Rewind: Our future in a Vault

The 25th anniversary of England’s Kew Millennium Seed Bank gives us the opportunity to see how humanity future proofs the planet — from agriculture to culture

By Pramod K Nayar

Dystopian fiction and film often portray the future as forcing a return to the land, and older practices of hunter-gatherer and agriculture in the face of a toxified earth and water, and resultant food shortages. In a fact stranger than fiction, however, a mode of future proofing was inaugurated in 2008, anticipating food shortages, the impossibility of agriculture in the wake of a planetary catastrophe, and which opens up numerous queries and concerns.

Also Read

But future agriculture is also an exercise in memory, a battle against perishability.

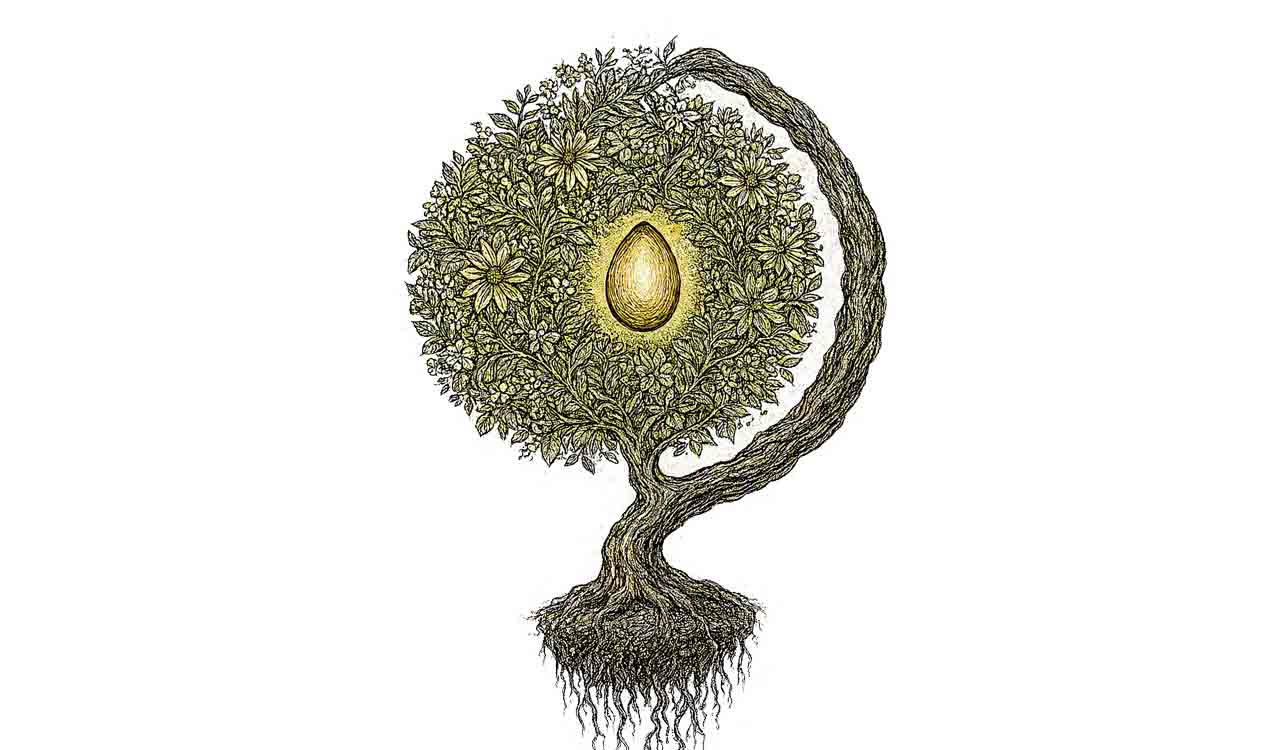

Planting Futures

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault was set up inside a mountain, on a Norwegian island approximately 800 miles from the North Pole. Nicknamed the ‘Doomsday Vault’, the vault is 130 metres above sea level and is, therefore, safe from any future rise of the water levels. It is located inside a geologically stable terrain and a consistently cold environment.

India has its own seed vault in Ladakh, set up in the 1980s. The Ukrainian vault, it is believed, has been partly destroyed in the Russian invasion. There are similar vaults around the world: Australia, France, and the USA. England’s Kew Millennium Seed Bank (MSB)— now celebrating its Silver Jubilee — has stored 2.5 billion seeds from more than 40,000 different plant species. As the project description puts it:

We’re also looking to the future.

Today, the MSB is more important than ever … where disasters such as wildfires and diseases have destroyed forests and other habitats.

Biobanking is the human race’s insurance against the future, when cryopreserved seeds will enable the regeneration of food crops. The then Norwegian Minister of Agriculture and Food Lars Peder Brekk put it bluntly: “No one knows if the Seed Vault ever will be needed. No one knows if and when the seeds will be sent back to their depositor to restore a seed collection that has been lost. That’s how insurance policies work.”

Biobanking is a global insurance policy against the extinction possibilities of much of mankind and other species — from plants to creatures

Moral Obligation, via Hi-tech

David Attenborough referred to the MSB as ‘perhaps the most significant conservation initiative ever’, thus pointing to the future values driving the biobanking project. Future proofing appears to be the fulfilment of a promise and a moral obligation to future generations. In fact, it begins with the acknowledgement that we in the present must ensure continuity.

Moral obligation of this kind, then, presupposes human continuity. It lends the term ‘sustainability’ a very clear temporal dimension. Indeed, as early as the Brundtland Commission Report titled Our Common Future (1987) described it,

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

We need to create burial sites, sarcophagi, interment sites today so as to ensure humans will be able to (re)turn to agriculture in the aftermath of a catastrophe. These cultural practices are no different from the Seed Vaults, because these are also human attempts at battling perishability of memory and identity.

Conservation seeks to extend a timeline, even if frozen, far into the future where biodiversity loss is seen as inevitable but not irreversible. In this, the biobanking projects come close to the rewilding projects to bring back the woolly mammoth and other extinct species in a cultural fable inaugurated by Jurassic Park.

Biobanking is an example of the merger of capitalism, science and high-tech. Sustainability is the cumulative effect of a network of human and non-human entities (seeds) and processes (cryogenic preservation), all of which are heavily funded. Moral obligation, clearly, is a capital-heavy ideal.

Even if the future citizen opts for low-trophic lifestyle with minimal consumption, as the Blue Humanities-posthumanist scholar, Cecilia Åsberg and others have called for, the merger of hi-tech and capital is integral to this renewed moral lifestyle. The novelist Kim Stanley Robinson has drawn attention to this merger. In his The Ministry for the Future (2020), Robinson fictionalises the costs of saving the southern seas as follows:

the amount of electrical power needed to pump that much water up onto the east Antarctic ice cap came to about seven percent of all the electricity generated by all of global civilization.

And elsewhere in the novel, a scientist offers statistics from largescale geoengineering projects needed to save the earth:

Building the infrastructure to do that would not be feasible. And it would have to be clean energy pumping it, or you’d be emitting more carbon. That much clean energy would take ten million windmills …

To save the earth, you need to exhaust the earth!

Knowledge Arks

A parallel project in future proofing is the Knowledge Ark. Built on the assumption that, in the event of a catastrophe that destroys much of the planet and human life, valuable information would be lost to the survivors (with the collapse of, for example, the www). Knowledge Arks are ambitious projects on earth as well as in space, projected to store not just information for the race’s survivors, but also any information that future generations may need. This includes libraries, from books to pictures, the seed vault of course, and other materials. Taking its cue from the Biblical Ark, Knowledge Arks are seen as the cornerstone of a post-apocalyptic world.

Given the unequal impact of climate change on the First and Third Worlds, to say that both should be equally responsible in addressing the crisis is unfair. The resistance from the latter about such an unfair demand is likely to produce climate sovereignty as an ideology

The Memory of Mankind project, inaugurated in 2012 in Austria, is such an Ark, often called a time capsule of the modern world. The Arch Mission Foundation in 2019 tried setting up a Lunar Library of 30 million pages, designed to survive for millions of years in space — the spacecraft crash landed, and the fate of the collection is not clear yet. The UNESCO Memory of the World project is also, on similar lines, founded on the idea that humanity’s memories are worth preserving.

Future Climate Sovereignty

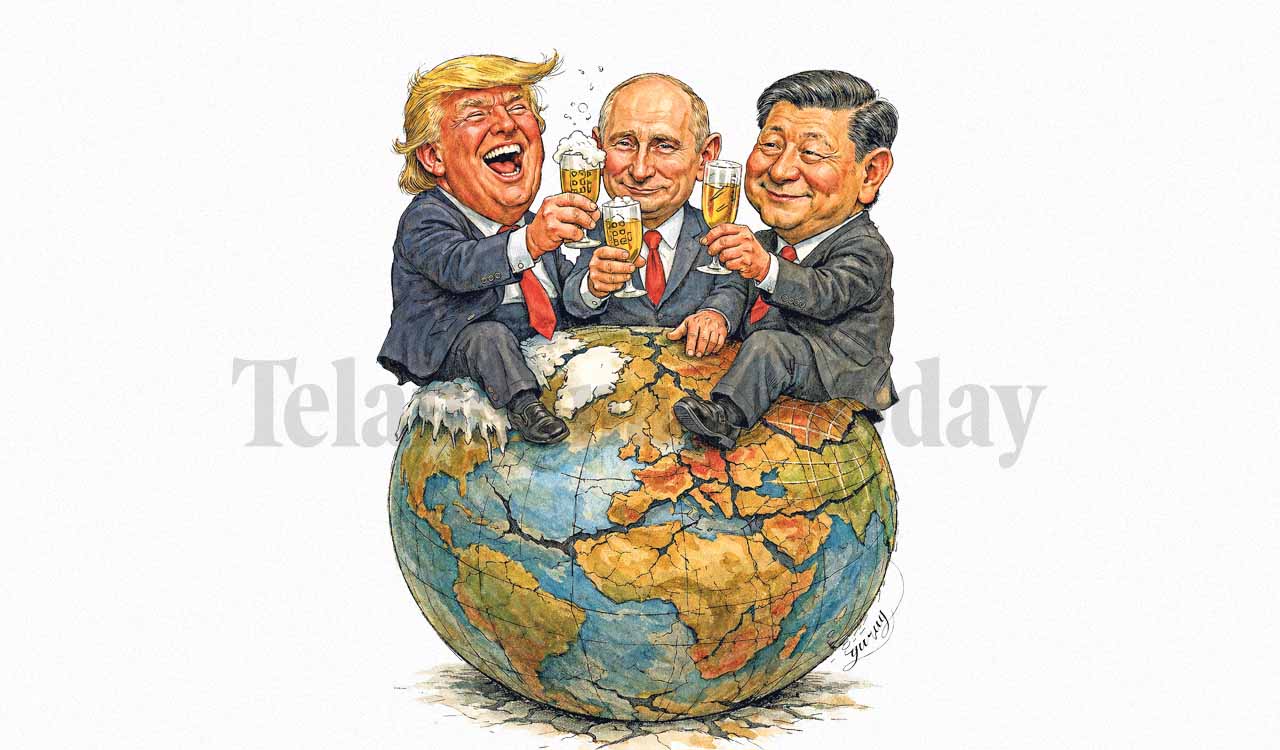

Future proofing also demands common-cause building among nations. Given the acrimonious deliberations that we see at the COP, the withdrawal of superpowers from climate agreements, the unequal parcelling out of responsibility to save the earth among the countries least contributing to the earth’s toxification, how does biobanking work? Would all nations, including those unable to contribute to a vault, be entitled to the seeds? What does the future of such consensual disaster-proofing look like?

Biobanking projects are themselves cultural fables and an imaginative negotiation with a problematic experience, in this case, the anticipation of such an experience — of disaster. Integral to such cultural fabulationis the imagining of the exact opposite of such solidarity: the rise of climate sovereignty in the future.

Once again, Kim Stanley Robinson anticipates this moment in The Ministry for the Future. In the novel, India opts out of the ‘Paris Agreement’ to protect itself from drastic climate change. The Indian bureaucrat tells the Ministry officials:

We won’t allow another heat wave just so we can be in compliance with a treaty written up by developed nations outside of tropics and their dangers.

Robinson describes a whole new paradigm emerging:

Best soil and climate on Earth. Now banking 7 parts per thousand of carbon per year, immense drawdown. Also food for millions. Local tenure rights for local farmers, no absent landlords anymore except for India herself. Stewards of land. Keep room for wild animals in the hedgerows and habitat corridors. Tigers back, dangerous but beautiful. Gods among us. And all organic. No pesticides at all. Sikkim model now applied to ag all over India.

Robinson’s chapter on India’s newly found techno-capitalist-national identity concludes with a series of observations of a vastly altered eco-political frame:

No outsider gets to tell India what to do, not anymore. Never again. Post-colonial anger? Post-geoengineering defensiveness? Tired of the Western world condescending to India? All of the above?

Here Robinson foregrounds global capital and racial-political inequalities that underwrite international treaties and produce unequal impact of climate crisis. Although the ‘local’ is no longer separable from the global — ocean currents, air currents and wind- and water-borne chemicals penetrate the remotest parts of the planet — local modes of thinking about identity will intervene in any such project.

Cultural fables of biobanking as future proofing would do well to accommodate fables of climate sovereignty too.

Thwarting Perishability, a fantasy

In all these projects, a future life for the earth is wished into existence but can we determine how the future race will live? The fear of perishability drives us to invent technologies like the Seed Vaults, projects to preserve memories and thus thwart complete erasure. Philosophically, this is an attempt at continuity, to prevent the complete disruption of human culture which, we believe, is worth remembering and even repeating in the aftermath of the apocalypse.

Preserving knowledge of and for humans for a post-apocalyptic planet has resulted in Knowledge Arks— vast libraries of information designed to survive for millions of years

We could think of these vaults as the biotech equivalent of the arts. The arts, from painting of still life to biographies, have always been obsessed with perishability. Immortalising the beloved, the world, oneself in rhyme, visuals or prose has been one of the oldest of human projects.

The ‘carpe diem’ (‘seize the day’) motif in literature is an attempt to live life fully in the moments available to us, assuming the perishability of all life. One of the oldest expressions of this perishability anxiety belongs to the ancient Roman poet Horace:

Scale back your long hopes

to a short period. While we

speak, time is envious and

is running away from us.

Seize the day, trusting

little in the future.

The English poet Robert Herrick wrote:

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today

Tomorrow will be dying.

One of its most famous expressions is the poet Andrew Marvell’s lines in ‘To His Coy Mistress’:

Now let us sport us while we may,

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour

Than languish in his slow-chapt power.

The ‘mutability theme’ too is about the inevitability of decay and destruction. Cryopreservation may be a new tech, but preservation-against-perishability is as old as humanity. The arts fix the present for the future.

However, it is impossible to think and speculate how these Knowledge Arks and libraries for the future may be consumed by generations to come. How will anyone in AD 2500 interpret Horace, the scriptures, rock music, and surrealist painting? What is the afterlife of human narratives for the future humans?

These Arks are ways of defining us in the present, built on the assumption that a few humans will survive the end-of-the-world, and will want to continue life, and want memories of their ancestors.

Yet, interpretations cannot be governed. The response of a future generation may not be a responsible one. It is not always possible to impose modes of reading for the future that would be faithful to our ways of reading and writing. But then, why should the future be limited to our ways of thinking? For, to be irresponsible to these ways may actually be necessary to evolve new ways.

To perish is also to free the future from our constraints, whether these are seeds or words. Perishability is fought with future proofing but with no certainty that the future will make sense of what it inherits: it is the ultimate uncertainty with which mankind attempts to freeze our lives and thoughts for the heirs we imagine will come. As the philosopher Jacques Derrida said in his final interview a few months prior to his anticipated death from incurable cancer:

Each time I let something go, each time some trace leaves me, ‘proceeds’ from me unable to be reappropriated, I live my death in writing.

It’s the ultimate test: one expropriates oneself without knowing exactly who is being entrusted with what is left behind. Who is going to inherit, and how? Will there even be any heirs?

Will there be any heirs? Should there be?

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Kharge slams AI Summit management, alleges global embarrassment

12 mins ago -

PM Modi calls India AI Impact Expo 2026 powerful convergence

17 mins ago -

Writing code will not be main goal in AI era: Infosys Chairman

24 mins ago -

India contributes 16 per cent of world AI talent, white paper reveals

28 mins ago -

Kukatpally family conducts funeral after days of prayers for deceased

57 mins ago -

Hyderabad-based startup to begin human clinical trials for India’s first AI-driven antibiotic

1 hour ago -

Hyderabad: Mega job fair on February 23 at Red Rose Function Hall

1 hour ago -

Three engineering students arrested again for drug peddling in Warangal

2 hours ago