Opinion: Budget 2025-26: Step towards capitalistic state

Focus on ‘rolling back regulation significantly’ by ‘getting out of the way’ is the second version of deregulation

By Nayakara Veeresha

The Union Budget 2025-26 was popularised as the foundation for ‘Viksit Bharat-2047’ through more savings in the hands of the people thereby pushing the demand to usher in growth of the economy. Most of the entrepreneurs, industrialists and corporate entities hailed the Budget as a growth catalyst.

Also Read

Agriculture, micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), investment and exports are the four engines identified for economic growth. No doubt these are important for a growing economy like ours. However, the big missing link is the direction of the Budget and its heavy reliance on deregulation. To push regulatory reforms, the Budget identified four measures: the constitution of a High-Level Committee for regulatory reforms, the Investment Friendliness Index for the States, the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) and Jan Vishwas Bill 2.0. The reason for the deregulation is that India is on the verge of regaining the growth momentum and its sustenance in the context of global economic slowdown and post-Covid.

Agriculture

Against this backdrop, it is essential to understand and analyse the deviation of the Budget from the welfare state and its progression towards the capitalist state under the prism of deregulation. Agriculture remains one of the key sectors for maintaining the growth momentum in spite of its declining contribution to the overall GDP.

Henceforth, agriculture and its allied sector are being identified as the first engine of growth with the allocation of Rs 1,27,290.16 crore which is marginally better than the Budget Estimates (Rs 1,22,528.77 crore) and less than the Revised Estimates (Rs 1,31,195.21 crore) of the 2024-25 Budget. This is despite the announcement of schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Dhan-Dhaanya Krishi Yojana for the benefit of 1.7 crore farmers in 100 districts with low productivity. The allocations to the Transfer to Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Fund and PM-Fasal Bima Yojana have been reduced by Rs 3,621.73 crore for each scheme. Similarly, the allocation for PM Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-Kisan) has been stagnated at Rs 63,500 crore.

MSMEs

The next is MSMEs with the major step being the revision of classification criteria. The total allocation to the MSME sector is Rs 23,168.15 crore which is better than the RE of Rs 17,306.70 crore for 2024-25. Under this, the Development of Khadi, Village and Coir Industries saw a more than 50 per cent increase in allocation with Rs 1,532.16 crore. In the RE of 2024-25, the allocation for the same was Rs 1,011.21 crore.

The Scheme for Fund for Regeneration of Traditional Industries (SFURTI) got an allocation of Rs 360 crore from Rs 70 crore in the RE of 2024-25. Overall, the allocations to MSMEs look impressive, however, what really needs to be seen is the sincerity of the government in effective implementation of the same. This is because there is almost a Rs 400 crore difference between the Budget Estimate of 2024-25 and RE of 2024-25 for the MSME. This is uncalled for a sector with 45 per cent of the share in the total exports of the country.

The reign of capital forces including the market over state institutions is a setback to the welfare of the people, especially poorer sections of society

The Union government’s emphasis on deregulation poses a significant challenge for MSMEs with a double-edged sword kind of situation especially in the post-Covid scenario. A robust institutional mechanism with a dynamic governance framework is necessary for reaping the fullest benefits of MSMEs. The decision to set up a National Manufacturing Mission is a welcome step in this direction.

Investments

The fiscal feasibility of the corporate tax reduction and its implications on growth stimulus needs serious attention in the context of investment as a third economic engine. The Economic Survey 2024-25 indicates that private investments are subdued owing to domestic and international political factors and global economic slowdown. It mentions that the slowdown of investments is temporary and offers a ray of hope by taking into account RBI’s assessment of increased investment intentions of Rs 2.45 lakh crore in FY25 as compared with Rs 1.50 lakh crore in FY24.

Exports

The final growth engine is Exports with the announcement of the Export Promotion Mission by the Ministries of Commerce, Finance and MSMEs. This is more particularly intended for handicraft goods, leather sector, marine products and Railway goods.

The increased allocation for the roads by 2.4 per cent, modified UDAN with the addition of 120 destinations and the upgradation of infrastructure for the horticultural produces and the National Food Technology Institute in Bihar are all important areas in terms of facilitating the exports simulative ecosystem and growth.

The four identified areas of growth engines are at the right place and the Budget gives a ray of hope in the difficult economic times both on domestic and international fronts. The post-1989 economic reforms phase is the first version of deregulation through which the capabilities and competitiveness of the Indian economy saw a steep increase at the global level.

Deregulation 2.0

The Union Budget 2025-26 with its focus on ‘rolling back regulation significantly’ by “getting out of the way” is the second version of deregulation. The philosophical approach of the states rolling back from the micromanagement of the economy to embarking on risk-based regulations is indeed the need of the hour. However, the underlying assumptions of ‘free market’ and ‘perfect market competition’ are distantly related to the informal nature of the Indian economy.

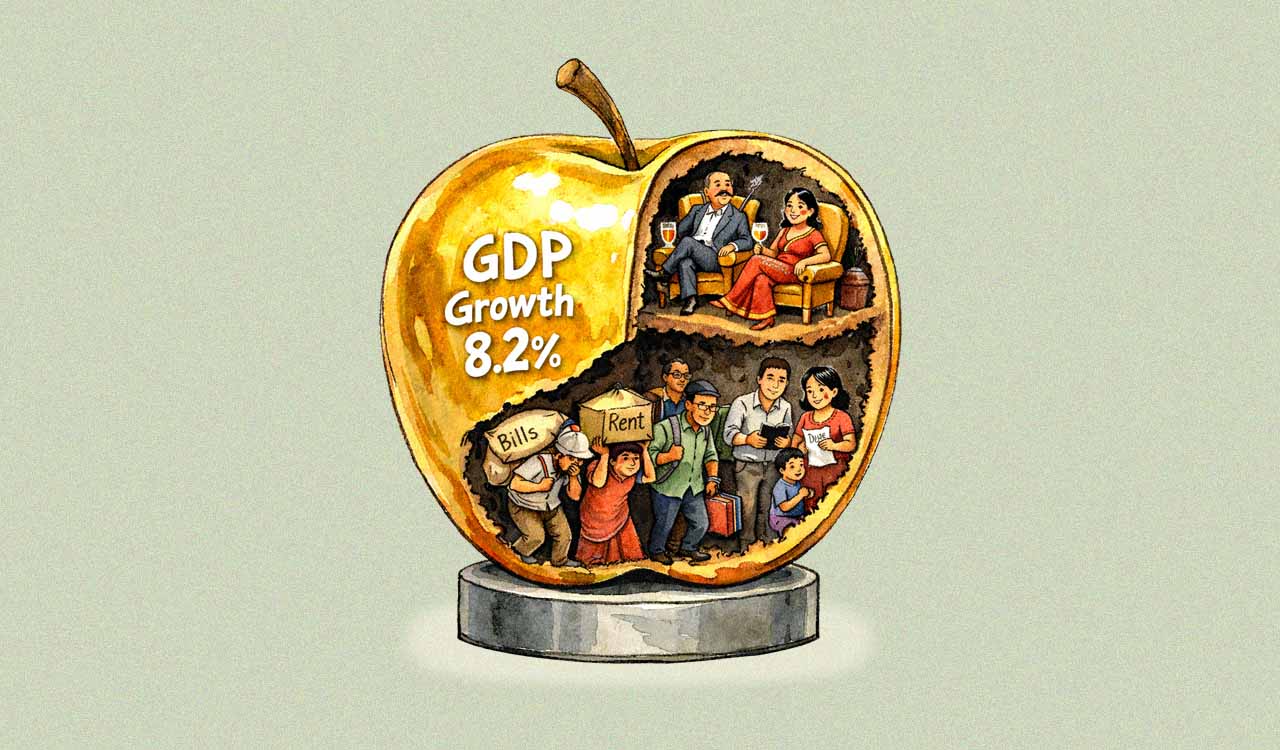

The gradual withdrawal of the state and subsequent rise of the market/private players is one of the central tenets of the capitalist economy. The reign of capital forces, including the market over the state institutions, is a setback to the welfare of the people, especially poorer sections of society.

The Centre missed an opportunity to make use of the Budget as an instrument for further advancing the goals of economic development and social justice, the hallmark of the welfare state. It would have been making better revenue receipts through taxing rich people in the wake of global standard ‘minimum corporate taxation’.

The reduction in the corporate tax has direct ramifications on the social sector expenditure in addition to the failure to boost corporate investment as a growth catalyst. From the foregoing analysis and discussion, it can be inferred that the Budget is more inclined towards the capitalistic state over the welfare state as envisioned in the Constitution.

(The author is Assistant Professor, SVD Siddhartha Law College, Vijayawada. Views are personal)

Related News

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Australia offers refuge to Iranian women footballers amid war

21 mins ago -

Editorial: Nepal rejects the old guard

1 hour ago -

Telangana: Error mars Inter Physics II paper; question goes missing

1 hour ago -

Three-member burglar gang arrested in Hyderabad, stolen property worth Rs 13 lakh recovered

2 hours ago -

ACB catches Kukatpally community organiser taking Rs 18,000 bribe

2 hours ago -

90% of Hyderabad eateries likely to shut down in next 48 hours amid LPG crisis

3 hours ago -

Watch | Flash Strike by Sanitation Workers After CM Revanth Reddy’s Remarks

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Overseas consultancy manager murdered in Madhuranagar office attack

3 hours ago