Opinion: PLI welcome but not enough

By B Sambamurthy India has been striving hard to accelerate the growth of the manufacturing sector. There has been no surfeit of initiatives by governments over the last two decades. But the results are suboptimal. The share of manufacturing, which was about 15% of the GDP during 2000, crawled over the next two decades to […]

By B Sambamurthy

India has been striving hard to accelerate the growth of the manufacturing sector. There has been no surfeit of initiatives by governments over the last two decades. But the results are suboptimal. The share of manufacturing, which was about 15% of the GDP during 2000, crawled over the next two decades to just about 18% in 2020. Annual employment generation is a measly 1%. The 25% goal has eluded us.

The Prime Minister gave a clarion call to make India a global manufacturing hub and economic powerhouse. Ease of doing business, plug-and-play infrastructure, opening up new sectors for FDI are among the major projects that have begun to attract investment.

PLI Scheme

In a serious bid to give a major push to manufacturing, the government launched the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme in 2020. The scheme is very innovative in many ways. It envisages, among other things, incentives up to 6% of incremental sales; has a budget outlay of nearly Rs 2 lakh crore for the next 5 years. The Finance Minister said this programme is expected to create Rs 28.5 lakh crore worth of additional output and generate over 6.4 million jobs. The response appears to be overwhelming and as per reports, it has attracted Rs 2.3 lakh crore ($30 billion) covering over 14 sectors.

Market Mechanisms Better

The selection of industries and individual parties is best left to the market mechanism rather than case-by-case government approval. ‘Government knows best’ narrative is the antithesis of the market economy. Experts caution that discredited License Permit Raj must not reappear. A good number of beneficiaries are already large-scale industries and shouldn’t need financial incentives.

In fact, many highly innovative Indian start-ups have gone global without any government incentives. Of course, some are facing rough weather due to unsustainable valuations, drying global liquidity. Even if some of them were to fold up, as they would, there is no cost to the exchequer.

Lift Productivity

We urgently need effective interventions to exponentially enhance labour and capital productivity. For example, South Korea’s electronics manufacturing productivity is 18 times higher than India’s. Similarly, their chemical manufacturing is a whopping 30 times more productive. With globally high capital/output ratios, India may need more than a trillion-dollar investment in manufacturing to double its share in the next 5 years.

It is imperative that we have interventions to help achieve exponential enhancement of productivity to the global best-in-class level and bring down the high level of capital/output ratio. The proposed incentives must not be used to mask these productivity shortfalls. Otherwise, investments in manufacturing are not sustainable and remain a dream.

Raise the Bar

Programmes like PLI may help in the short term but are not sufficient for India to become a global economic powerhouse. We need to raise the bar so as to emerge as a global economic power. Scale and global competitiveness are among the key drivers and they often come in pairs.

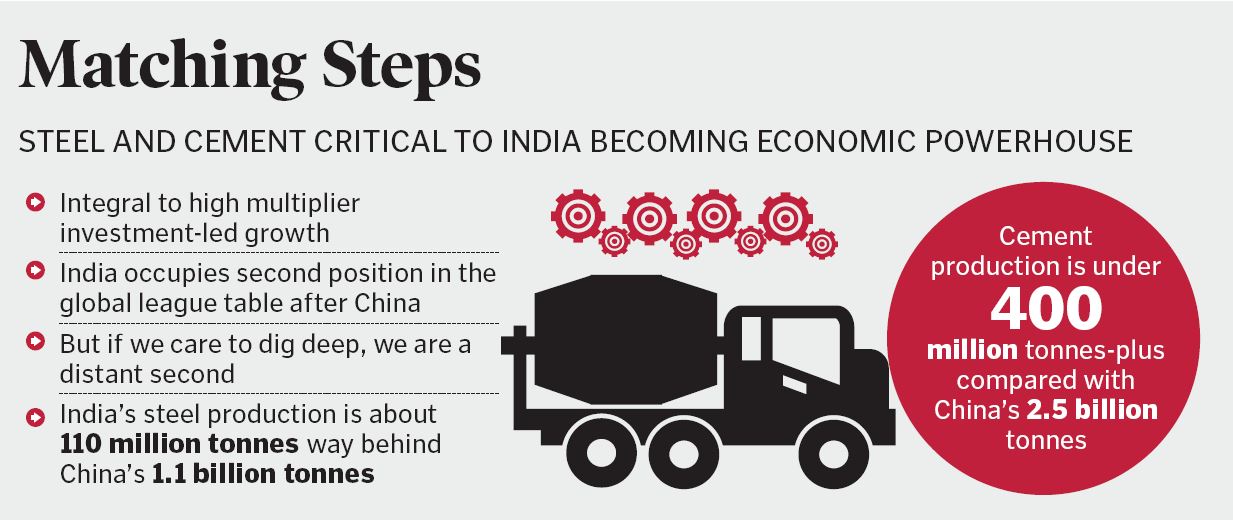

Globally construction is a $12-trillion industry and primacy in steel and cement gives India a pole position (see infographics). If the two industries achieve global scales and get recognition like IT, the chances of emergence as a global economic powerhouse in the next two decades come that much nearer. We can leapfrog as developed countries are facing Green (ESG)Tech retrofit challenges.

Global Scale not Utopian

We have some global-scale examples. Our two-wheelers industry is the world’s largest. The world’s largest Solar Park (Rajasthan 14,000 acres) and the largest Integrated Renewable Energy Storage Project (Andhra Pradesh 5,320 MW) are being set up in India.

Make in India is not just about manufacturing but services as well. Three of the world’s largest digital platforms (Aadhaar, UPI, CoWin) are in India and locally made. Similarly, ONDC (open network for digital commerce) being set up has the potential to emerge as the largest e-commerce network. Unlike other countries, these are public goods and at the same time have proved their worth in the marketplace. All these work at the citizen scale. India is well placed to give the world a global PHYSITAL (Physical plus Digital) economy model.

Manufacturing not Monolithic

Manufacturing was once synonymous with large-scale employment generation. But not necessarily so in the new economy. A McKinsey report reminds policymakers that manufacturing is not monolithic. There are broadly 4-5 categories from a policy perspective: capital-intensive industries like food and beverages, chemicals, petroleum, basic metals; labour-intensive like textiles, toys, jewellery, transport equipment; knowledge-intensive like computer, chip making, pharma, chemicals, medical; resource-intensive like mining, basic metals and petroleum; and value-intensive like electronics, precision engineering and medical devices.

Different Strokes

Employment potential, GDP intensity and strategic value, etc., vary widely among these categories and each category brings a different but important value to the table. According to a study, for instance, $1 billion of investment in textiles generates 1.5 lakh jobs and $4 billion would generate more jobs than the IT industry. But the IT industry creates high-value exports and a digital ecosystem which helps other industries. Similarly, defence manufacturing has strategic and geopolitical importance. Chip-making helps in global play and economic strategy but may not be highly employment-intensive. We need to map these different categories in terms of value, scale, employment and integration to global value chains. One size fits all interventions may not work.

Chinese Model not Replicable

China has become something of a legend in manufacturing and earned the sobriquet Factory of the World. But that model is not replicable in India. China provided cheap capital, cheap land, cheap labour for long periods of time consistently. This manifests in ease of doing business. For instance, the entire land is owned by the government and entrepreneurs have little problem accessing the land. The land pooling model of Amaravati is quite innovative. We need to design our own model.

It is not as though it is a choice between manufacturing and services sectors. Manufacturing also consumes a lot of services and creates indirect service jobs. We must equally focus on the potential for high- end services sector, which many startups are pursuing with intense innovation. Legal, medical, business consultancy, accountancy have the potential to achieve global scale.

Even during the Covid years, India could attract over $100 billion FDI and this is some testament to the growth story. China specialist Kishore Mahbubani said in an interview that India is in a sweet spot and many countries are courting it. But we don’t need social distractions. Democracy, Diversity and Decentralisation are assets, not liabilities. They help, not hinder.

Political power and influence in global affairs are derived from economic power and not the other way round. We must not let go of the wonderful opportunity to rewrite history — an economic one.

(The author is former Director and CEO, IDRBT, and Chairman of NPCI)

Related News

-

Chasing dreams, raring to go: Telangana IM Dhruva poised for greatness

5 hours ago -

Patna court refuses transit remand for Andhra police in IPS officer case

5 hours ago -

TTD to deploy advanced lab for laddu prasadam quality

5 hours ago -

Sports Briefs: Sports Shooting Conclave in city

5 hours ago -

India unveils first national counter-terrorism policy ‘Prahaar’

5 hours ago -

Supreme Court refuses plea on Tirumala laddu SIT review

5 hours ago -

Jawaharlal Nehru University protest against VC turns violent, student groups clash

5 hours ago -

Age is only a number for Vijay Kumar

5 hours ago