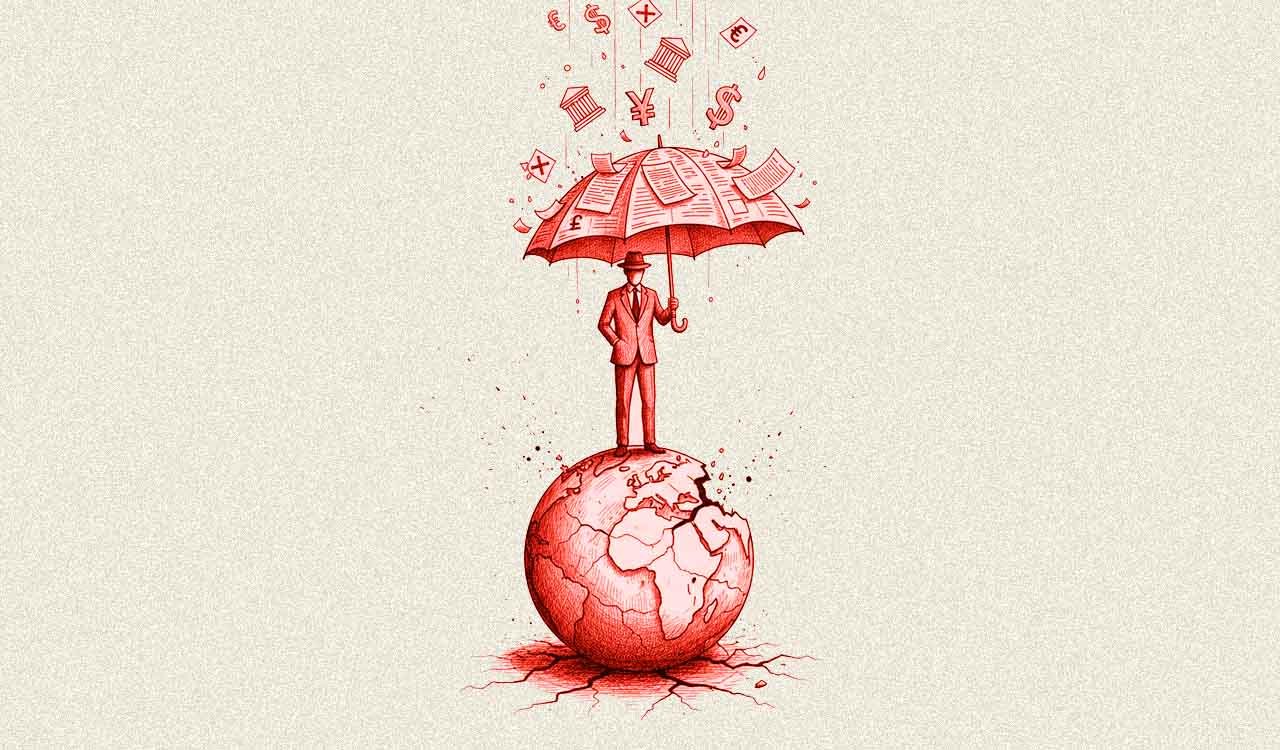

Opinion: Protecting profits from political risk

Having both political risk insurance and a bilateral treaty strengthens a company’s position in resolving cross-border disputes

By Dr Sukhamaya Swain, Dr Siddhartha Bhattacharya

Wars have become prolonged and frequent, with conflicts like the Russo-Ukraine war and the continuing crisis in the Middle East adding to global instability. Rising nationalism, political rhetoric, and climate-related challenges are further straining governments and governance. In this climate of uncertainty, humanity faces overlapping risks like economic crises, social tensions, environmental pressures, technological disruptions such as AI, and ongoing global wars.

Also Read

Yet, nations and companies continue to pursue growth and expansion, leaving themselves vulnerable to political instability. Since these risks are often driven by rising nationalism, social pressures, and international conflicts, the role of political risk insurance (PRI) becomes increasingly vital in managing and mitigating such uncertainties.

Pressing Risk

Political risk refers to the potential threats facing business operations that arise from political instability or shifts in government authority. While present worldwide, its scope and intensity vary across nations, and may result from government policy changes, such as modifications in exchange or interest rate controls. They can also emerge from actions taken by legitimate authorities, including the imposition of price controls, restrictions on currency transfers, or regulation of production and business activity. Additionally, political risk may stem from external events outside government control, such as war, revolution, terrorism, labour unrest, or extortion.

For globally active corporations and states, political risk remains a pressing concern. In the era of globalisation, expansion into international markets has become routine. However, the interplay of governance structures, regulatory regimes, protectionist policies, punitive taxation, and prevailing socioeconomic conditions significantly influences how foreign firms conduct business in host nations.

To mitigate potential financial losses from such challenges, companies often turn to PRI. This insurance typically covers threats such as expropriation, political violence, regime change, war, riots, sovereign debt default, and major legal or tax reforms. It is important, however, to distinguish political risk from economic risk; while the latter encompasses inflation, currency volatility, and financial crises, these do not fall under the scope of political risk.

Traditionally, foreign investment decisions have relied on tools like projected cash flow analysis, market surveys, econometric models, and comparative advantage assessments. Yet, these approaches often overlook the political and social transformations that can substantially impact investments. PRI emphasises the need to integrate such considerations and highlights the importance of theoretical frameworks that anticipate change, rather than relying solely on reactive measures (Simon, 1984).

In a world of wars, rising nationalism, and uncertainty, political risk insurance safeguards firms against losses, currency hurdles, and political violence

Finally, it is crucial to employ terminology specific to PRI with precision. Terms such as arbitration, breach of contract, civil strife damage, expropriation, inconvertibility, mediation, political risk, political risk management, and political violence damage hold distinct relevance for both insurers and insured parties in this context.

History

PRI originated during the US Marshall Plan in the Cold War era to protect multinational firms from uncontrollable losses abroad. Initially managed by the Export-Import Bank of Washington and later by USAID, it was institutionalised through the creation of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC).

The World Bank also established the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), with support from the International Finance Corporation (IFC). By the 1980s, private insurers entered the market, expanding PRI availability.

Issuers of PRI

PRI is offered by a wide range of issuers, broadly categorised into public, private, regional, and multilateral providers. Public insurers, such as OPIC (USA), ECGC (India), NEXI (Japan), Euler Hermes-PwC (Germany), OeKB (Austria), and Sinosure (China), act as intermediaries between governments and exporters.

Private insurers include both domestic firms like HDFC ERGO, Tata AIG and IFFCO Tokio in India and global players like Lloyd’s, Zurich, AIG, and Chubb. Regional and multilateral providers include institutions such as MIGA, the African Trade Insurance Agency, and the Inter-Arab Investment Guarantee Corporation, with MIGA notably playing a key role in resolving international disputes.

Elements of coverage

PRI differs from commercial risk insurance by covering non-commercial risks rather than operational or construction risks. Its main coverages include:

• Expropriation: Direct government actions like seizure or nationalisation, or indirect actions via laws that hinder normal business operations. Indirect expropriation scenarios are often unclear and critical for underwriters.

• Currency inconvertibility: Difficulties in converting local currency to foreign currency or transferring funds abroad.

• Political violence: Losses due to civil wars, revolutions, regime changes, or physical unrest.

Bilateral investment vs PRI

There is an ongoing debate on whether PRI or investment/bilateral treaties are more effective, though both typically cover similar risks. PRI is particularly recommended for investments in countries without bilateral treaties. Ideally, having both PRI and a treaty can strengthen a company’s position in dispute resolution. Empirical evidence linking PRI issuance or premiums to the presence of treaties is lacking, but logically, insurers may offer lower premiums when treaties exist.

Key differences between PRI and treaties include:

• Eligibility: Treaties cover specific listed investments, whereas PRI often targets exports.

• Damage calculation: Treaties calculate ex post via DCF (Discounted Cash Flow); PRI uses ex ante, based on net book value.

• Scope: PRI can include political violence or war; treaties have no settlement limits, PRI does.

• Settlement process: PRI settlements are between insurer and investor (with a cooling period), while treaty settlements can be lengthy due to multiple agencies and arbitration.

Given these differences, investors are advised to obtain PRI even if a bilateral treaty exists when doing business abroad.

Key instances

Several notable cases illustrate significant financial losses due to political events, highlighting the importance of PRI:

- GMR Infrastructure (2013-16): Forced to leave Male, initially sought USD 800 million in compensation; finally received USD 270 million after a prolonged dispute.

- Jindal Steel in Bolivia: Claimed USD 100 million for losses; awarded USD 22.5 million.

- Anglo-Iranian Company (1951): Lost all assets due to the nationalisation of Iran’s oil industry.

- Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline Beecham (2004): China revoked patents for Viagra and Avandia to promote local industry.

- American International School, Bamako, Mali (2012): Military coup led to temporary closure and reduced enrollment; losses estimated at USD 1.5 million. PRI via OPIC allowed recovery of USD 1.2 million.

These cases clearly underscore how PRI can mitigate financial damage from political instability, expropriation, or government interventions.

The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), established in 1965 under the World Bank, is an authority for resolving investment-related disputes. Its conciliation procedures carry official recognition, and its creation followed efforts by former World Bank President Eugene Black to mediate international investment conflicts.

As of 31 December 2024, ICSID had registered 1,022 arbitration and conciliation cases under the ICSID Convention and Additional Facility Rules. Since 1972, ICSID cases have been dominated by the oil, gas, and mining sectors (25 per cent), followed by electric power and other energy (17 per cent), other industries (11per cent), construction (10 per cent), transportation (9 per cent), and finance (8 per cent).

(The authors are Professors of Finance at JK Business School, Gurugram)

Related News

-

Malakpet police nab two-wheeler thief, recover 12 stolen motorcycles

34 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Fake MBBS admission racket busted in Ameerpet

45 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Land acquisition notifications issued for Gandhi Sarovar Project

59 mins ago -

Hyderabad Bird Atlas season 3 records highest-ever 214 species

1 hour ago -

YFLO celebrates 20 years of empowering women leaders

1 hour ago -

Ramzan or Ramadan? Understanding the difference

2 hours ago -

KTR demands Centre’s reply over Revanth’s claims of preparedness to send Rs 1,000 crore to AICC

2 hours ago -

Bail plea of BRS leader Balka Suman adjourned again

2 hours ago