Opinion: No longer on demand — How VB-G RAM G weakens rural India

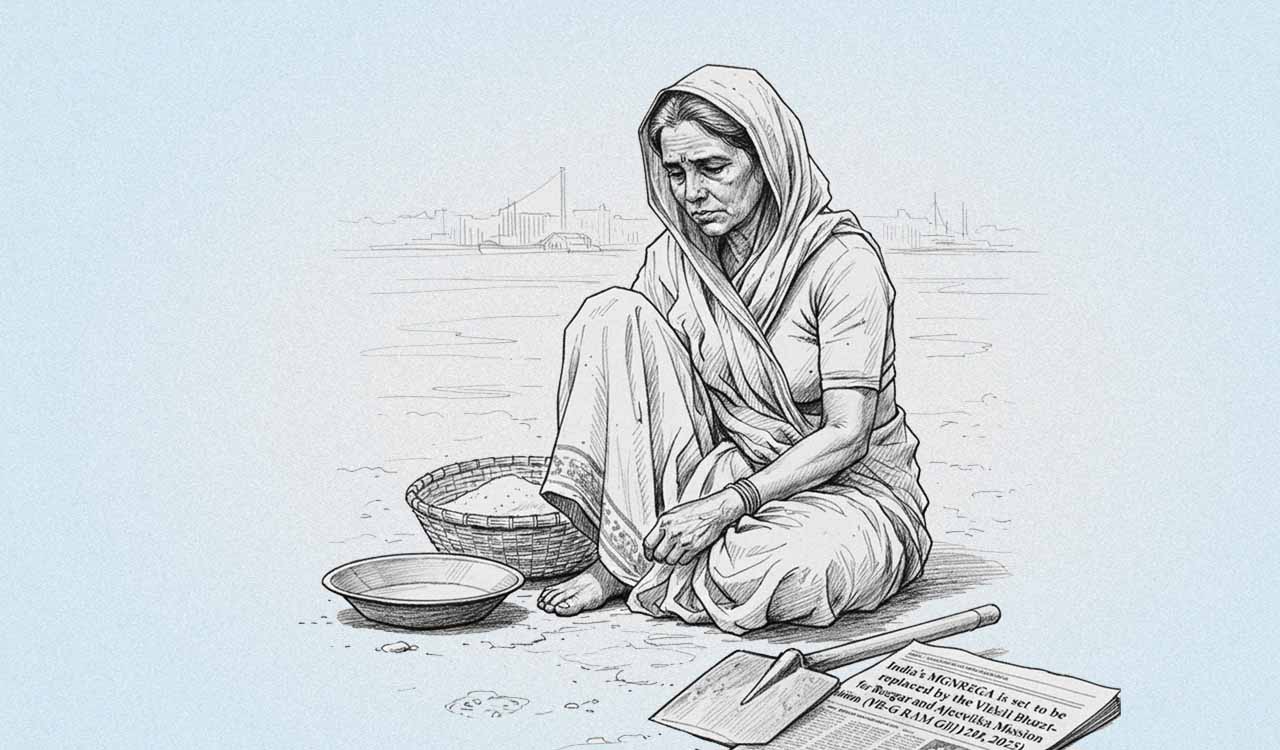

Employment guarantees must remain demand-driven, flexible during crises, and rooted in local decision-making; VB-G RAM G falls short

By Vijay Korra

In the vast rural expanse of India, where more than 60 per cent of the population continues to rely on agriculture and casual labour for survival, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) has, since 2005, stood as a rare rights-based social contract. By guaranteeing 100 days of unskilled wage employment per year to every rural household willing to work, it offered not merely jobs but dignity, security, and a measure of resilience against shocks.

Also Read

MGNREGA’s design was revolutionary. Any adult in a rural household could demand work, and the state was legally bound to provide it within 15 days or pay unemployment allowances. This demand-driven structure ensured flexibility during crises such as droughts, floods, or economic downturns. By mandating that at least 60 per cent of funds go toward wages, it created immediate income security while also building durable community assets — such as ponds, roads, and irrigation systems — that enhanced agricultural productivity.

Evidence of its impact is robust. Studies have shown that MGNREGA reduced poverty among beneficiaries by as much as 26 per cent, boosted household earnings by 14 per cent, and improved school attendance. Over the course of two decades, it generated billions of person-days of work, disproportionately benefiting women (over half of the participants) and Scheduled Castes and Tribes (around 40 per cent). Water conservation structures, for instance, not only provided wages but also improved groundwater levels and reduced soil erosion, strengthening rural economies in the long run.

A Sudden Overhaul

In December 2025, however, the government replaced MGNREGA with Viksit Bharat–Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin), or VB-G RAM G. While promising 125 days of employment and a focus on “transformative” assets, the new framework shifts the scheme from worker empowerment to centralised control. Unlike MGNREGA’s demand-driven ethos, VB-G RAM G introduces a supply-driven model. The Centre now sets State-wise “normative allocations” based on opaque parameters, capping funding upfront and ignoring actual demand.

Under MGNREGA, budgets could expand to meet needs; under VB-G RAM G, workers may simply be turned away once allocations are exhausted. This is not a minor administrative tweak but a fundamental departure from the guarantee principle. During the Covid pandemic, MGNREGA absorbed millions of returning migrants when private jobs vanished. In a capped system, such surges would likely result in rationing, leaving families without income at their most vulnerable moments.

Blackouts and Labour Rights

Equally troubling is the introduction of “blackout periods,” allowing States to suspend the programme for up to 60 days during peak agricultural seasons. Proponents argue this prevents MGNREGA from “cannibalising” farm labour. Yet critics see it as a direct assault on workers’ rights. Rural India is already plagued by disguised unemployment and low farm wages. MGNREGA historically pushed up private sector pay by creating competition for labour, with studies showing wage gains in villages where implementation was strong.

MGNREGA’s imperfections — leakages, uneven asset quality, delayed payments — were real, but they did not negate its role as a floor against destitution

Blackouts could reverse these gains, forcing workers back into exploitative agricultural jobs at below-market rates or into outright idleness. For the landless poor, who form a significant share of beneficiaries, this means denial of employment, exacerbating hunger and debt. In States such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where agricultural seasons overlap with monsoon-induced job scarcity, millions risk being trapped in cycles of deprivation.

Weakening Asset Creation

Asset creation was a cornerstone of MGNREGA’s success. Gram sabhas prioritised works such as afforestation, water harvesting, and rural connectivity, ensuring that projects were locally relevant and sustainable. Several studies found that these assets improved agricultural land, regenerated water resources, and indirectly boosted household health and education. VB-G RAM G shifts focus to “climate-resilient” and “infrastructure-focused” assets aligned with the government’s Viksit Bharat 2047 vision.

While progressive in rhetoric, the top-down allocation risks inefficiency. Centralised notifications of implementation areas mean the Centre can cherry-pick zones, potentially excluding high-poverty pockets not deemed “strategic.” If funding is capped and blackouts enforced, fewer person-days will translate into fewer assets built. This could convert a safety net into a state-led growth tool, prioritising macro goals over micro-level survival.

Fiscal Burdens and Unequal Implementation

The fiscal restructuring further burdens the States. Under MGNREGA, the Centre covered 100 per cent of wages and 75 per cent of material costs, resulting in a 90:10 Centre–State ratio. VB-G RAM G shifts more responsibility to States, especially for materials, despite their already strained budgets. Poorer States such as Odisha or Jharkhand may be forced to cut corners, resulting in delayed payments or subpar assets. Delayed wages have long plagued MGNREGA, but the new caps could worsen this, pushing workers into distress borrowing from moneylenders at usurious rates.

The human cost is profound: families skipping meals, pulling children out of school, or migrating en masse to urban slums, thereby straining already fragile urban infrastructure. Women, who relied on MGNREGA for independent income, face heightened vulnerability to domestic exploitation. In climate-stressed regions such as drought-prone Maharashtra, reduced asset creation means diminished resilience, amplifying deprivation.

Narrative of ‘Modernisation’

Government defenders claim the changes modernise the scheme for a $4-trillion economy, citing declining rural poverty from 25.7 per cent in 2011–12 to 4.86 per cent in 2023–24 and synergies with direct benefit transfers. Yet these claims ignore ground realities. Poverty metrics are contested, and cash transfers cannot replace the dignity of work or the community benefits of locally created assets.

Economists such as Jean Drèze have warned that dismantling MGNREGA is a “historic error,” eroding a global model that cushioned shocks and empowered the voiceless. VB-G RAM G does not evolve MGNREGA; it eviscerates it. By centralising control, imposing caps, and introducing blackouts, it denies employment to those who need it most, hampers meaningful asset creation, and condemns the rural poor to deeper poverty.

Rights-Based Guarantees

India’s aspiration to achieve developed status by 2047 must not come at the cost of sacrificing its most vulnerable citizens on the altar of “efficiency.” MGNREGA’s imperfections — leakages, uneven asset quality, delayed payments — were real, but they did not negate its role as a floor against destitution. In 2023, India’s multidimensional poverty affected 235 million people, with another 269 million considered vulnerable. Weakening the guarantee risks swelling these numbers.

Restoring a true rights-based approach is essential to prevent a humanitarian rollback. Employment guarantees must remain demand-driven, flexible during crises, and rooted in local decision-making. The rural heartland, already beating faintly under economic pressures, cannot afford this wound.

(The author is Associate Professor, Centre for Economic and Social Studies, Hyderabad)

Related News

-

Deadly avalanche kills eight skiers in California

3 hours ago -

Ayodhya priest questions Telangana govt’s Ramzan relief move

4 hours ago -

Titans emerge champions in sixth Samuel Vasanth Kumar memorial basketball tournament

4 hours ago -

Hyd Open golf championship to kick off from February 19

4 hours ago -

Jammu and Kashmir enter Ranji Trophy final with win over Bengal

4 hours ago -

Telangana High Court seeks ground report on forest plantation at Damagundam

4 hours ago -

Sahibzada Farhan century powers Pakistan to big win over Namibia

4 hours ago -

Chief Minister’s Cup 2025 sees record participation across Telangana

4 hours ago