Opinion: From insurgency to ballots—a new democratic path for India’s Maoists

With mass surrenders and declining relevance of violence, Maoists face a historic opportunity to enter democratic politics

By PV Ramana

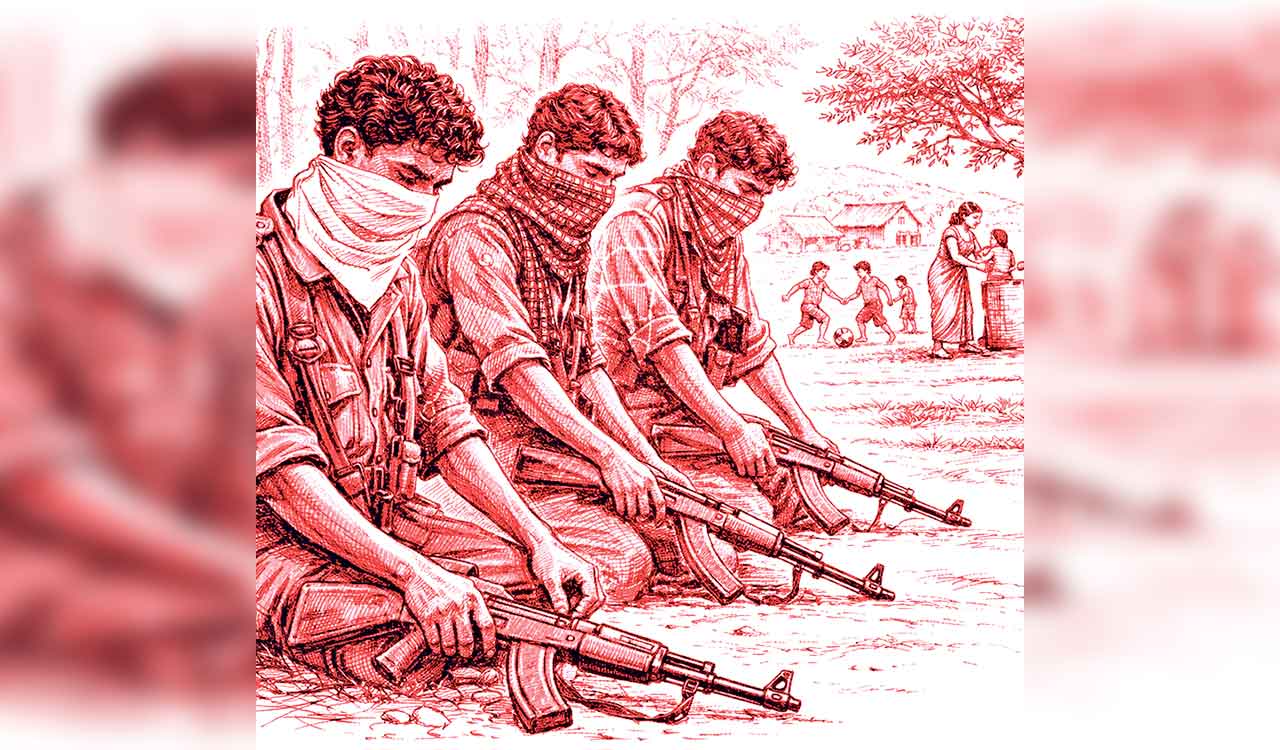

Four Central Committee members of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), or Maoists in short, surrendered in 2025. At least 11 State Committee members, 22 District/Division Committee members, squad commanders and several armed cadre surrendered along with them, together numbering over 450. Official figures of surrenders are much higher, close to 2,000.

A significant number of those who surrendered are not armed cadres but qualify to be termed militants—members of Maoist mass organisations and a few sympathisers. It is estimated that the Maoists have a significantly large sympathiser base of around two lakh.

Political Agenda

Maoist leaders who surrendered have made it clear that they would work among the people. They have admitted that they have not been able to withstand the armed might of the Indian state. Armed revolutionary politics has become irrelevant and expensive—much blood has been shed on both sides.

A possible option for the Maoists now is joining the democratic political stream. They could, and would likely, form a political party. Surrendered high-ranking leaders have given some indication to this effect. Its name and contours are their prerogative; most important is their agenda. The Maoists have several decades of experience in organising the masses. They are a cadre-based organisation with a well-defined hierarchy.

By embracing democratic politics and learning from global Left movements, Maoists could contribute to a more equitable and prosperous India

Ideological commitment to democracy, dedication to serving the people, leading an ethical and disciplined life, and facing the rigours and tumults of political life are quintessential to any political formation.

Transformation

As Mao Tse-Tung said, ‘People to a party are like water is to fish’. The appeal and agenda have to be vast. The Maoists are adept at working among the people; that was how they formed various cadre-based organisations in all their ‘struggle areas’. However, all their mass organisations are underground and have been proscribed by the government. These exist among students, youth, women, the industrial working class, and rural and Adivasi peasants.

The challenge now is to transform them into over-ground democratic organisations. They can, thus, form a strong cadre-based party and may attract more supporters and followers. They need to understand the aspirations of all sections of society. The process is arduous and time-consuming, but possible.

They must come into the open and explain their agenda to the people. First, they have to explain how their armed revolutionary agenda has lost traction. They must be honest and accept their mistakes—for causing much bloodshed—even as they highlight the sacrifices made by many leaders and cadres who left the comforts of life for a rigorous underground life, never to return home. Some of them were brilliant minds—university and college toppers.

In neighbouring Sri Lanka, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, which once spearheaded a bloody insurrection, is now part of the ruling establishment through the National People’s Power (NPP) alliance. In Nepal, the Maoists waged bloody clashes with the police and army, and later stormed to power after abrogating the monarchy. In both cases, they came to power through participatory, competitive and democratic processes. It is hoped that India’s Maoists will be equally wise.

Magic Weapons

First, Maoist leaders should set aside ideological and personality differences. They should build their ‘three magic weapons’—a ‘strong party’, a ‘strong army’ and a ‘strong united front’—in a different way. The ‘strong party’ would be their over-ground democratic political party. They would no longer need a ‘strong army’; instead, they would rely on their propaganda machinery and foot soldiers. Propaganda would be their ammunition and armour.

A ‘strong united front’ could take different forms and is somewhat tricky, as it requires introspection and clear red lines. Once there is a change in ideological mindset, all else will likely fall into place. Initially, they could engage with Left parties with whom they share ideological affinity.

Within the country, the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation [CPI (ML) Liberation]—a naxalite party that traces its origins to the Naxalbari movement and its founder Charu Mazumdar—is a good example of transformation into a party that participates in the democratic process and contests elections. It currently has two members in the Lok Sabha, one in the Bihar Legislative Assembly, and two in Jharkhand.

United Front

Thereafter, they could reach out to other Left parties and become part of a broader Left United Front. Along the way, they could form, support and align with social organisations that need not be political. This would be classic ‘United Font’ tactics. While some hardcore dissenters may still want to remain underground, it would be better for the overwhelming majority to come out of the underground and participate in democratic politics. They could prepare for the 2029 general elections.

They could win a few seats where they command support—especially in Bastar, western Maharashtra and north Telangana—and possibly in parts of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and southern Odisha. By winning a modest number of seats, independently or as part of a Left United Front, the Maoists could contribute to parliamentary politics and bring about incremental change.

Ownership

The government has initiated various welfare programmes, which the Maoists could supplement. To begin with, they could start low-cost education initiatives focused on literacy and skill development. Those who have surrendered need vocational training to be gainfully employed, as do many people in semi-urban, rural and forest areas. Anything begins small. The key is ownership. This would build trust, stakes and an enduring relationship.

Locating trainers is not difficult; some may even be found among the Maoists themselves. Training could be imparted in carpentry, eco-friendly bamboo housing and kitchenware, handicrafts, and packaging of local produce. The next step would be identifying markets which small outlet could address. The infrastructure and finances required are minimal. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the government could provide financial and material assistance, including land use.

The Maoists should welcome government initiatives and support them. Once the mindset changes, everything can change as well. Ideologically transformed Maoists should stop branding such initiatives as anti-class. Later, they could seek assistance from local polytechnics to impart technical skills. They should contribute to the larger project of an equitable, developed and prosperous India, well before the 100th anniversary of our Independence.

(The author, a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, keenly follows the Maoist movement in India)

Related News

-

Women’s T20 WC final schedule announced: India to begin campaign against Pakistan on Jun 14

5 mins ago -

Four senior Maoist leaders surrender in Telangana, State Committee Defunct

17 mins ago -

Ram Charan calls Rathnavelu’s vision ‘magic’ on Peddi sets

31 mins ago -

Hidden genetic risks: Why family history is vital for safe anesthesia

36 mins ago -

Bombay HC: Not every breach of RBI fraud rules warrants court review in Anil Ambani case

47 mins ago -

Sivakarthikeyan announces another film with Seyon director Sivakumar Murugesan

51 mins ago -

Namaz vs Hanuman Chalisa: Lucknow University campus on edge, ABVP workers detained

1 hour ago -

Bad weather forces Hyderabad-bound British Airways flight to land in Nagpur

1 hour ago