Opinion: India–EU FTA, an enabling framework, not an endpoint

The free trade agreement reflects not only bilateral economic logic but also a systemic response to global uncertainty

Dr Mallikarjuna Naik Vadithe

After nearly 18 years of intermittent negotiations, India and the European Union have concluded a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA), marking India’s most economically significant and regulatorily deep trade pact to date. In terms of combined GDP, market size, and rule-making influence, the EU represents the largest economic bloc. The agreement must, therefore, be analysed not as a routine tariff-liberalisation exercise but as a structural repositioning of India within a rapidly fragmenting global trade order.

Also Read

The original India–EU Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA), launched in 2007, stalled after 2013 due to disagreements over tariffs, intellectual property protection, data localisation, public procurement, and regulatory standards. The relaunch of negotiations in 2022 coincided with a fundamentally altered global trade environment characterised by post-pandemic supply-chain disruptions, geopolitical realignments, heightened protectionism in advanced economies, and the strategic recalibration of firms under China-plus-one strategies. In this context, the India–EU FTA reflects not only bilateral economic logic but also systemic responses to global uncertainty.

Trade Trends

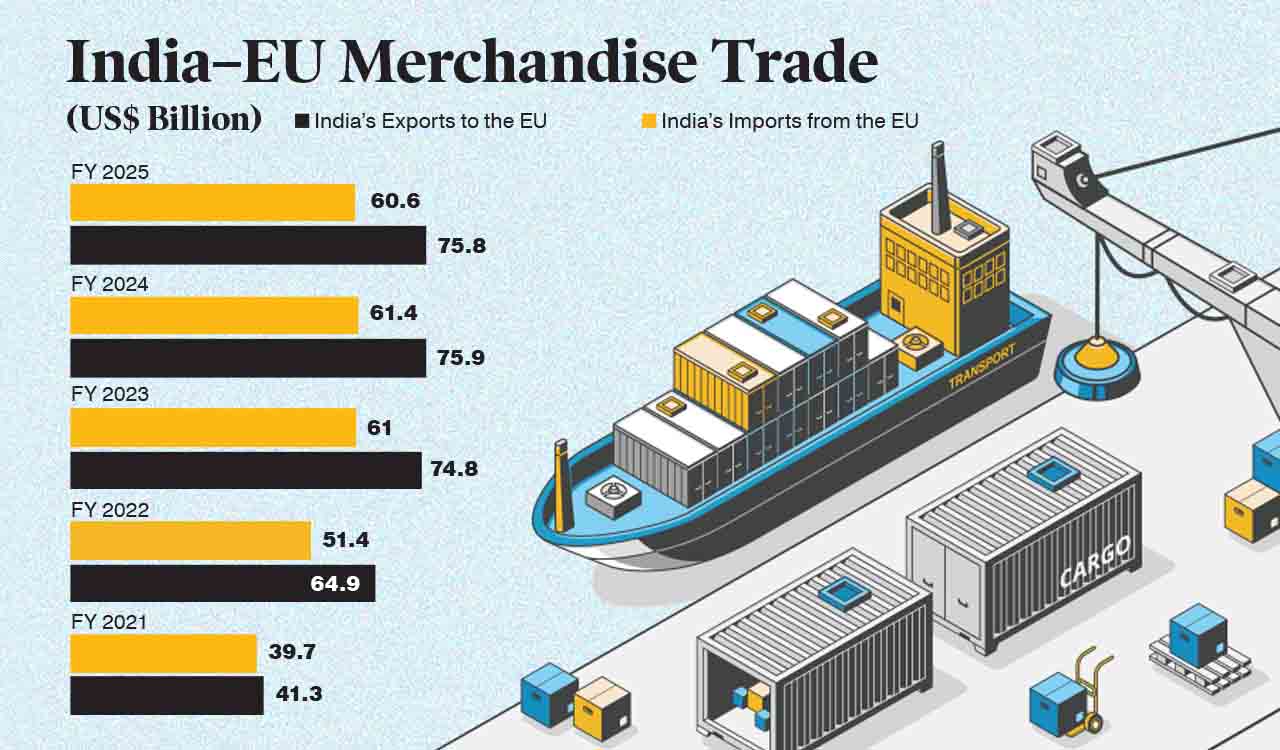

Between FY21 and FY25, India’s exports to the EU expanded by more than 83 per cent, while imports increased at a relatively moderate pace. The resulting pattern indicates that India has maintained a broadly balanced trade relationship with the EU, countering concerns that a deep FTA with a developed bloc would inevitably worsen India’s trade deficit. From a microeconomic standpoint, the observed export growth under MFN conditions suggests the presence of strong demand-side fundamentals and competitive niches for Indian products in the EU market. The FTA, therefore, functions primarily as a friction-reducing mechanism that can amplify existing trade flows rather than generate artificial trade diversion.

Sectoral Composition

India’s export basket to the EU is diversified but remains anchored in labour-intensive, resource-based, and intermediate manufacturing sectors. These sectors are of particular importance from a development and employment perspective.

Labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, apparel, handicrafts, leather goods, and gems and jewellery occupy a central position in exports. These sectors are particularly sensitive to tariff margins, as EU import duties on textiles and apparel typically range from 8 per cent to 12 per cent. Competing exporters such as Bangladesh and Vietnam already enjoy preferential access to the EU market, placing Indian producers at a relative disadvantage.

The agreement’s success will depend on domestic preparedness, MSME compliance capacity, and India’s ability to translate market access into sustained competitiveness and inclusive growth

The FTA corrects this asymmetry by restoring tariff parity and improving price competitiveness. From a socio-economic perspective, this has implications beyond export earnings, as these sectors employ large numbers of low- and semi-skilled workers, many of whom are concentrated in MSME clusters. Government estimates indicate that tariff liberalisation and regulatory facilitation under the agreement could unlock the export potential of approximately Rs 6.4 lakh crore over the medium term, implying significant employment and income multipliers.

Imports, Tech Transfer

India’s imports from the EU are mainly capital- and technology-intensive goods, unlike its exports. This difference matters because these imports are mostly intermediate and capital goods, not final consumer products. Aircraft components, industrial machinery, medical equipment, and advanced telecom instruments serve as inputs into domestic manufacturing, infrastructure, healthcare, and digital connectivity.

Consequently, the FTA’s import effects are likely to be productivity-enhancing rather than consumption-distorting. From a research perspective, this pattern suggests that the FTA may facilitate the diffusion of technology and industrial upgrading. By lowering the cost of high-quality capital goods, the agreement supports India’s long-term competitiveness and complements its domestic industrial policies, such as the Production-Linked Incentive schemes.

Non-Tariff Dimensions

A defining feature of the pact is its regulatory depth. The agreement spans goods, services, trade rules, investment protection, and sustainability standards across approximately 20 chapters. Unlike tariff-focused FTAs, this agreement embeds trade within a broader regulatory and framework. Non-tariff measures are the main challenge for Indian exporters. EU regulations such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, deforestation-free supply-chain requirements, chemical standards under REACH, and traceability norms for textiles and electric-vehicle batteries raise compliance costs and operate as de facto trade barriers, particularly for MSMEs.

The agreement does not eliminate these regulatory instruments but institutionalises mechanisms for dialogue, transparency, and phased adjustment. Simultaneously, the EU has raised concerns over India’s quality control orders and localisation policies. The FTA thus reflects a negotiated equilibrium in which regulatory differences are managed through structured engagement rather than unilateral enforcement.

Services Trade, Data Governance, and Skilled Mobility

Services trade represents one of India’s strongest comparative advantages and constitutes a strategically important component of the agreement. India has sought recognition as a data-secure country under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation framework, a move that would significantly ease digital services exports.

Provisions governing the temporary movement of skilled professionals are expected to benefit information technology, consulting, financial services, and healthcare. This marks a shift from a goods-centric trade agreement to a hybrid model that includes digital trade, data governance, and human capital mobility, with potential long-term gains exceeding those from tariff cuts in goods trade.

At the strategic level, the India–EU FTA aligns with the Atmanirbhar Bharat approach, which emphasises integration into global value chains rather than inward-looking autarky. The agreement enhances trade diversification and provides a stable export destination amid rising US tariff uncertainty and global geopolitical tensions. Macroeconomically, improved export earnings, technology-oriented imports, and potential investment inflows are likely to strengthen India’s external sector resilience. However, the realisation of these gains will depend on domestic preparedness, including infrastructure quality, standards compliance capacity, and institutional coordination across ministries and states.

To Sum Up

The agreement represents a structural recalibration of India’s trade policy towards comprehensive, rules-based engagement with a major advanced economic bloc. Empirical trade data indicate substantial upside potential, particularly in labour-intensive manufacturing and services. At the same time, the agreement’s regulatory depth imposes new demands on India’s export ecosystem, particularly on MSMEs.

From a research-informed perspective, the agreement should be viewed not as an endpoint but as an enabling framework. Its developmental outcomes will be determined by the quality of implementation, the momentum of domestic reform, and India’s ability to translate market access into sustained competitiveness and inclusive growth.

(The author is ICSSR-Postdoctoral Fellow, Centre for Economic and Social Studies [CESS])

Related News

-

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

HCA: Visaka Group will spend entire amount of Rs 64 crore on infrastructure in districts, says Vivek

3 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Indian boxers shine on day four at World Boxing Futures Cup

7 hours ago -

Nikki Pradhan achieves another milestone, completes 200 international caps

7 hours ago -

Telangana sets up Rythu Discom, liabilities of Rs 71,964 crore shifted

8 hours ago -

Iran targets ships, Dubai airport in Gulf escalation

8 hours ago -

FIH Qualifiers: India scores big win against Wales, storm into semifinal

8 hours ago -

India allows FDI under automatic route for firms with less than 10 per cent Chinese stake

8 hours ago -

IEA agrees to record emergency oil release to calm global prices

8 hours ago