Rewind: The Dark Knight lasts long enough … for Madness

Arkham Asylum, 35 years later, remains a classic work in the Dark Knight oeuvre, principally for its theme: madness.

By Pramod K Nayar

What are the colours of a soul’s rage or madness? What if the soul is a very dark one, darker than the night? 35 years ago, a writer-artist duo set out to explore the answers.

Erich Fromm, philosopher and psychologist, stated in his book The Sane Society (1955):

Nothing is more common than the idea that we, the people living in the Western world of the twentieth century, are eminently sane. … We are sure that by introducing better methods of mental hygiene we shall improve still further the state of our mental health, and as far as individual mental disturbances are concerned, we look at them as strictly individual incidents.

Fromm asks:

Can we be so sure that we are not deceiving ourselves? Many an inmate of an insane asylum is convinced that everybody else is crazy, except himself.

Fromm’s question finds its odd resonance in the Joker’s repeated insinuations about the nature of his madness. And Batman’s. Determining the nature of madness is a difficult task, as Fromm and the Joker agree, and painters from Francisco Goya to Salvador Dali agree.

A brilliant writer-artist duo decided that one way to map the cracking-up of a tormented soul was to place it within a place where madness reigns. Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989) celebrates 35 years of mind-bending brilliance in its mapping of the Dark Knight’s great test: in the heart of the Asylum that houses his most powerful enemies.

Scene of the Grime

Taking its title from Philip Larkin’s amazing poem, ‘Church Going’, Arkham Asylum leads us into the grime that inhabits the human mind. We first get the history of the notorious asylum. Amadeus Arkham sees his mother descend into madness and her eventual suicide in their family home, Arkham. In his home, he records that ‘he felt little more than a ghost, haunting its corridors…inside the melancholy walls’. Decades later, when Arkham and his family come to stay, his daughter has nightmares. Tragedy strikes when an old patient of Arkham’s, Martin ‘Mad Dog’ Hawkins, murders and mutilates Arkham’s wife and daughter. Arkham then converts his home into an asylum. His aim is to exorcise the home of his childhood torments, to ‘set above it all an image of the triumph of reason over the irrational’. Arkham descends into madness too, and is incarcerated in his own asylum. In the contemporary, Batman is summoned to Arkham because the inmates, led by the Joker, have seized control. Batman encounters his old enemies, battles them and loses the grip on his mind.

In Arkham Asylum, the focus is the unstable, demented home for the criminally insane (the only one missing from this home is Hannibal Lecter). Morrison and McKean shift the focus away from the city and literally bring the madness home. Then, transforming the family home, with all its resident madness, into an asylum is a master stroke, and recalls the mad-woman-in-the-attic trope of Victorian fiction. It also inverts the image of the happy, secure family home: even as a child, Arkham never felt himself more than a ghost in his home. In other words, the small-scale madness of a family home erupts into the large-scale madness of an asylum.

Arkham becomes the home for tormented souls. The residents change, the terms of residency do not. Madness, derangement, violent tendencies are a prerequisite to reside therein, even if the resident is the owner himself. Here, Morrison’s citing of Lewis Carroll is pitch-perfect:

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here”.

If you are mad, you fit Arkham. Anyone inside Arkham has to be, by default, insane. This principle applies equally to the Joker, the doctors and in the final instance, to Batman too.

Like a home with its routine, an asylum also has its rules. But when the Joker takes charge of this scene of the grime, no rules apply and the ‘feast of fools’, as he calls it, begins, with torture, murder and mayhem. The inmates set up a game in which Batman is allotted one hour to hide. But later, the Joker at the instance of the rest, says, let’s hunt Batman down, let’s pretend the one hour is up. Critics Sarah K Donovan and Nicholas P Richardson in their essay, ‘Under the Mask: How Any Person Can Become Batman’ in the volume Batman and Philosophy, write:

The Joker lays out the rules for Batman when he is in the asylum, giving him one hour to hide, and Batman follows this arbitrary rule…following rules leads to the construction of a person’s identity.

But this is precisely the point Morrison makes: rules do not apply when the Joker is in power. The absurdity lies in Batman assuming that the Joker who set the rule of an hour, will abide by his own rules — this indicates Batman’s own loss of judgement, he who knows the Joker intimately takes the latter at his word.

Myth, Magic, Madness

Morrison-McKean build on the Dark Knight mythos in interesting ways. Nicholas Galante in his essay for the volume Grant Morrison and the Superhero Renaissance notes that Morrison has acknowledged influences such as the tarot, religious mysticism, quantum physics, surrealism, Lewis Carroll and Carl Jung. Madness and myth are intertwined, and produce the potent symbolism of Dave McKean’s art. Galante proposes that Morrison lays ‘a heavy emphasis on Batman’s perpetual renewal through the cycle of life, death, and rebirth’ (in Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Batman returns during a storm and when the first showers drench him, he declares that he is born again).

The bat, expectedly, is a constant symbol, first for Arkham’s mother, and later for others. Dr Charles Cavendish loses his stability when he reads Amadeus Arkham’s journal. Thus, a textual source of derangement is provided for Cavendish, and so he forces Batman too to read passages from the journal in which he speaks of a bat. He accuses Batman of supplying the ‘mad souls’ to this ‘hungry house’. Cavendish says: ‘I’m not fooled by that cheap disguise. I know what you are’. Not who, it may be noted, but what. Shamanism, symbolism, mysticism all partake of and are instrumental in the creation of Arkham’s inmates and their states of mind.

In Arkham Asylum, Ruth Adams the psychiatrist analyses the Joker as follows:

It’s quite possible we may actually be looking at some kind of super-sanity here. A brilliant new modification of human perception, more suited to urban life at the end of the twentieth century … Unlike you and I, the Joker seems to have no control over the sensory information he’s receiving from the outside world … He can only cope with that chaotic barrage of input by going with the flow … He has no real personality…He creates himself each day. He sees himself as the lord of misrule, and the world as a theatre of the absurd.

Batman himself, as the Joker reminds him, is not fully sane:

We want you in here. With us. In the madhouse. Where you belong.

The Batman admits:

I’m afraid.

I’m afraid that the Joker may be right about me.

Sometimes … I question the rationality of my actions.

When Batman calls the Joker a ‘filthy degenerate’, the Joker responds:

Flattery will get you nowhere.

You’re in the real world now and the lunatics have taken over the asylum.

We watch Batman unable to cope — he cannot fight off a scrawny Cavendish, and at one point stabs himself in his palm with a shard, giving himself a serious injury. Myth, magic and madness all converge in Arkham, and in Batman.

Drawing (Upon) Madness

A large part of the attraction of Arkham Asylum is Dave McKean’s artwork. With obvious influences of artists like the European surrealists McKean’s makes astonishing use of colours, shapes, shades, myths and symbols.

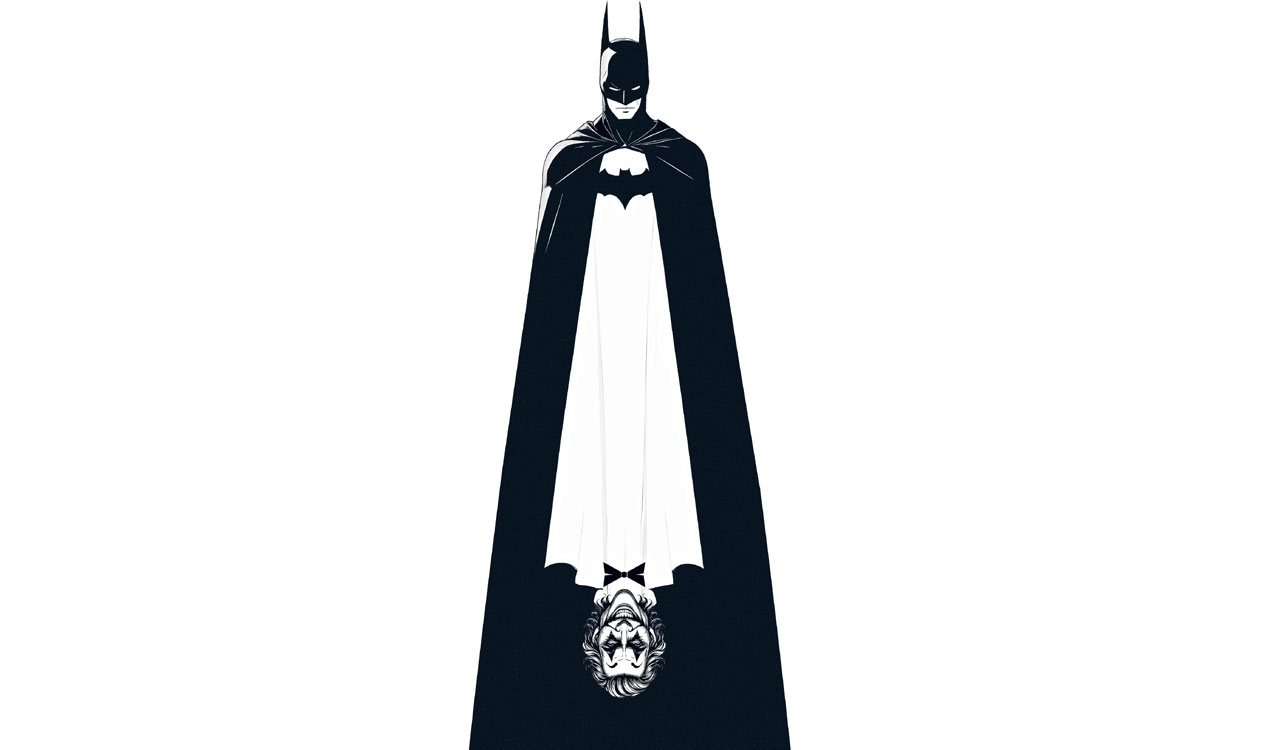

The drawing constantly harps on the irrationality of Batman which sits, in the tale, quite comfortably beside the Joker’s through images of reflection and mirrors. The Mad Hatter tells Batman: Arkham is a ‘looking glass’. The image shows Batman seeing his own reflection in the glass, and the Hatter declares: ‘And we are you’. Here Morrison is returning to an old Batman motif of mirrors, doubles and reflections. We see it in The Dark Knight Returns where Batman says that when he looks at Harvey Dent/Two-Face he sees a ‘reflection’. At the end of Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, the shadows of Batman and the Joker merge in a pool of water, again suggesting that Batman is not dissimilar to the supposedly mad villains. In Arkham Asylum, Batman says to himself:’ I must see my own reflection to prove I still exist!’

As his very being breaks down, Batman thinks, that he is ‘no longer able to tell where the dragon ended. And I began’. In all these images, McKean draws Batman as ghostly. The absence of definition enables us to recognise that he is losing cohesion. In the scenes where Batman cuts himself and Ruth Adams slashes Cavendish’s throat splatters of red that bleed, literally, across the page/panel.

The most powerful drawing in the work is the scene when Arkham discovers his dead wife and child. He finds first his wife and then his decapitated daughter’s body. He looks for Harriet’s head, and finds it in the dollhouse. The text reads:

And then I look at the doll’s house.

And…the…doll’s…house…looks…at…me.

Recalling Nietzsche’s famous aphorism about looking into the abyss, McKean’s drawing shows a large panel followed by smaller panels, with the daughter’s face in them. The panels become smaller. They are arranged in vertical strips (of the glass panes of the dollhouse), indicative of Arkham’s mind being stripped down. One staring eye is his own, and looking back at him are the eyes, and then the single eye, of his beheaded and violated daughter. In the background is the sound of the cuckoo clock that, unmindful of the horror around it, chimes the hour, ‘cu-koo’, also referencing the slang term for madness, ‘cuckoo’. The dollhouse and the dead daughter’s eye look back and reflect his own.

Other symbols of madness also pervade the text: the insect that Arkham’s mother appears, to Arkham, to eat. There are bats, of course. The lettering is customised to indicate madness. Batman’s words are in white letters in a black balloon, the Joker’s is red and pointy but not inside a balloon. While Batman’s words/letters are circumscribed inside frames symbolic of a minimal respect for rules, the Joker’s are not – indicating that he is not bound or limited in any way.

The house clock figures throughout the tale, appearing in various guises. Clocking the time of the descent into madness, it also recalls, alongside Carroll and Larkin, the famous lines from Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘On Visiting St Elizabeth’s’, a poem about visiting the poet Ezra Pound in an asylum:

This is the time

of the tragic man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.

This is a wristwatch

telling the time

of the talkative man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.

This is a sailor

wearing the watch

that tells the time

of the honored man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.

On one wall of Arkham Asylum is a slogan, ‘Discover thyself’, written in Greek and in childish script. This slogan is the governing motif of the book. Batman discovers himself, and he does not like what he has found. That is, what Arkham Asylum reveals to Batman is that he too belongs in there: he is a mirror image of those locked up.

That is why the Joker asks Batman:

Have you come to claim your kingly robes? Or do you just want us to put you out of your misery, like the poor sick creature you are?

In one of the final pages, Two-Face’s coin is tossed up to decide Batman’s fate, and this is drawn as a silver circle rising and falling in a series of black and one blue, lightning-streaked panel. The coin resembles the moon, of course, symbolic of moon-madness. The toss is in Batman’s favour and he walks free. Which is when the Joker, grinning as usual, says:

Enjoy yourself out there.

In the asylum.

Just don’t forget…

If it ever gets tough…

There’s always a place for you here.

Unmatched except by Alan Moore-Brian Bolland’s Batman: The Killing Joke (where the Joker famously says, ‘All it takes is one bad day to reduce the sanest man alive to lunacy. That’s how far the world is from where I am. Just one bad day’). Arkham Asylum, 35 years later, remains a classic work in the Dark Knight oeuvre, principally for this very theme: madness.

Perhaps, as Arkham Asylum says of the Joker, there is a super-sanity.

Perhaps not everyone descends into madness.

Perhaps some, like a very Dark Knight, rise into it.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Kashmiri students allege hijab, ramzan restrictions at Kurnool nursing college

6 mins ago -

Fraudsters posing as Mumbai ATS officials cheat Hyderabad senior citizen

37 mins ago -

Cyberabad police launch intensified ‘visible policing’ drive across Commissionerate

39 mins ago -

Know About NCB Calculation During Car Insurance Renewal

41 mins ago -

Security forces open fire at drone along LoC in J&K’s Poonch sector

49 mins ago -

Justice will prevail: KTR reacts to court verdict in alleged liquor scam

55 mins ago -

The One India Advantage — How BINDZ Consulting Is Building a Borderless Talent Organisation

56 mins ago -

Adilabad farmers seek KCR’s rule in Telangana again

1 hour ago