatedly described MGNREGA as their sole means of survival, given their limited social and economic privilege, weak bargaining power in labour markets, and constrained agency within families and communities.

Also Read

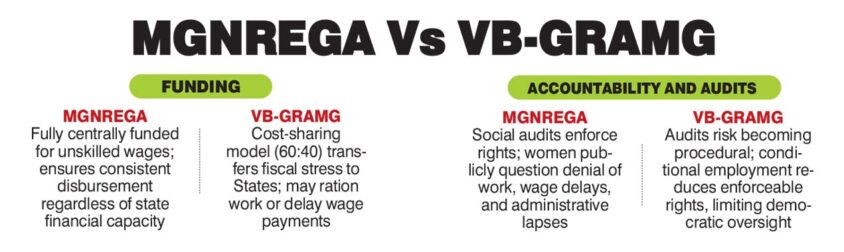

It is against this lived reality that the Union government’s proposal to replace MGNREGA with a new law, the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) or VB-GRAMG, must be examined. While official communication highlights an increase in guaranteed workdays from 100 to 125, media reports reveal that this numerical expansion is accompanied by a deeper restructuring of funding, governance, and entitlement.

Together, these changes alter the very character of the programme. What is being presented as reform increasingly resembles a shift from a rights-based employment guarantee to a centrally managed village programme.

MGNREGA and Women: A structural relationship

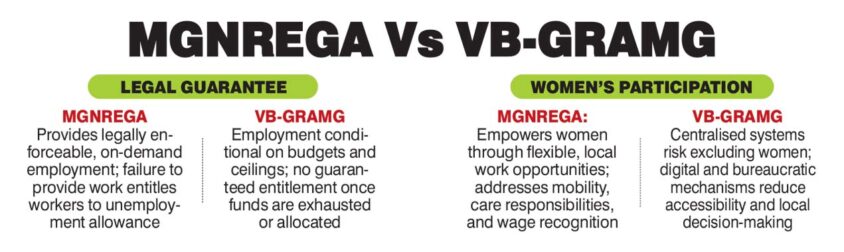

Women have consistently formed the backbone of MGNREGA. They account for nearly 60% of total person-days generated nationally, with States such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu recording women’s participation levels as high as 85% to 90%. This was not incidental. MGNREGA worked for women precisely because it recognised structural constraints such as limited mobility, unpaid care responsibilities, caste-based exclusion, and weak negotiating power in informal labour markets.

By guaranteeing wage employment close to home and on demand, MGNREGA functioned as both a social protection measure and a labour market correction. For Dalit and Adivasi women in particular, it offered rare recognition of their labour as paid work rather than invisible service. Crucially, this recognition was backed by law. If work was demanded and not provided, workers were entitled to an unemployment allowance. The guarantee was enforceable, not discretionary.

Policy Expansion on Paper, Erosion in Practice

VB-GRAMG replaces MGNREGA’s demand-driven architecture with pre-fixed, normative allocations determined annually by the Centre, alongside expenditure ceilings. Once these allocations are exhausted, the guarantee effectively ends.

This shift has far-reaching gendered consequences. Under MGNREGA, demand itself created a legal obligation on the State. Under VB-GRAMG, employment becomes conditional on budgets, ceilings, and administrative discretion. When funds run out, rights run out. For women workers who already face barriers in accessing local power structures, this dilution of justiciability disproportionately weakens their ability to claim work.

One Policy, Uneven Consequences

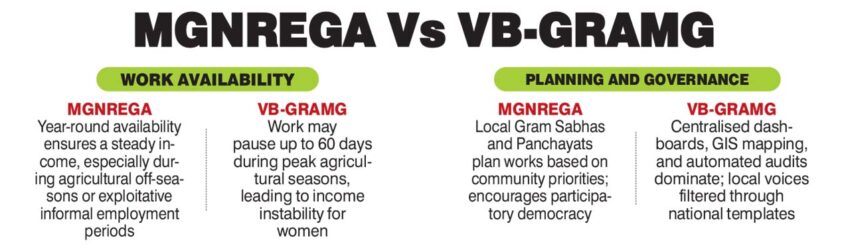

Another significant departure lies in work availability. The proposed framework mandates a suspension of public works for up to 60 days during peak agricultural seasons. This is justified as a measure to prevent labour shortages in farming. However, it rests on the assumption that rural workers are uniformly cultivators who can absorb income shocks during these periods.

For most women workers, this assumption does not hold. The majority do not own land. Agricultural seasons do not reduce their workload; they intensify unpaid care, subsistence, and household labour. MGNREGA’s year-round availability mattered precisely because it allowed women to smooth incomes when other work was unavailable or exploitative. A uniform seasonal pause does not operate neutrally. It redistributes risk onto women whose labour remains undervalued or entirely unrecognised during so-called peak seasons.

Fiscal Federalism and Shrinking of Guarantees

The fiscal restructuring is equally significant. The shift from 100% central funding of unskilled wages under MGNREGA to a 60:40 Centre–State cost-sharing model for most States under VB-GRAMG is framed as cooperative federalism. In practice, it transfers fiscal stress downward to State governments.

States with constrained finances may be compelled to ration workdays, delay wage payments, or quietly scale back implementation. Employment guarantees that primarily benefit women, especially poor, Dalit, and Adivasi women, are often the first to be compromised under such pressures. What was once a nationally backed right becomes contingent on State budgets and shifting political priorities.

Centralised Dashboards, Weakened Local Voice

VB-GRAMG also marks a governance shift. While MGNREGA entrusted Gram Sabhas and Panchayats with identifying works based on local needs, VB-GRAMG institutionalises centralised digital stacks, GIS mapping, dashboards, and automated audits. Local priorities are increasingly filtered through national templates.

For women workers, this transition is not merely technical. Digital exclusion, biometric failures, and weak grievance redress mechanisms have already been documented under existing welfare architectures. Making such systems statutory risks exclusion without appeal, reducing workers to data points rather than rights-bearing citizens. Decentralisation gives way to central control, even as implementation risks are devolved to states.

Social Audits without Enforceable Rights?

The new law promises stronger monitoring and transparency mechanisms. Yet the effectiveness of social audits, one of MGNREGA’s most significant democratic innovations, depends on the presence of enforceable rights.

Under MGNREGA, social audits created collective forums where workers, many of them women, could publicly question denial of work, delayed wages, and administrative lapses. These spaces mattered because the law recognised employment as an entitlement. Once employment itself becomes conditional and capped, social audits risk being reduced to procedural exercises, closer to financial audits than democratic accountability.

Field Realities

Over the past year, we have been studying MGNREGA’s impact on the ground across Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu through field engagements, worker interactions, and local-level observations. These regions, often cited as relatively better-performing States in terms of MGNREGA implementation and women’s participation, offer critical insight into what is at stake when the nature of the programme itself is altered.

Women we engaged with in Andhra Pradesh were unequivocal. MGNREGA is often the only form of work they can access without migration, indebtedness, or dependence on male intermediaries. Their limited negotiating power within households, labour markets, and village institutions means alternatives are either unavailable or deeply exploitative.

For these women, MGNREGA wages are not supplementary income. They are subsistence. Any dilution of the guarantee, therefore, has immediate consequences, pushing women back into economic dependence, unpaid labour, and informal work arrangements that offer neither security nor dignity.

What is Truly at Stake

Critics argue that VB-GRAMG removes the soul of a rights-based employment guarantee, replacing it with a centrally controlled, conditional scheme that shifts costs to States but allows the Centre to gain political recognition. From a gender perspective, this loss is particularly stark.

MGNREGA was not merely an asset-creation programme. It was an acknowledgement that employment itself is social protection, and that women’s labour deserves public remuneration backed by law. The move towards VB-GRAMG is, therefore, not just a policy redesign, but a reframing of rural labour, from a right to be claimed to a resource to be managed.

In this transition, women risk disappearing from policy imagination, from accountability mechanisms, and eventually from guaranteed paid work. Reclaiming MGNREGA’s original intent is not only a question of administrative design. It is a gender justice imperative.

As MGNREGA is recast from a legal right into a conditional programme, the question that remains is simple: who absorbs the risk when the guarantee disappears, and why is it almost always rural women?

(Dr Ashraf Pulikkamath and Dr Anjitha Gopi are Assistant Professors at Vellore Institute of Technology–Andhra Pradesh (VIT-AP) University, Amaravati. They are currently working on MNREGA’s impact in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu)

Related News

-

Lok Sabha proceedings adjourned till noon

3 mins ago -

Focus on subjects like AI, automation needs to be increased: PM Modi

7 mins ago -

No mass job cuts at Tech Mahindra, IT major clarifies

22 mins ago -

Bengal govt replies to MHA’s note on protocol violations during Prez Murmu’s visit

27 mins ago -

Surya, Samson and Abhishek reflect on faith, guidance and triumph after India’s T20 World Cup win

27 mins ago -

Petrol, diesel prices unlikely to be raised in near term amid supply disruption

36 mins ago -

Mojtaba Khamenei named Iran’s Supreme Leader

44 mins ago -

Six injured as RTC bus hits lorry on Rajiv Rahadari near Siddipet

45 mins ago