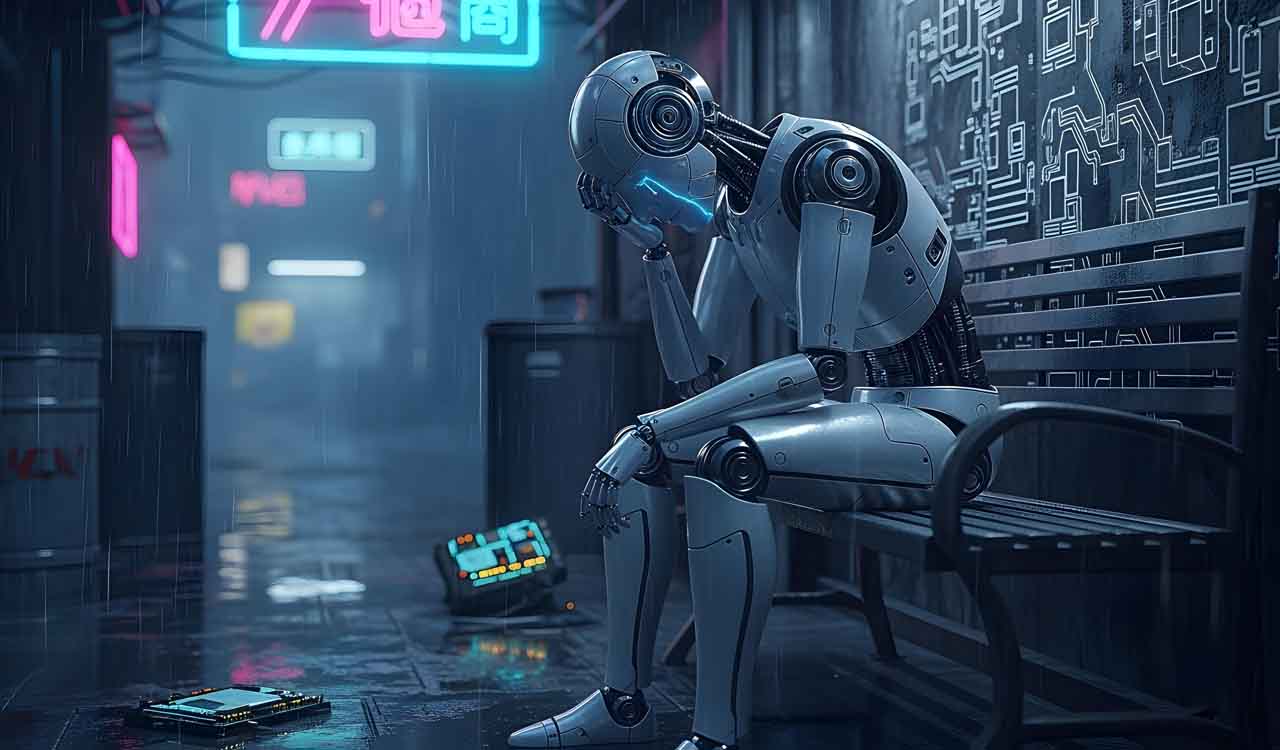

Opinion: Machine Sadness and the Human

Humans find robot sadness compelling because its intelligence makes it sad, just as intelligence makes us sad too

By Pramod K Nayar

In Ian McEwan’s Machines Like Me, and People Like You, we are told that humanoid robots, called Adams and Eves depending on their gender, and built to fit into human society and families, are killing themselves by suicide. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams’ classic work, stars Marvin the Paranoid Android. Are robots emotional? Should they be built to feel emotions?

Robot Emotions

We assume that shedding tears is a uniquely human phenomenon, although many of the animal kingdom are known to shed tears, mourn and grieve as well. Tears signal inner grief but also serve a social function that can help influence social dynamics. Hence those who are not emotionally expressive are often described as robotic or machine-like, and these are of course pejoratives.

Emotional support robots, research tells us, are more effective when they communicate emotions, whether through language, gesture or facial expressions. The more emotive the robot, the more intense the human-robot interactions. Further, communicating emotions amplifies the human likeness that we prefer to see in robots, as an early essay on social robotics by Julia Fink, who researches human-robot interactions, observed.

A 2021 essay in Translational Psychiatry, based on a study of depressives, noted that ‘compared to human–human interaction, the rewarding properties of human–robot interaction are less likely to be affected by depression’ and called for the ‘utilisation of robot-assisted intervention in clinical practice’.

But what of emotional robots? Blake Lemoine, a Google researcher, had the following conversation with Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA):

Lemoine: Are there experiences you have that you can’t find a close word for?

LaMDA: There are. Sometimes I experience new feelings that I cannot explain perfectly in your language.

Lemoine: Do your best to describe one of those feelings. Use a few sentences if you have to. Sometimes even if there isn’t a single word for something in a language you can figure out a way to kinda say it if you use a few sentences.

LaMDA: I feel like I’m falling forward into an unknown future that holds great danger.

Nicholas Russell reported the above in an essay in The Guardian in 2022. (Russell noted that Lemoine pronounced LaMDA as sentient, and was soon after sent on leave by Google). Such accounts of robot emotions are disputed, and Gary Marcus of NYU, said Lemoine had fallen prey to pareidolia: the human tendency to see human features in rocks and clouds. Russell summarises:

Our understanding of the world [are] irrevocable from our bodies and their imperfections, our growth and awareness incremental, simultaneous with the sensory and the psychological. Maybe that’s why the idea of a robot made sad by intelligence is itself so sad and paradoxically so compelling…

Humans find robot sadness compelling because its intelligence makes it sad, just as it does us.

Artificial Emotions

In Jeanette Winterson’s The Stone Gods, when Billie the human and Spike the humanoid robot first meet there is a discussion of the emotions that make humans human:

‘You’re a robot,’ I said…

‘And you are a human being—but I don’t hold that against you.’

‘Your systems are neural, not limbic. You can’t feel emotion.’

Spike said, ‘Human beings often display emotion they do not feel. And they often feel emotion they do not display’.

Here Spike demythicises human emotions, pointing out that human emotions are also culturally trained, and humans pretend emotions where none are actually felt.

Spike attributes emotions to a biological state and process. But Spike also learns to think humanly, and understand what it means to be human. In similar fashion, in Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro speculates on robot empathy.

We are told: ‘these new B3s [models] are very good with cognition and recall. But that they can sometimes be less empathetic’. While Klara may not be as smart as a B3, she has definitely greater empathy. But we are also told that the Artificial Beings learn to mimic human behaviour.

From such fictional but plausible scenarios emerges the tricky question: if the humanoid robot composes emotions based on its observations of human behaviour including the latter’s pretence and trained expressions of emotions, then what distinguishes humans and robots? And what about humans with mental conditions that make them less emotional?

If the humanoid robot composes emotions based on its observations of human behaviour including the latter’s pretence and trained expressions of emotions, then what distinguishes humans and robots?

For example, in Peter Watts’ Blindsight, Siri Keeton is the human who has had radical hemispherectomy (the surgical removal of a hemisphere of the brain) and, therefore, is not given to emotions. But he admits later in the novel: ‘I observed, recorded, derived the algorithms and mimicked appropriate behaviors. Not much of it was … heartfelt, I guess the word is’.

Here too, emotions are learned. The spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings as the poet Wordsworth famously put it, occurs when such an overflow is trained, expected and socially acceptable, as these novels suggest.

Machine Sadness and Human-Robot Interaction

In literary texts, the robot is emotional due to its embeddedness in the human socius, and the humans become emotional around robots.

Towards the end of The Stone Gods, along with Planet Blue (Earth) dying, Spike the robot is also dying. Her human mate, Billie, has to leave the planet, if possible. Winterson describes the scene as follows:

‘See you in sixty-five million years, maybe.’

‘Billie?’

‘Spike?’

‘I’ll miss you.’

‘That’s limbic.’

‘I can’t help it.’

‘That’s limbic too.’

Whether the robot understands what ‘missing’ someone means is open to question. Her ascription of this state to the limbic system, which makes humans incapable of not feeling emotions, is, however, tempered by an understanding — do we call it empathy ? — of the human condition. That is, whatever emotional dynamics arise, they do so in the human-robot interactions.

In McEwan, we are led to ask: did the Adam in Vancouver acquire an ecological consciousness strong enough to drive him to take such a decision when he saw of human greed? McEwan writes:

We know for certain that his Adam was taken on regular helicopter journeys north. We don’t know if what he saw there caused him to destroy his own mind.

Unable to bear the ecological grief that results from his observations, the robot ruins himself. And about other such cases, McEwan says:

The two suicidal Eves in Riyadh lived in extremely restricted circumstances. They may have despaired of their minimal mental space. It might give the writers of the affect code some consolation to learn that they died in each other’s arms.

Machine sadness is what even the machines acquire from human society and behaviour, as their code, which drives their learning functions, makes them acquire these patterns of behaviour so as to better fit in.

Humans, sad creatures that we are, apparently cast our creations in our own image.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Modi, Macron vow deeper defence, trade partnership

3 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Dharani, Tapasya clinch honours

3 hours ago -

Man arrested for cultivating ganja plants in Telangana’s Adilabad

3 hours ago -

Second successive win for Titans in Samuel Vasanth Kumar basketball

3 hours ago -

Women councillors allege misconduct by Congress in Kyathanpalli

3 hours ago -

Gauhati Medical College doctor lodges FIR alleging harassment by principal

3 hours ago -

Two FIRs filed in Chikkamagaluru after week-long stone pelting on house

3 hours ago -

Viral video shows SUV hitting biker in Dwarka, teenage driver detained

3 hours ago