Rewind: Lifting rivers, Media and Myth—Celebrating Andhra, questioning Telangana

While Andhra Pradesh’s irrigation projects are celebrated as ‘Sujala Sravanthi’, Telangana’s lift schemes face scepticism — exposing the asymmetry in media narratives and political discourse

By Chandri Raghava Reddy

It is heartening to watch the videos on social media of Krishna water reaching Kuppam in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh and filling the Parama Samudram Cheruvu, located nearly 700 km from the Pothireddypadu head regulator. Regardless of the region, the image of scarce water filling dried village tanks after traversing such a long distance from the Telangana border to the Tamil Nadu border areas is a moment of quiet triumph. In this journey, Krishna water fills several reservoirs en route, breathing life into drought-affected Rayalaseema.

Also Read

At a time when India is making significant strides in science, technology, and global diplomacy, ensuring water for farming still remains an elusive dream, leaving farmers to the vagaries of nature. However, there has been a series of significant measures in both Telugu States in either utilising or diverting water from the Krishna and the Godavari in the last two to three decades. Although Telangana’s initiatives began late, particularly post bifurcation, they not only gained momentum but achieved magnificent results in utilising Godavari and Krishna water to a great extent between 2014 and 2023.

Contrasting Narratives

This article does not aim to list the initiatives. Rather, it is about highlighting the contrasting narratives floated in the social media, aided by popular Telugu media, both print and electronic. What stands out, particularly to farmers and observers in Telangana, is the asymmetry in the narrative. For example, the Krishna water reaching Kuppam is widely celebrated and circulated in Andhra Pradesh. The overwhelming euphoria among farmers and the buoyancy within party cadres gained significant traction. Interestingly, this news was largely confined to the Andhra Pradesh region. Telangana newspapers and electronic media chose to ignore it.

For decades, Telangana farmers were told river water could not be harnessed due to altitude. Only after the formation of the State in 2014 did transformative initiatives begin. The Kaleshwaram Irrigation project lifted Godavari waters into North Telangana’s parched lands, redefining possibilities

In contrast, similar milestones in Telangana before 2023 were often met with scepticism, with questions raised in terms of their viability and necessity. The question thus arises: If irrigation water is universally acknowledged as the lifeline of farmers, irrespective of regions, why are such milestones celebrated with Jalaharathi in Andhra Pradesh, yet berated in Telangana?

The cost-benefit analysis, electricity expenditure, and even laws concerning transferring water outside river basins are rarely raised in the context of Andhra Pradesh. However, when it comes to Telangana, farmers’ interests are often overlooked, and the media does not hesitate to float narratives, ranging from casting aspersions on those in power to discussing climate change. These narratives have gone so far as to stigmatise paddy as a “water guzzler,” suggesting that its cultivation should be strongly discouraged.

Had the State not been divided, these narratives would have gone to the extent of suggesting that Telangana farmers lack knowledge about cultivation and, therefore, do not require water for irrigation. Yet, the world has seen the reality of Telangana farmers’ potential, as the State became number one in paddy procurement in just five years. In fact, some intellectuals also floated the idea of discouraging Telangana farmers from cultivating paddy, arguing that since rice consumption is declining due to diabetes, making water available for them is unnecessary.

Telangana farmers, however, insist that government agencies must find alternative uses for rice procured rather than asking them to stop cultivating paddy. Moreover, if agricultural commodities such as cereals, pulses, vegetables, and fruits get the same support as that of paddy, farmers would not hesitate to diversify their crops.

Same Goals, Different Realities

Irrigation initiatives in Andhra Pradesh are not fundamentally different from those in Telangana. Both States aim to bring water to drought-prone regions. However, the similarities end there. Telangana farmers highlight three key concerns:

- The surplus myth: Andhra Pradesh claims its projects use flood or surplus water from the Srisailam reservoir. Telangana farmers dispute this, pointing out that districts like Mahbubnagar, Nalgonda, Ranga Reddy, and Hyderabad — within the Krishna basin — still face unmet irrigation and drinking water needs, questioning the ‘surplus’ tag.

- Framing matters: While Andhra Pradesh’s Handri-Neeva Sujala Sravanthi and Galeru-Nagari Sujala Sravanthi, and Telangana’s Kaleshwaram are lift irrigation projects, the framing differs. In AP, they are poetically labelled Sujala Sravanthi, creating a positive vibe. In Telangana, they are labelled as lift irrigation schemes, conveying the message that they are financial burdens.

- Selective Celebrations: Andhra Pradesh’s Jalaharathi, celebrating water reaching Kuppam, contrasts sharply with Telangana’s Kaleshwaram, which, despite irrigating vast areas, received little fanfare.

Demanding Justice, Not Charity

For decades, Telangana farmers were told that the river water could not be utilised due to its altitude. They were left to the mercy of nature, erratic monsoons, dry borewells, and political indifference, forcing generations to migrate or abandon agriculture. Though there were half-hearted efforts, stalled or incomplete projects prevailed. It was only after Telangana’s formation in 2014 that transformative initiatives began. The Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Scheme marked a symbolic shift, for the first time, lifting Godavari waters into North Telangana’s parched lands and redefining agricultural possibilities.

A new generation of Telangana youth now harbours hopes on agriculture, not out of desperation, but aspiration. Educated, tech-savvy, and deeply rooted in their regional identity, they now see farming as a calling, empowered by direct cash transfers through Rythu Bandhu and Bharosa, 24-hour free electricity, abundant water from projects like Kaleshwaram, and targeted interventions. Yet, they are also asking critical questions: Why did it take so long? Why were we denied what others received as a matter of course?

Recalling the Telangana statehood movement, which centred on neellu, nidhulu, niyamakaalu (water, funds, and employment), the rural youth are closely monitoring the State’s efforts to harness Godavari and Krishna waters. Having grown up witnessing their parents’ hardships in agriculture and listening to their grandparents’ stories of struggles with water scarcity, often leading to crippling debts and migration, they carry these memories deeply. Visuals of emptied villages, with parents working elsewhere and children left with ageing grandparents, remain vivid.

Today, rural youth are demanding answers about the ‘organised’ opposition to utilising Godavari waters and safeguarding Telangana’s shares in both the Godavari and Krishna rivers. Despite historical injustices, no major projects have effectively harnessed these rivers in the last 60 years. Frustration grows over the lack of media narratives on Andhra Pradesh’s Sujala Sravanthi projects, which are rarely subjected to debates on economic viability, cost-benefit analysis, power burdens, land acquisition, DPRs, or, most critically, diversions outside river basins. This generation knows its rightful share of Krishna and Godavari waters and critically analyses the stances of political parties and organisations claiming to champion Telangana’s interests. They demand politics for farmers’ welfare, not politics with farmers.

The journey of Krishna and Godavari waters into drought-prone regions is not a gift from the state. They are the right of every farmer in modern India. One may celebrate irrigation milestones in Andhra Pradesh, but Telangana’s equally significant efforts cannot be subjected to scepticism and guilt. This imbalance in narrative reflects an entrenched hegemony in media, politics, and institutions, still operating, regrettably, from Hyderabad.

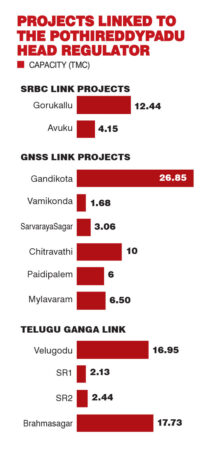

A snapshot of the two major schemes in Andhra Pradesh

- Galeru-Nagari Sujala Sravanthi Project

Among the two major Sujala Sravanthi projects launched in united Andhra Pradesh, the Galeru-Nagari Sujala Sravanthi Project (GNSS) is a vital lift irrigation scheme for the drought-prone Rayalaseema region. It began with a humble design to divert ‘surplus’ floodwaters from the Krishna river through the Srisailam Right Bank Canal (SRBC) starting at Pothyreddypadu. A 334-km canal network irrigates ‘drought-prone regions’ across Kadapa, Chittoor, and Nellore districts. The project uses ‘lift irrigation infrastructure, including electric pumps’ to lift water to higher altitudes.

At the first point, the Pothireddypadu Head Regulator, the high-capacity vertical turbine pumps divert water from the Srisailam Reservoir into the Telugu Ganga main canal, SRBC, and GNSS systems. At the Gandikota Reservoir Lift Station, the project’s central lift point, water is lifted into the main GNSS canal. Further downstream, the Kaletivagu Lift Point is integrated with the Handri-Neeva Sujala Sravanthi (HNSS) system, pumping water toward the Veligallu Reservoir and nearby village tanks.

Other reservoirs and pumping stations under this project include the Veligallu Reservoir Pumping Station, Sri Balaji Reservoir, and the Mallemadugu Reservoir.

On the SRBC link, the Gorukallu Reservoir Lift acts as a balancing reservoir, channelling water into Avuku and other tanks. Within the Telugu Ganga link, the Velugodu Balancing Reservoir is the staging point where water is lifted to reservoirs like SR1, SR2, and Brahmasagar. Of these, the Brahmasagar Reservoir is the final major lift point, supplying much-needed irrigation to farmlands in Kadapa district.

- Handri-Neeva Sujala Sravanthi

It is the second ambitious lift irrigation initiative aimed at supplying irrigation water to the Rayalaseema region by diverting ‘surplus’ water from the Srisailam Reservoir to irrigate farm lands across Kurnool, Anantapur, Kadapa, and Chittoor districts. The canal spans about 565 km and has about 12 lifts, pumping water to a height of about 370 metres. The project is supported by 43 pump houses and 269 pump-motor units.

The Mutchumarri Lift Scheme plays a key role — drawing water with 12 pumps feeding the HNSS and four pumps supplying the KC (Kurnool-Cuddapah) Canal. The project also includes eight balancing reservoirs —notably Jeedipalli, Maddikera, and Adavipalli—along with five tunnels with a length of 13.05 km through the hilly terrain. It was designed for a 55-cusecs canal capacity, but now the canal is being widened from 11 m to about 20 m to handle 109 cusecs.

It is important to note that the Galeru-Nagari and Handri-Neeva Sujala Sravanthi projects are lift irrigation schemes, but the media narrative highlights the phrase Sujala Sravanthi to evoke piety. Their reliance on huge electric pumps, balancing reservoirs, and tunnel infrastructure clearly demonstrates that these two are nothing but lift-based irrigation projects and not gravity-based fed irrigation initiatives.

(The author is Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad)

Related News

-

KTR seeks SEC intervention over attacks and false votes in civic elections

58 seconds ago -

Balka Suman accuses Vivek of mocking democracy in Kyathanpalli

19 mins ago -

Congress-BJP nexus exposed in civic polls; BRS stalled despite majority mandate

32 mins ago -

Pentagon may cut ties with Anthropic over AI use limits

49 mins ago -

Supreme Court issues notice on 2023 data protection law plea

56 mins ago -

Delhi Police marks 79th Raising Day, Amit Shah praises force

1 hour ago -

EC suspends seven West Bengal officials over SIR misconduct

1 hour ago -

BRS wins Jammikunta Municipal Chairman post with 16 votes

1 hour ago