Rewind: Does Bandung legacy echo in Global South today?

The Bandung Conference, held in 1955 and which brought together leaders from 29 Asian and African nations, remains a powerful symbol of unity, non-alignment and the collective voice of the Global South

By Dr Akhil Kumar, Dr Anudeep Gujjeti

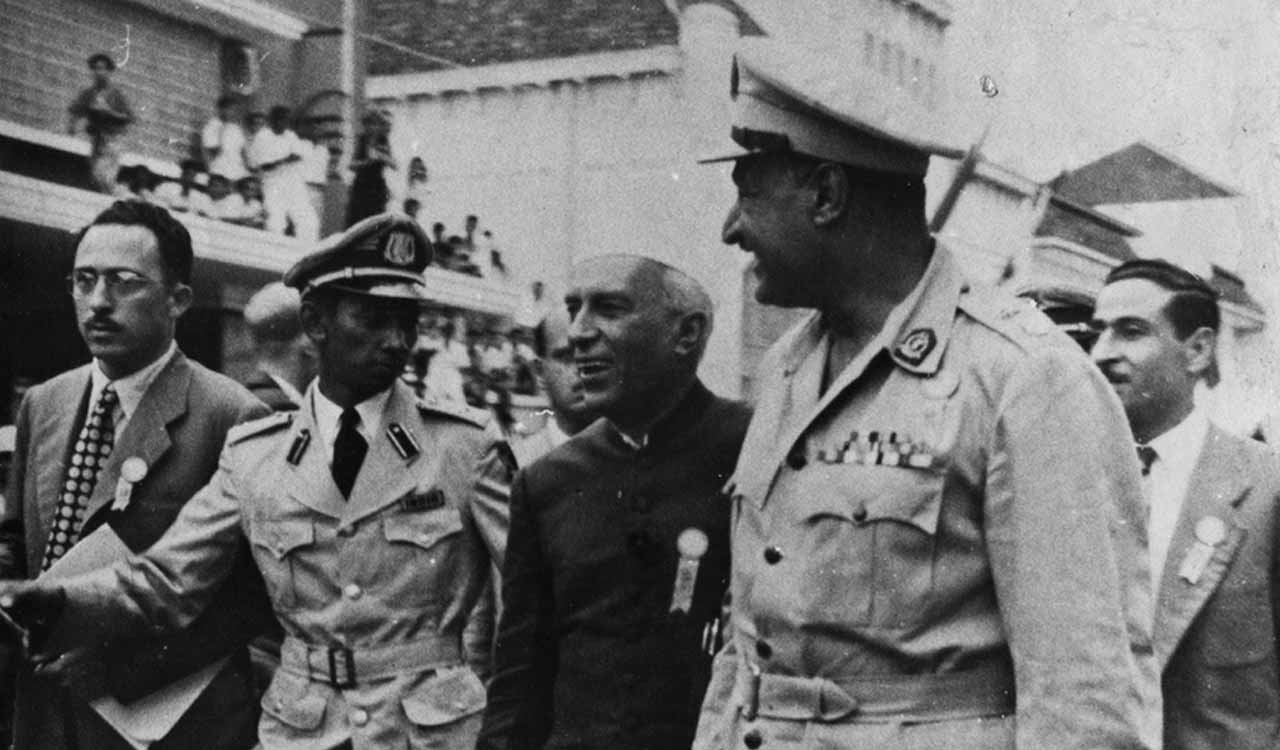

This April marked the 70th anniversary of the historic Bandung Conference, a pivotal moment in 20th-century diplomacy that reshaped the global geopolitical landscape. Held in April 1955, in the Indonesian city of Bandung, the conference brought together leaders from 29 Asian and African nations, many newly independent, to chart a course of solidarity, cooperation, and resistance against colonialism and Cold War pressures. As we reflect on its enduring legacy, the Bandung Conference remains a powerful symbol of unity, non-alignment and the collective voice of the Global South.

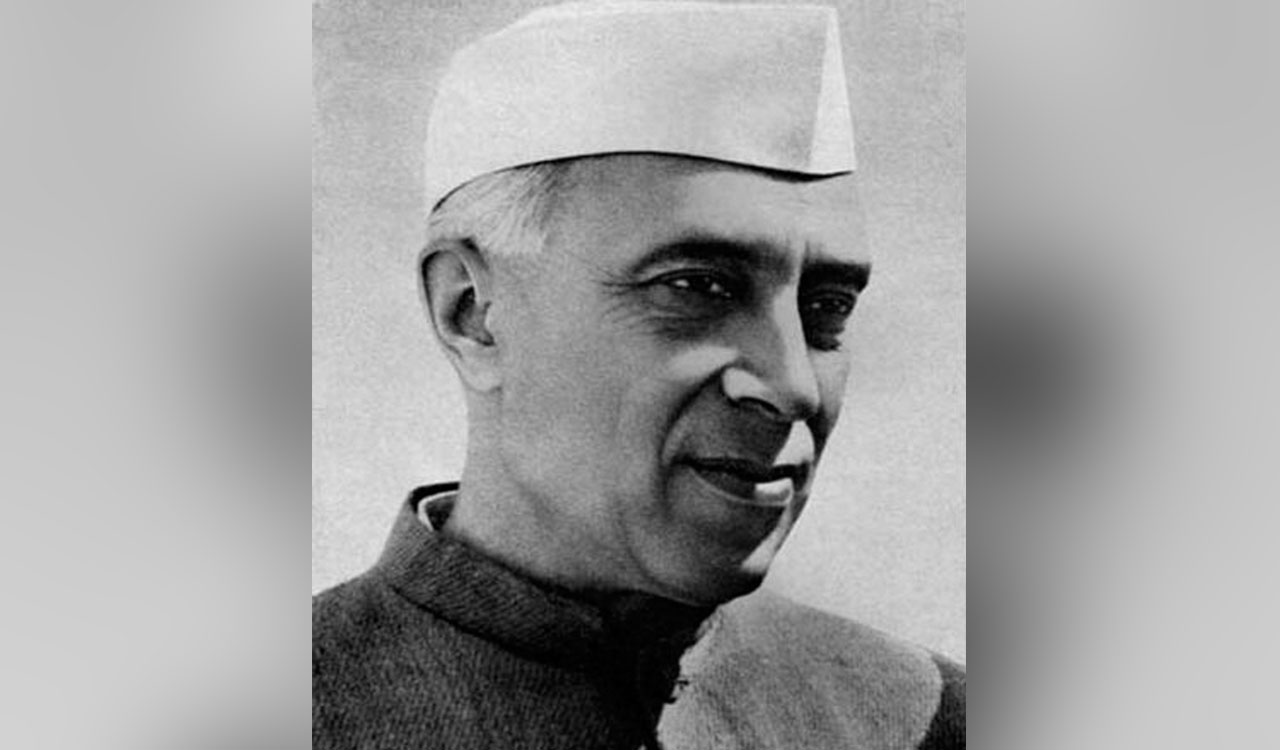

Following its independence in 1947, India, under Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister (he held both positions until his death in 1964), adopted the policy of ‘non-alignment’, which turned out to be its most imaginative contribution to world politics. In view of the emerging bipolar world order and its mounting tensions shaped by the Cold War, India deliberately chose to distance itself from the ideological and strategic rivalry between the two superpowers — the United States of America and the Soviet Union.

Birth of NAM

Interestingly, the idea of Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was born in 1961 as an offspring of the deliberations held during the Bandung Conference in 1955, spearheaded by five global leaders — Nehru (India), Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) and President Sukarno (Indonesia), distinct from the rivalrous power blocs led by the US and Soviet Union.

The Bandung Conference was the first major international conference in which communist China participated without the presence of the Soviet Union

Amidst the turbulence of the Cold War, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Nehru envisioned a distinct role for India, one where it would emerge not merely as a newly independent state, but as a moral and political force in Asian affairs. This was a pivotal moment in regional geopolitics. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Revolution ended, culminating in the rise of the People’s Republic of China, while India was grappling with the fresh scars of partition and the emergence of Pakistan as a separate nation.

Moreover, Nehru was concerned over US President Dwight D Eisenhower’s administration’s intent to provide military aid to Pakistan, a move formalised in May 1954 through the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement (MDAA), given its strained relationship with India. Nehru viewed this move by the US to significantly alter the balance of power in the sub-continent, although he wanted India to remain undeterred.

He perceived this not only as a direct threat to regional stability but also the risk of the sub-continent becoming a conflict zone for the superpower rivalry at a time when India was advocating for peaceful co-existence and championing Asian unity through its non-alignment policy.

The subsequent formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) in September 1954, comprising the US, United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Pakistan further entrenched Cold War bipolarity in Asia, intensifying Nehru’s apprehensions about the militarisation of Asian region through these defence pacts and the erosion of sovereign decision-making among newly independent states.

The suspicion of both India and China, the big powers of Asia, generated at Bandung paved the way for a regionalism of smaller nations to emerge in Asia. This was realised with the establishment of ASEAN in 1967

A key articulation of Nehru’s international relations philosophy appears in The Discovery of India, penned during his imprisonment in 1944. Under the section titled ‘Realism and Geopolitics: World Conquest or World Association?’, Nehru firmly resented the idea of regional security arrangements dominated by major powers, an idea then advocated by thinkers like Walter Lippmann. He criticised such frameworks as merely extending power politics on a global scale, warning that they could not realistically lead to lasting peace or genuine international cooperation. For Nehru, true global harmony required moving beyond spheres of influence and great power dominance.

Andrea Benvenuti, in his work on Nehru’s Bandung: Non-Alignment and Regional World Order in Indian Cold War Strategy mentions three key factors that shaped Nehru’s interest towards the Bandung Conference.

Firstly, he was deeply reluctant to embarrass Indonesia, a fellow Asian nation and co-host of the conference, reflecting his commitment to regional solidarity. Secondly, Nehru harboured serious concerns about American regional policy, particularly its interventionist tendencies and support for military alliances. Thirdly, he sought to strategically leverage Chinese endorsement of the principle of ‘peaceful coexistence’, aiming to create space for non-aligned diplomacy amidst superpower rivalry during the Cold War years.

The First Step

The seeds of the Bandung Conference were sown through a series of preliminary consultations held in Colombo (Ceylon) and Bogor (Indonesia), which served as initial precursors to the formal convening of Asian and African nations.

In April-May 1954, Ceylon’s Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala hosted an informal summit in Colombo, bringing together the South and Southeast Asian Prime Ministers of India, Indonesia, Burma (now Myanmar) and Pakistan. In response to the prevailing bipolarity of the international system, there was a growing impetus among postcolonial Asian states to institutionalise Afro-Asian cooperation. The leaders deliberated on the evolving global and regional order, emphasising the necessity of coordinated efforts in promoting economic development, cultural exchange, and political solidarity among newly independent nations.

The Bandung conference had two major lasting impacts on India’s foreign policy — it widened the rift between India and China and endured China-Pakistan relationship

At the Bandung Conference, Nehru assumed the mantle of pan-Asian leadership, often positioning himself as the spokesperson for a unified Asia. He envisioned a post-colonial Asia asserting its strategic autonomy, free from the entanglements of superpower politics. From this standpoint, he strongly denounced the US-led military alliances such as SEATO and CENTO that several Asian nations had voluntarily joined. Nehru viewed these blocs not as instruments of collective security, but as extensions of Cold War power politics that compromised national sovereignty and undermined regional solidarity.

In his memoir, ‘Milestones on My Journey’, Ali Sastroamidjojo, an Indonesian leader and diplomat, talking about the deliberations in the Colombo conference contended that the intensifying rivalry between the superpowers and the escalating tensions of the international system would inevitably lead both blocs to seek the strategic alignment of as many states as possible within their respective spheres of influence.

Such geopolitical manoeuvring, rooted under the guise of power politics, was seen as a harbinger of a potential resurgence of colonial domination whether in its historical manifestation or through more insidious, modern forms of political and economic control. This emerging threat, he argued, represented a shared challenge confronting all newly independent Asian and African nations.

Not India’s Baby

While the Bandung Conference is often associated with India’s leadership, the true credit for its inception lies with Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo. As Krishna Menon, Nehru’s trusted confidant, openly admitted, the Asian-African Conference was “not India’s baby.” Initially, Nehru exhibited limited enthusiasm when Sastroamidjojo floated the idea in April 1954. It moved at a slow, crawling pace, and India’s endorsement was far from guaranteed.

Yet, despite this early reluctance and inhibitions, the success of Bandung ultimately hinged on India’s considerable diplomatic heft. Indonesia, still finding its footing in the international arena, lacked the infrastructure and experience to convene a summit of such scale.

It was not until the latter half of 1954 that Nehru embraced this initiative, recognising its potential as a platform for promoting postcolonial solidarity and non-alignment amidst rising Cold War tensions. India’s eventual backing gave the conference both legitimacy and momentum, underscoring the complex interplay of leadership, influence, and pragmatism in shaping Global South diplomacy.

When the Colombo Powers convened in Bogor for their second preparatory meeting in December 1954, their primary objective was to discuss the agenda and formulate a basic framework for the Bandung Conference. Among the key deliberations was the formulation of criteria for participation, particularly the selection of Afro-Asian nations to be invited. Although it was unanimously decided in the meeting to extend an invitation to all countries in Asia and Africa, invitations to two countries, namely China and Israel, turned out to be controversial.

The China Factor

Initially, Nehru supported the inclusion of two nations, arguing that both are geographically located in the Asian continent and independent. At the same time, New Delhi viewed that the absence of China and Israel would make the Afro-Asian meeting incomplete. Beijing viewed that an opportunity for participation in the Bandung Conference would end its diplomatic isolation within the region by turning the tide in its favour. Of the 29 countries, 18 that attended the conference had not recognised China.

The Bandung Conference was the first major international conference in which communist China participated without the presence of the Soviet Union. The conference represented a pivotal juncture in the evolution of postcolonial internationalism, foregrounding not only solidarity among newly independent states but also the strategic contestation for normative and political leadership in Asia. The talks between Nehru and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai at Bandung, while outwardly collaborative, were underscored by a subtle yet discernible rivalry that would foreshadow deeper Sino-Indian tensions in the years to follow.

From a liberal internationalist standpoint, Nehru approached Bandung with the ambition of institutionalising a normative framework for non-alignment, envisioning India as the moral vanguard of decolonised Asia through his civilisational discourse and emphasis on Panchsheel.

Contrarily, Zhou Enlai’s diplomacy at Bandung was marked by strategic foresight and ideological restraint. Being cognizant of China’s diplomatic marginalisation and the suspicions it evoked among smaller Asian states, Zhou calibrated his messaging to foreground peaceful coexistence and sovereign equality. In doing so, he effectively neutralised apprehensions about Chinese revisionism while subtly contesting Nehru’s claim to pan-Asian leadership.

Interestingly, the idea of Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was born in 1961 as an offspring of the deliberations held during the Bandung Conference in 1955, spearheaded by five global leaders — Nehru (India), Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) and President Sukarno (Indonesia)

However, according to Amitav Acharya, a leading scholar in international relations, the real winner at Bandung was neither China nor India, but the future ASEAN. The suspicion of both India and China, the big powers of Asia, generated at Bandung paved the way for a regionalism of smaller nations to emerge in Asia, one that is led by none of the big powers. This was realised with the establishment of ASEAN in 1967. Most importantly, the Bandung Conference had two major lasting impacts on India’s foreign policy — it widened the rift between India and China and endured the China-Pakistan relationship.

The Israel Factor

Nehru initially advocated for Israel’s inclusion in the Bandung Conference but the Arab states’ boycott over the Jewish state representation led India to reassess its position. The Pakistani factor played a significant role in shaping India’s policy towards Israel.

Krishna Menon revealed in a conversation with scholar Michael Brecher that Nehru felt New Delhi could not afford to remain indifferent to Islamabad, as Pakistan enjoyed support from the West, and India could not risk alienating another potential ally. This geopolitical reality compelled India to reconsider its stance. Ultimately, Israel was excluded from the conference, while eight Arab nations—Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen were invited.

Nehru’s initial push for Israel’s participation reflected his ideological belief that all independent Asian nations should be included in the conference. However, India’s diplomatic priorities, influenced by its relations with Arab countries and the strategic calculus involving Pakistan, necessitated a compromise.

Is the spirit alive?

The end of the Cold War replaced bipolar rivalry with a multipolar global order, rendering NAM’s strategic utility increasingly ineffective. India’s diplomatic engagement reflects this evolution with Prime Minister Narendra Modi skipping three consecutive NAM summits. While India continues to project itself as a major supporter of NAM, the forum no longer anchors its foreign policy.

For India, non-alignment historically represented not passive neutrality, but a strategy to pursue an independent foreign policy and promote Afro-Asian solidarity amid Cold War bipolarity. With the Cold War’s culmination and the easing of East-West tensions, India recalibrated its external engagements such as strengthening economic and technological ties with the United States, cautiously engaging a rising China, and deepening regional partnerships. In 2019, speaking about the NAM, External Affairs Minister Dr S Jaishankar said it was a concept shaped by “a specific era and a particular context.”

India has not entirely abandoned the spirit of Bandung. It continues to uphold strategic autonomy and positions itself as a voice for the collective interests of the developing world. Once emblematic of Global South solidarity, NAM has been overshadowed by more agile, issue-specific mini-lateral frameworks. India now engages in several multilateral groupings to address challenges like climate change, disaster resilience and food security. It is a founding member of BRICS, and participates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the G20 and newer platforms like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad).

Dr Jaishankar has articulated this act candidly by saying, “This is a time for us to engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbours in, extend the neighbourhood, and expand traditional constituencies of support.”

Since the Bandung Conference, much has changed on the global stage and within Indian domestic politics. However, the spirit of the Bandung Conference such as anti-hegemony, solidarity with the Global South, and sovereign equality continues to inform India’s worldview, even as forums and strategies have evolved.

(Dr Akhil Kumar is a PhD from Department of Political Science, University of Hyderabad. Dr Anudeep Gujjeti is Assistant Professor, Centre of Excellence for Geopolitics and International Studies REVA University, Bengaluru, and Young Leader, Pacific Forum, USA)

Related News

-

Nehru told Congress MPs they were not bound by whip in 1954 Speaker debate

-

Rewind: Pandavula Gutta — Telangana’s hidden gem of rugged rocks and ancient secrets

-

Komatireddy Rajgopal Reddy attacks Revanth Reddy again over claim to continue as CM

-

Rewind: Arrested on a screen — Inside India’s digital arrest fraud

-

Women councillors allege misconduct by Congress in Kyathanpalli

5 mins ago -

Gauhati Medical College doctor lodges FIR alleging harassment by principal

14 mins ago -

Two FIRs filed in Chikkamagaluru after week-long stone pelting on house

15 mins ago -

Viral video shows SUV hitting biker in Dwarka, teenage driver detained

17 mins ago -

Quadric IT returns to BioAsia with assistive mobility device for visually impaired

17 mins ago -

Thennarasu presents Tamil Nadu interim budget with focus on welfare and culture

19 mins ago -

Hyderabad CP inspects security at Mecca Masjid ahead of Ramzan

25 mins ago -

Opinion: Beyond the 72-hour workweek

25 mins ago