Opinion: Engines to aid manufacturing

India must capitalise on servitisation and servicification by formulating smart policies

By Aishwarya Harichandan, Dr Sugandha Huria

Shweta purchased a MacBook in 2019. After three years of flawless operation, the MacBook started to show some problems. She visited an Apple Service Centre where they charged her Rs 2,600 to diagnose the issue. Further charges were levied for the repair. At the same time, Apple unveiled a new iPhone model with upgraded features and a better camera. Apple Inc’s R&D made it feasible for this to happen. The branding and marketing strategy for the new version has created a massive craze among the public. The first case demonstrates an example of servitisation, while the second presents the illustration of servicification — a much wider concept.

Gaining Prominence

Servitisation is the process of adding services to a product-focused company to generate additional revenue streams and consistently deliver a desired outcome to clients, frequently to the point where the company becomes predominantly solution-focused. The classic example of this is customer care services, Netflix and Spotify. In the 1980s, the concept of servitisation became popular as a means for manufacturers to set themselves apart from their competitors and develop client connections.

On the other hand, the fragmentation of industrial production into activities such as design, R&D, prototyping services, transportation, marketing, branding, IT services (for example, inbuilt apps in mobile phones), network/communication services and data-processing services is called ‘servicification’ of manufacturing. As an input and an output, the manufacturing sector is thus becoming increasingly reliant on services, which helps boost productivity, efficiency and global competitiveness.

Manufacturing companies are now outsourcing most of these value-chain activities, resulting in increased demand for service providers. Similarly, they are now producing a greater number of services.

There are several reasons that have contributed towards the importance of servitisation and servicification in the current economic order. To begin with, the usage of knowledge-intensive services may aid in the adoption of new technologies; consequently, manufacturing organisations are increasingly relying on services to increase productivity. Second, services such as transportation and communication are becoming increasingly important for manufacturing, necessitating the participation of services in value chains by manufacturing enterprises.

Third, using services (such as maintenance/repair) can be a method for manufacturers to establish customer relationships. Finally, legal services are utilised to help manufacturers overcome market entry restrictions by assisting them in complying with regulations.

India’s Performance

The share of services in the GDP of India has increased from 29.5% in 1950-51 to over 50% in 2021-22. Further, the services export picked up after the 1991 reforms and assumed a major role in cushioning the economy in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. The composition of services export has changed from traditional sub-sectors like transportation towards IT-BPO, which has fuelled the growth of the services sector.

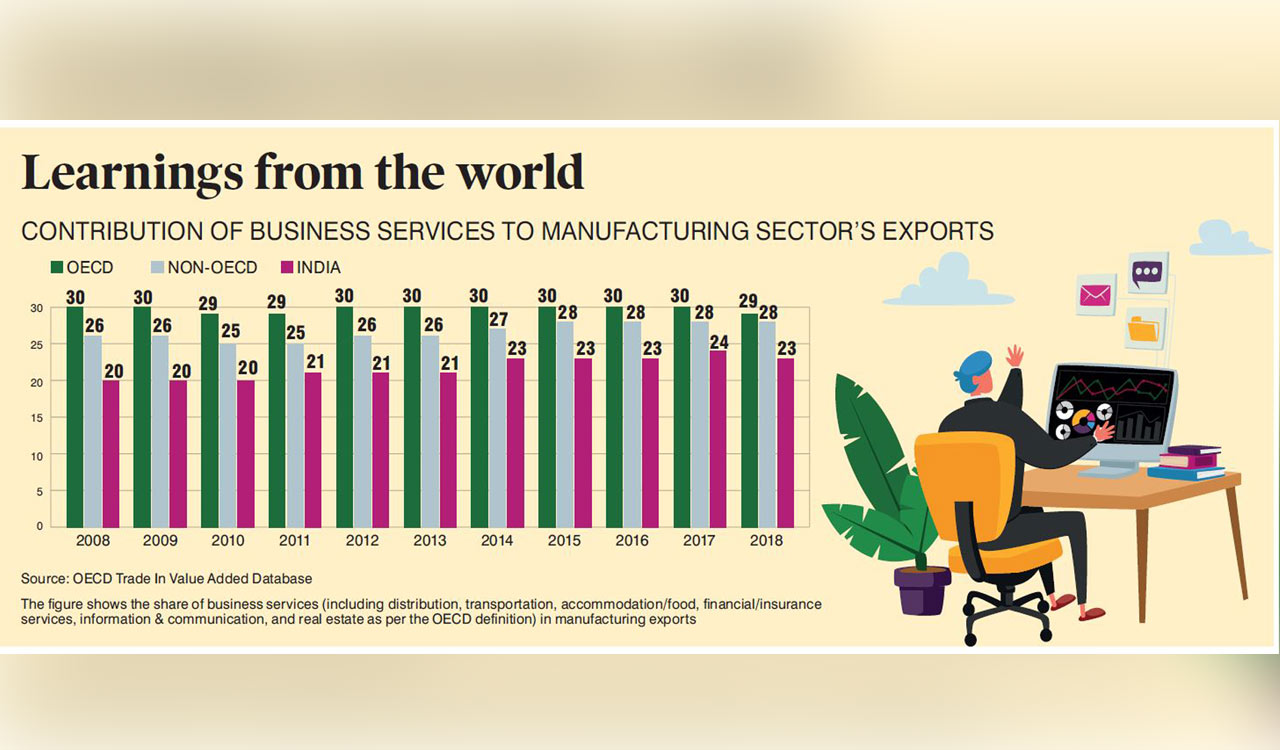

At the same time, the contribution of services to manufacturing exports has increased over the years from 17% in 2000 to 23% by 2018 (see Figure). While OECD countries have business services contributing approximately 30% to manufacturing exports, India’s share has been less than 25%. This provides a major potential for India to tap into the servicification of manufacturing.

There is immense potential for servicification in India. IT and associated services, which account for the majority of India’s services exports, make up a substantially smaller share of gross exports in terms of value-added. This indicates that these services are largely directly exported rather than being embedded in the exports of other segments of the economy, implying a greater opportunity to leverage specific services in the country’s exports from other sectors. The low amount of contribution from R&D and other business operations is particularly remarkable, and it could indicate that Indian manufacturing exports are more likely to be found at the lower end of the value chain, where the possibility for service integration is limited at present.

In 2011, around 90% of all services were of domestic origin (like most developing countries) and much higher than the roughly 60% share of manufacturing value-added contribution to overall exports. Given the sector’s significant contribution to gross exports, the latter would suggest that the competitiveness of domestic services is particularly crucial for overall export competitiveness.

Special Zones

To boost the competitiveness and productivity of manufacturing, host countries are now offering targeted incentives for services utilised in the manufacturing process. Subsidies are being provided to units in special economic zones, high technology zones, etc. These subsidies compensate for logistics, training, marketing and branding costs. For example, subsidies are given to SEZ units in areas like legal, business planning, marketing, skill training, warehousing, security and other support services in Taiwan. Construction facilities are subsidised by the Republic of Korea. The Malaysia Knowledge Park provides benefits such as a double deduction on payments for the utilisation of recognised research institutes’ services.

In 2018, the US had 262 foreign trade zones/logistics hubs, whereas China had 15. Furthermore, the zones are increasingly focusing on offering clients a variety of services. The Kaohsiung SEZ in Taiwan, for example, includes dedicated zones for software and logistics industries, in addition to high-value manufacturing units. China and Russia promote business incubators, and China’s SEZs have a fast-track patenting process. All this has helped augment manufacturing productivity.

India is home to one of the world’s largest number of SEZs. There were 265 active SEZs as of January 2021, with 25 multi-product SEZs and 240 sector-specific SEZs. Sixty per cent of these SEZs are in the IT sector. However, the evidence seems to suggest there exist a lot of untapped potential that these SEZs could leverage to ensure global competitiveness in exports through servicification.

In this situation, the Baba Kalyani Committee’s suggestions serve as a lighthouse. The new SEZ provisions in the Budget 2023-24 have a great deal of potential to capitalise on servitisation and servicification. Additionally, as logistical services make up about 13% of the GDP, they must be adequately subsidised. The PM Gati Shakti Multimodal project is a step in the right direction. Further, subsidising training, electricity, R&D, etc is necessary. Formulating WTO-compliant smart policies like Taiwan, Korea and China, to subsidise the services is required to ensure reaping the full benefits of the servicification process.

(Aishwarya Harichandan is Assistant Professor, Economics and Business Environment, IIM Sirmaur, Himachal Pradesh. Dr Sugandha Huria is Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (Deemed to be University), Delhi)

Related News

-

ACB finds irregularities during surprise check at Dundigal municipal office

9 mins ago -

Congress Ministers flag coordination issues, complain of interference in portfolios at AICC review meeting

23 mins ago -

Gathering evidence on corruption by Telangana ministers, IAS officers, says Bandi

28 mins ago -

MBA graduate dies by suicide in Tellapur

33 mins ago -

Four die by suicide in separate incidents in Medak district

36 mins ago -

Kyathanpalli chairperson stalemate aggravates internal bickering in Congress in Mancherial

42 mins ago -

Mukesh Ambani announces Rs 10 lakh crore AI investment in India

57 mins ago -

AI benefits for Global South and India can be huge: Anthropic CEO

1 hour ago