Rewind: The great mineral rush — can India break free from its critical mineral dependence?

As nations scramble for lithium, cobalt, and rare earths, India must build its own 'Mineral Manhattan Project' to secure its clean-energy future

By Dr Jadhav Chakradhar, Dr Mini Thomas P

In a world racing toward net-zero carbon emissions, critical minerals such as lithium for batteries, cobalt for electric vehicles, and rare earths for wind turbines have become the lifeblood of the green transition. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), as of November 2025, global demand for these mineral resources is projected to quadruple by 2040.

The rapid global shift to electric mobility is a significant driver of demand. Electric car sales reached nearly 14 million in 2023 — up 35 per cent from 2022 and more than six times the 2018 level. China, Europe, and the United States accounted for 95 per cent of these sales, with China alone selling 8.1 million EVs, Europe over 3 million, and the US 1.4 million. Emerging markets are also accelerating, with India experiencing a 70 per cent growth and Thailand quadrupling its sales. This electrification surge is sharply increasing demand for lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earths used in batteries and powertrains, particularly as China’s market expands through the adoption of PHEVs (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles), EREVs (Extended-Range Electric Vehicles), and larger battery packs that require more minerals per vehicle.

China’s Dominance

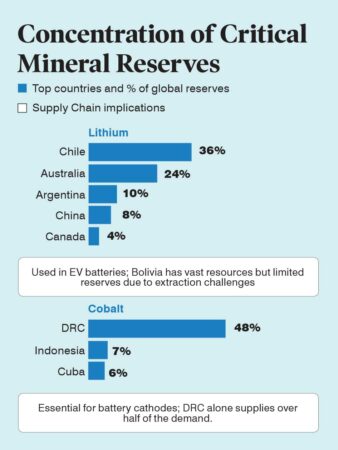

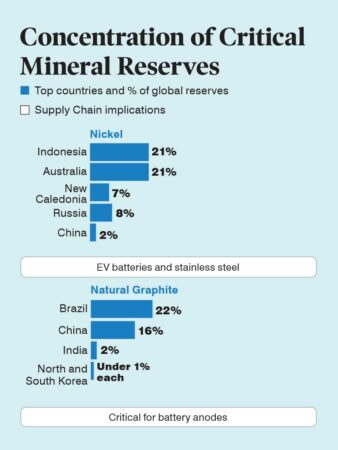

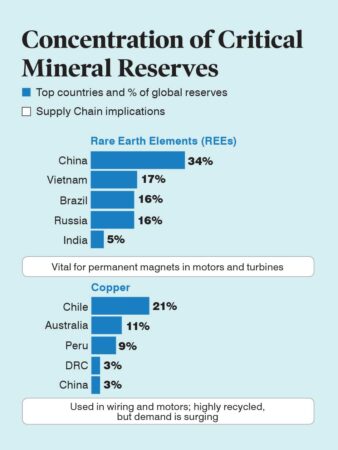

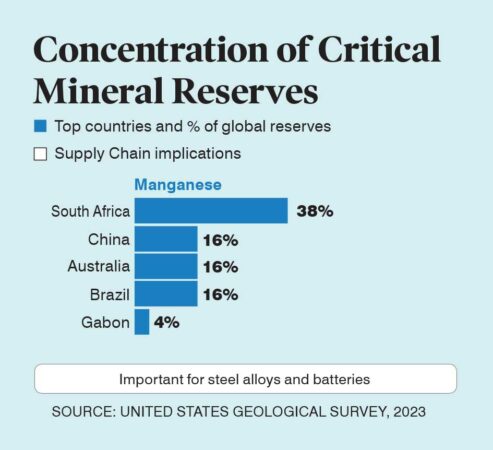

The energy transition to low-carbon technologies, such as electric vehicles, wind turbines, and solar panels, relies heavily on critical minerals essential for batteries, magnets, wiring, and other components. However, supply remains highly concentrated geographically, creating risks for global supply chains. Based on 2023 USGS data, reserves are unevenly distributed, with a few countries accounting for a significant portion.

China dominates across multiple minerals (eg, rare earth elements [REEs], graphite, and manganese), holding approximately 34 per cent of REE reserves. Australia leads in lithium, nickel, and manganese production, while Chile controls a significant portion of the world’s lithium and copper supply. Other key players include Brazil (graphite, REEs, and manganese), Indonesia (nickel and cobalt), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (cobalt), and South Africa (manganese).

Developing countries in Africa and Latin America hold much of the untapped potential, but geopolitical risks, environmental concerns, and processing bottlenecks (often in China) pose challenges.

India, with its ambitious renewable energy target of 500 GW by 2030 and an electric vehicle (EV) boom, sits at the centre of this transformation. Yet the paradox is stark. The country remains fully import-dependent on at least ten of the 30 critical minerals identified by the Ministry of Mines. Over 60 per cent of global refining lies in China’s hands, turning supply chains into geopolitical tripwires. The 2023 lithium price crash and Beijing’s 2025 graphite export curbs were not market accidents; those were warnings about the fragility of India’s green ambitions.

In response, India launched the National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM) in January 2025, with an allocation of Rs 34,300 crore over a seven-year period. This marks a shift from fossil-fuel dependence to mineral self-reliance, with environmental safeguards integrated. Policymakers believe that this is only the beginning, given the evolution of India’s mining sector from colonial-era regulation to modern reform.

Production Paralysis

India’s critical minerals story begins underground, where promise meets paralysis. The country holds 163.9 million tonnes of copper and 44.9 million tonnes of bauxite, yet extraction lags far behind. In July 2025, mineral output increased by 18.3 per cent year-on-year; however, production of key non-metallic minerals declined by 30 per cent. For strategic inputs such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earths, domestic production remains negligible.

Since 2023, five auction tranches have released 38 blocks across 13 States, covering lithium, nickel, and REEs. The sixth round, announced in September 2025, adds more blocks. Even Coal India Ltd, the coal giant, is diversifying into battery metals to leverage its exploration capabilities.

Yet systemic barriers persist. Environmental clearances can take years, and smaller miners often lack the technological know-how to process low-grade ores. The Council on Energy, Environment, and Water notes that since India falls short in domestic refining, it ends up exporting raw ore only to re-import refined metals at premium prices. Recent royalty cuts on graphite from 10 per cent to 4 per cent, and reductions for caesium, rubidium, and zirconium under the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2025, are encouraging. Graphite, crucial for EV anodes, may now see 5-10 per cent annual output growth. But tinkering only with royalties will not suffice.

India needs a ‘Mineral Manhattan Project’ — massive R&D funding for deep-sea mining in its exclusive economic zone, estimated to contain polymetallic nodules worth trillions. Without such boldness, domestic output will remain a trickle in a flood of global demand. The metaphor draws from the original Manhattan Project of the 1940s — a wartime US scientific-industrial mobilisation that brought together USD 2 billion in funding, 1,30,000 personnel, and the world’s top laboratories to achieve a transformative breakthrough in less than four years.

In today’s world, it underscores the scale, speed, and national urgency required to secure critical minerals that increasingly determine geopolitical power, much like nuclear capability did eight decades ago. As global energy systems electrify and China controls 60-90 per cent of processing, India risks strategic dependence unless it mounts a coordinated mission-mode effort.

Leaping Demand

If production is the tortoise, demand is the hare. By 2030, India’s critical minerals market could hit Rs 1.2 lakh crore (USD 15 billion), driven by demand for renewables and EVs. India’s EV fleet may reach 30 million units, consuming lithium at 20 times current import levels. Solar panels will gulp silver and tellurium, and wind turbines will devour copper and neodymium.

The IEA’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 projects that India’s lithium demand will quadruple, and its graphite use will increase 40-fold this decade. Imports have already ballooned to USD 4.93 billion in FY24, a 10-fold rise from FY15. Government production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes have significantly boosted battery and solar manufacturing at Tata’s gigafactory in Gujarat and Reliance’s hydrogen programme. But without sufficient mineral feedstock, these projects face the risk of idling.

Meanwhile, China’s dominance distorts market signals. Beijing’s refining monopoly extends from Sichuan’s lithium plants to Inner Mongolia’s rare-earth hubs, implying that a policy tweak in China can cause global prices to spike overnight. The 2024 restrictions on rare-earth elements and the 2025 curbs on graphite demonstrated how Beijing can weaponise supply chains, just as OPEC did with oil.

India can evolve into Asia’s processing hub, blending domestic demand with value addition. Refining imported lithium into cathodes or cobalt into precursors could create five million jobs by 2035. To achieve this, NCMM funds align with demand-side incentives, such as 20 per cent local-content requirements in EV batteries by 2027.

Trade Imbalance

Trade data lay bare the imbalance in critical mineral transactions. In 2020-21, critical mineral exports reached USD 5 billion, driven by bauxite and ilmenite. By 2023-24, they slipped to USD 3.99 billion due to ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) pressure and pandemic disruptions. Imports surged sharply after 2021-22, widening the trade deficit.

Lithium comes from Australia and Chile, cobalt from the DRC via China, and graphite from Mozambique. This dependence is both economic and strategic. The US has accelerated its push to secure and diversify critical mineral supply chains under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Defence Production Act (DPA), and the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP).

A significant recent development is the emerging US-Pakistan cooperation on critical minerals, particularly Pakistan’s lithium, copper, and rare earths reserves in Chagai and Gilgit-Baltistan etc. If this cooperation progresses, it could reshape South Asia’s mineral geopolitics, offering Washington a foothold in a region traditionally influenced by China, while giving Pakistan an alternative to Chinese Belt and Road financing.

When China restricts exports, prices surge and supply chains strain. New Delhi is quietly hedging. The US-India iCET pact aims at joint stockpiling, while the Green Critical Minerals Agreement with Australia enhances supply diversification within the QUAD. The MoU with Saudi Arabia on Arabian Sea exploration and the UAE’s USD 10 billion lithium-processing investment further strengthen India’s friend-shoring strategies.

But China’s shadow looms large. It also dominates refining, component manufacturing, and recycling, giving it a near-total leverage over global clean-energy value chains. Unless India builds a parallel ecosystem, the country risks being price-takers in technologies central to its energy independence.

Exporting value-added products, such as refined nickel to Europe and processed graphite to Japan, while aligning with EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) traceability norms, could help India reach USD 10 billion in exports by 2030.

Policy Perspective

The NCMM outlines a seven-year roadmap for exploration, processing, recycling, and research and development. It allocates Rs 10,000 crore for auctions and technology transfer, aiming to secure 50 new blocks by 2027. The MMDR Act, 2025, introduces a single-window clearance system, cutting approval times from 18 to 6 months. Coupled with lower royalties, India now offers one of the world’s most pro-miner policy frameworks.

Yet gaps persist. Private participation is weak; junior miners hesitate without state guarantees. Environmental regulations, while necessary, often delay projects in nickel-rich belts. Only 10 per cent of India’s landmass has been systematically mapped, leaving vast geological potential untapped. Recycling remains underdeveloped. Urban mining from e-waste could supply up to 20 per cent of India’s copper and 10 per cent of its lithium needs, but the lack of policy focus and infrastructure continues to be a major challenge.

(Dr Jadhav Chakradhar is Assistant Professor of Economics, Centre for Economic and Social Studies [CESS], Hyderabad. Dr Mini Thomas P is Associate Professor, Department of Economics and Finance, Birla Institute of Technology & Science [BITS] Pilani, Hyderabad Campus)

Related News

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

5 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

5 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

5 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

6 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

6 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

6 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

6 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

6 hours ago