Opinion: Fast fashion, the runway to climate crisis

Fashion must evolve from being a disposable commodity to a creative practice rooted in responsibility

By Ananya Arora, Avantika Tyagi, Dr Deepa Palathingal

The global fashion industry, valued at over USD 3 trillion in 2021, and employing over 300 million people across its value chain, thrives on a model of rapid production and disposable consumption known as fast fashion. The Cambridge Dictionary defines fast fashion as “clothes that are made and sold cheaply, so that people can buy new clothes often.” While this system delivers affordability and instant gratification to consumers, its environmental and social costs are staggering.

Also Read

Environmental Toll

Textile waste has increased significantly. Globally, more than 92 million tonnes of textiles are discarded annually (EPA, 2025; Quantis, 2018). Poor quality and short lifespans ensure that the waste keeps piling up. Research suggests that online shopping can have a lower carbon footprint than shopping offline, but the rise of e-commerce has led to a change in consumer behaviour, where easy and quick availability has further fueled overconsumption and fast-fashion culture.

According to United Nations Environment Programme reports, fashion contributes 2-8% to global CO₂ emissions, 20% to water pollution, 5,00,000 tonnes of microplastics, and 1.2 billion tonnes of CO₂, which exceeds international aviation and shipping combined. Its water abuse is staggering: dyeing textiles is the second most industrial water polluter, while a single pair of denim jeans requires 10,000 litres of water, the amount an average person would drink in 10 years. The waste water crisis escalates as 73 per cent of garments end up in landfills, while less than 1 per cent achieve textile-to-textile recycling.

Yet the burden is not shared equally. While consumers in wealthier nations enjoy fast, disposable fashion, developing countries bear the brunt of its environmental fallout. Most fabric production and garment manufacturing — and the water use, pollution, and industrial waste — are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries. Even after disposal, rich nations often export post-consumer waste to poorer ones. In Ghana, for example, about 15 million second-hand garments arrive each week, nearly 40 per cent of which are unsellable, overwhelming local markets and landfills.

Overproduction, Overconsumption

The fast fashion industry, valued at USD 150.82 billion in 2024, is projected to reach USD 291.1 billion by 2032, reflecting a CAGR of 10.7 per cent. The business model that thrives on feeding consumer impulses, flooding markets with cheap garments that mirror fleeting trends, rests on two pillars: overproduction and overconsumption. Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram popularise micro-trends overnight, and fast-fashion companies respond rapidly. Leveraging hyper-agile supply chains and rapid design processes, they flood markets with new collections. Chinese online giant Shein, for instance, releases over 10,000 designs daily, exploiting “drop culture” to manufacture scarcity and urgency. “Drop culture” is a modern marketing tactic where products are released only in limited numbers or for a short time, often without prior promotion, with the aim of boosting their appeal and consumer demand.

As overconsumption accelerates, the industry urgently needs systemic reform, stronger policies and a cultural shift toward sustainability and responsibility

Cheap garments are discarded after just seven wears, while three out of five clothes produced end up in landfills every year. Without change, fashion will consume 25 per cent of Earth’s carbon budget by 2050. Synthetic fabrics worsen the crisis, shedding 9 per cent of all ocean microplastics, equivalent to 50 billion plastic bottles annually. The supply chain is complex and difficult to track for emissions. Globally, “65 per cent of the clothing that we wear is polymer-based,” says Lynn Wilson, an expert on the circular economy. Producing polyester fibres requires 70 million barrels of oil annually. Though recycled polyester fabric can help in decreasing carbon emissions as it releases half to a quarter of the emissions of virgin polyester, it cannot be a long-term solution, as polyester releases microfibers with every wash and takes centuries to decompose.

Behind these numbers lies a model built on overproduction, but the Earth and its people can no longer afford the tab. In the last 20 years, global clothing production doubled from 54 million tonnes in 2000 to 116 million tonnes in 2022, with per-capita purchases surging 60 per cent, a trend fueled by ultrafast retailers. By 2030, apparel consumption will hit 102 million tonnes (a 63 per cent rise), while disposal rates outpace use.

The State of Fashion 2025 report highlights that the fashion industry continues to grapple with challenges that keep the fast-fashion cycle spinning. Supply chains remain fragmented, and many designers remain only dimly aware of the environmental toll of their choices. Consumer trends shift faster than ever, driving overconsumption and, inevitably, overproduction. Efficiency improvements by manufacturers offer little relief when demand keeps rising. Meanwhile, copied designs flood markets at rock-bottom prices, squeezing out small designers and stifling genuine innovation.

Pathways for Change

Tackling the environmental and social costs of fast fashion demands both systemic reform and a cultural shift. Technological fixes, though imperfect, can play a role. While large-scale textile recycling remains prohibitively costly, upcycling “deadstock” fabrics and extending the lifespan of garments even by three months can cut environmental footprints by 5-10 per cent (WRAP, 2012).

Equally important is a cultural transformation. Fast fashion thrives on consumer impulses, but changing attitudes toward durability, repair, and reuse can weaken its hold. The rising popularity of vintage clothing, swapping, and mending illustrates the potential of cultural revaluation. Fashion must evolve from being a disposable commodity to a creative practice rooted in responsibility. Small designers, if supported by copyright protections and stronger intellectual property laws, can innovate sustainably while resisting the homogenisation of mass-produced trends.

Beyond regulation, better decision-making tools can amplify impact. Combining Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which measures a product’s environmental footprint throughout its life cycle, with Stakeholder Analysis (SA), which highlights social concerns, can improve Corporate Social Responsibility and accountability across supply chains. These tools help measure the true cost of clothing, not just its price tag. Companies like Levi Strauss & Co. have begun setting ambitious targets, such as cutting supply chain greenhouse gas emissions by 40 per cent across its supply chain by 2025 and reducing emissions in its own operated facilities by 90 per cent.

Policy interventions are essential. California’s Responsible Textile Recovery Act (2004) mandates extended producer responsibility, while France has taxed ultra-fast fashion brands, with fees of up to euro 10 per item by 2030, and banned the destruction of unsold clothing. Revenues will be directed toward supporting sustainable local fashion. These measures offer models for countries like India, where integrating producer responsibility with incentives for sustainable local fashion could be transformative. At the global level, partnerships such as the UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion and initiatives like the World Bank’s ‘X-Ray Fashion VR’ help align industry with climate goals.

The fashion industry stands at a crossroads: continue on its current trajectory of overproduction and waste, or embrace a model that values creativity without compromising planetary health. The pathway forward requires collective will —businesses must adopt transparency, policymakers must enforce accountability, and consumers make mindful choices. Fast fashion has long been celebrated as affordable and accessible, but its hidden costs — soaring carbon emissions, water abuse, and textile waste — are too great to ignore. If fashion is to remain a force of expression, it must shed its wasteful skin and stitch together a future rooted in sustainability. Only then can the runway lead not to climate crises, but toward resilience and renewal.

(Ananya Arora and Avantika Tyagi are student, School of Science, and Dr Deepa Palathingal is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Delhi NCR Campus)

Related News

-

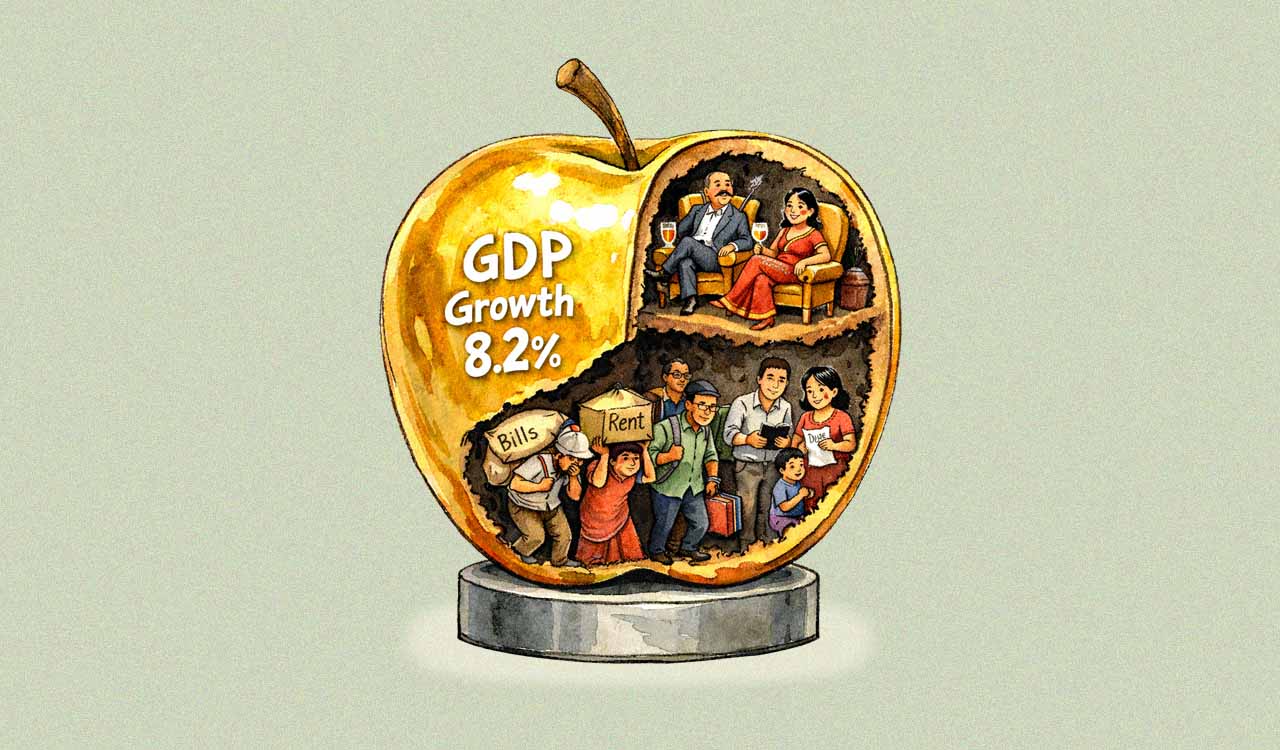

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

1 hour ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

1 hour ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

1 hour ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

2 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

2 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

2 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

2 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

2 hours ago