Opinion: Judiciary and women’s rights

The Supreme Court verdict in Sarita Choudhary Vs HC of Madhya Pradesh & Another is a significant step towards gender equality

By Nayakara Veeresha

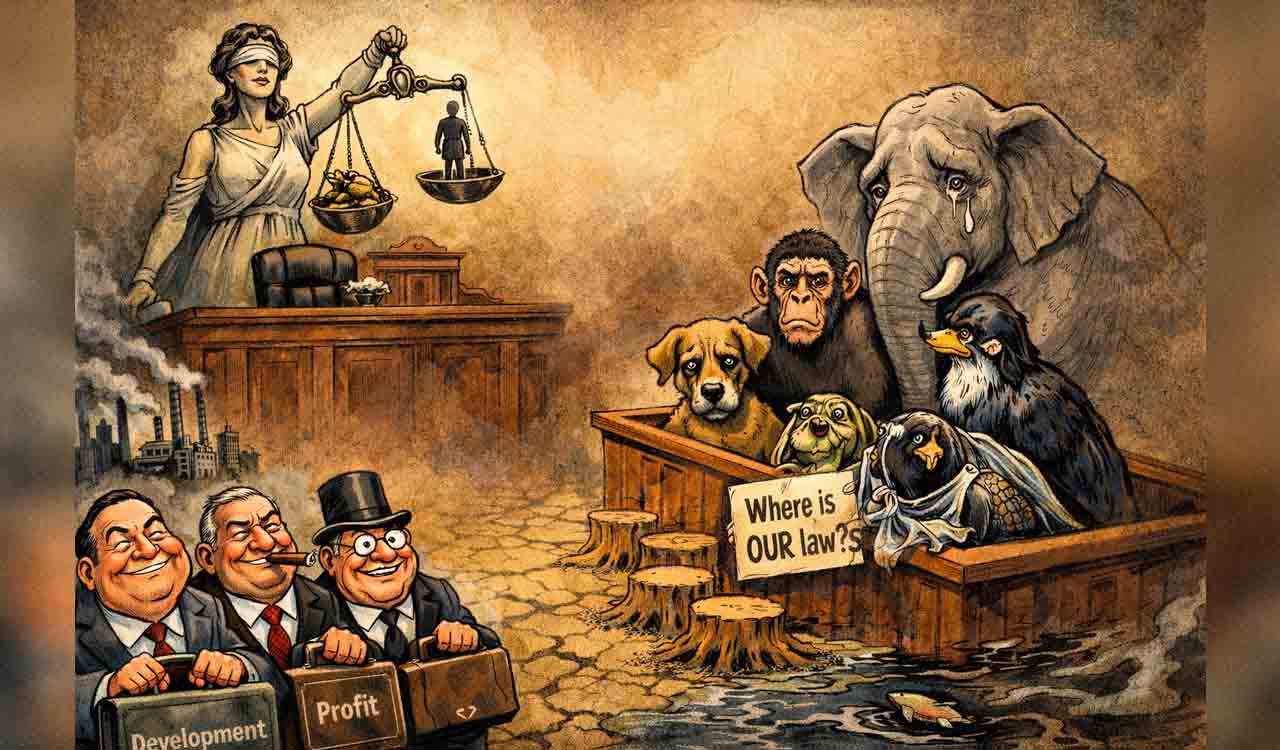

In India, patriarchy poses the biggest challenge to women’s empowerment. Patriarchal mindsets and approaches are widely visible in our society where barriers are more in number than the ones facilitating gender equality. This has hampered the rise of women at home, workforce and in governance. Enabling our homes, workplaces and government with an encouraging ecosystem for women empowerment is essential, along with ensuring a minimum of 50 per cent women representation in the same.

Appreciating Rights

Towards this end, on 28 February 2025, the Supreme Court of India delivered a significant verdict in the case of Sarita Choudhary vs High Court of Madhya Pradesh & Another. This is a suo moto case of higher judiciary and unique in its criticality in the context of the efficiency of women at the workplace and the judiciary in particular. The judgement serves as a reminder of societal unwillingness, in general, to appreciate and recognise women’s rights with specific reference to the transparency of performance assessment of trainee judicial officers based on Annual Confidential Reports (both petitioners), reproductive rights and bodily autonomy (second petitioner only).

The Supreme Court order said enabling a secure and safe work environment for women was more important than increasing their number at the workplace. In this case, the challenge was against the order of termination of six women judicial officers based on recommendations of the Administrative Committee of the High Court of Madhya Pradesh in May 2023. The committee found that based on ACRs, assessment chart, consistently poor performance/work done and other materials, the decision was made to terminate the six probationers.

Taking this into cognisance, then Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud registered a suo moto case in November 2023 and requested the Full Bench of the High Court of Madhya Pradesh to reconsider their termination, of which four had filed writ petitions before the Supreme Court.

Subsequently, four women judicial officers were reinstated in August 2024. Now, the highest court reinstated the other two women judicial officers, namely Sarita Choudhary and Aditi Kumar Sharma. The Supreme Court, in the latter’s case, observed that the “termination of this officer is not termination simpliciter but appears to be stigmatic” despite finding that the “judicial work of the petitioner appears to be excellent” by the Principal District and Sessions Judge.

Principles of Natural Justice

Both the petitioners were not provided an opportunity to represent themselves before the High Court on the observations made in the ACR and on complaints received against them. Hence, the order found that both the officer’s termination by the High Court was contrary to the principles of natural justice and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution.

The counsel, who appeared on behalf of the High Court, stated that the termination was based on a “comprehensive view formed on a holistic and overall performance of the judicial officers rather than any specific misconduct”. It mentioned that the service rules do not contemplate any prior notice or opportunity of hearing before the discharge or termination of a probationer, and hence the termination was not punitive. It is submitted that one of the petitioners, Sarita Choudhary, was given warnings repeatedly on complaints ranging from “misbehaviour, indiscipline, administrative and work-related issues”.

The judgement will become a reference document for future generations to reflect upon how the law intersects with institutional injustices that are rooted in patriarchy

The top court found that the ACR for 2022 was positive with integrity, good personal relationships and high disposal in the case of the former petitioner. In the latter’s case, the “judicial work, quantity and quality wise is very good with her administrative work”, even as it recognised the fact of inadequate disposal of the cases during the pandemic period. This was more owing to the health issues, especially after suffering from a miscarriage.

The Supreme Court observed that the ACRs were adverse in nature, materials placed in support of poor performance did not support the argument for inconsistency in work, and the complaints were neither concluded nor pending against the officers. Hence, it disapproved of the complaints of misconduct and “inefficiency” and found them as stigmatic in nature against the terminated probationers. It noted that the “High Court has erred in acting agnostic to, inter alia, claims of insubordination of petitioner — Sarita Chaudhary — and acute medical and emotional conditions battled by petitioner— Aditi Kumar Sharma”.

Gender Equality

The top court has answered positively to the question of “Are courts that roughly follow public opinion capable of performing counter-majoritarian function — protecting minority rights against majoritarian excesses?” raised by Aharon Barak (2002) in Foreword: A Judge on Judging: The Role of a Supreme Court in a Democracy.

It observed, “Female judicial appointments, particularly at senior levels, can shift gender stereotypes, thereby changing attitudes and perceptions as to appropriate roles of men and women”.

A pregnancy miscarriage has deep physical, mental and psychological after-effects on a woman, and the courts need to be cognisant of these aspects to advance the constitutional vision of gender equality. While saying this, the top court did not reduce the importance of judicial performance by the probationers irrespective of gender and backed gender neutrality.

The interplay between the Legislature, Executive and the Judiciary is a complex one. Delineating the nuances behind this complexity is essential to understanding the institutional interaction in a functional democracy. The country’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, once said, we need judges of “the highest integrity who can stand up against the executive government and whoever might come in their way”.

The Supreme Court is one of the critical institutions of our democracy, recognised internationally for its anti-majoritarian stand. In this instance, it proved once again that it could break the shackles of patriarchy through its sharp yet firm, focused and rational judgement. This judgement will become a reference document for future generations to understand and reflect upon how the law intersects with the institutional injustices that are rooted in the patriarchy and other such hegemonic mindsets of the people in a deeply divided society of ours.

(The author is Assistant Professor, SVD Siddhartha Law College, Vijayawada. Views are personal)

Related News

-

Hidden genetic risks: Why family history is vital for safe anesthesia

5 mins ago -

Bombay HC: Not every breach of RBI fraud rules warrants court review in Anil Ambani case

16 mins ago -

Sivakarthikeyan announces another film with Seyon director Sivakumar Murugesan

20 mins ago -

Namaz vs Hanuman Chalisa: Lucknow University campus on edge, ABVP workers detained

30 mins ago -

Bad weather forces Hyderabad-bound British Airways flight to land in Nagpur

43 mins ago -

Karnataka HC restrains police action against Ranveer Singh in deity row

49 mins ago -

Japanese woman’s Marathi learning video triggers debate, Raj Thackeray reacts

55 mins ago -

Bullet-wounded canine soldier ‘Tyson’ recovering well: Indian Army

1 hour ago