Sensor and Sensibility

The sensor realist mode both relies on and exceeds the military technology geared towards dehumanisation

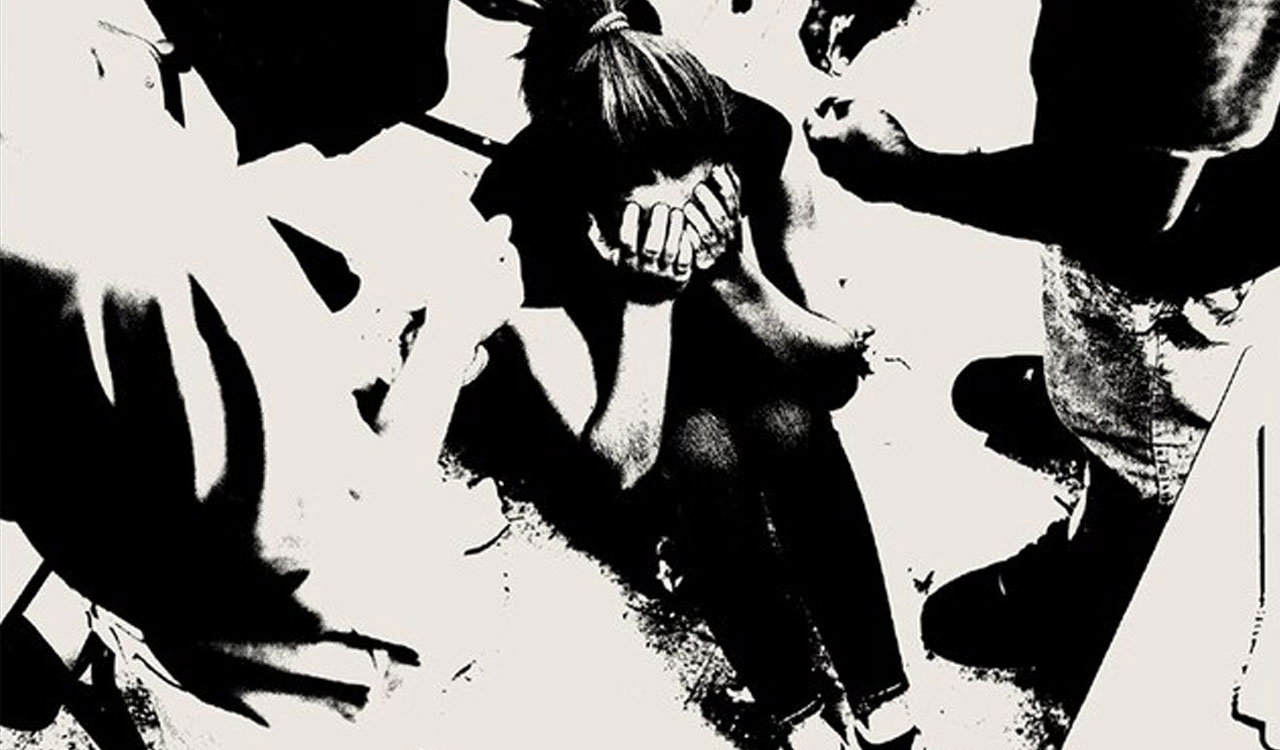

In his 52-minute multiple award-winning video installation, Incoming, photographer Richard Mosse literally spectralises a people whom societies and governments do not want to see, and would rather render invisible: refugees.

Mosse first filmed the refugees trekking across the hostile lands of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and other hotspots. Refugees are tracked fleeing from Syria through Turkey into Europe. Another sequence follows African migrants crossing the Sahara Desert to Libya, then on to Sicily and finally reaching Calais, France.

It is not the filming per se but the equipment he employed that arrests us. Mosse used military grade surveillance cameras that can pick up heat signatures from bodies at a distance of 30 km, under almost any condition. The camera is 23 kg in weight and cannot be carried around easily, for obvious reasons, and has to be remotely operated. The camera is classified as a weapon by international law, since it is often linked to weaponry for long-distance attacks. Using this camera, Mosse created his first series, Heat Maps.

A Military Aesthetic?

The idea of a military aesthetic seems a contradiction in terms: the military is everything that an aesthetic is not, one would think. What Mosse does is to employ surveillance and governance structures – informational and visual governance – to point to moments and stages of global suffering.

Recalling the work of the architect-philosopher Paul Virilio writing about military bunkers and the sightlines of rifle-scopes, Mosse shows us the ‘faces’ of those buried in anonymity. Virilio argued that with the excessive use of cameras and visual imaging equipment, we can only see through and with technology therefore lose all practices of direct observation. With this, argues Virilio, we also lose the sense of the material nature of whatever we are observing.

‘Totalitarianism’, he said, ‘is latent in technology’. Virilio further argued – and this interests us here – that with contemporary warfare, the camera or vision machine is interested in speed of movement than in position.

Mosse’s work, without referencing Virilio, seems to turn these militaristic processes on their head. By capturing their ‘heat signatures’ and movement with the camera, Mosse uncovers the humanity of refugees. These are ‘warm’ bodies, and not just statistics, the film based on the video installation suggests. Since these are heat signatures, we can only see the humans as ghosts on the screen. But we understand that the heat maps are maps of material bodies, suffering, in pain and traumatised, and yet producing heat even as the heat dwindles in their dying frames.

The military surveillance, which registers the refugees as threats, masses and contagion, is counterpoised with the singularity of our recognition: that the ghostly images are signs that the people are alive, their bodies have heat. Aesthetically, this resembles ghost photography (the subject of many pop films devoted to the paranormal) and forces us to rethink ideas of how we can represent the human in extremis.

Sensor Realism

Scholars Rune Saugmann, Frank Möller and Rasmus Bellmer propose a theory of ‘sensor realism’. For them, sensor realism is ‘a vision of reality as it takes place in sensing and in the production and visualisation of sensing data’. They elaborate:

‘Sensor realism thus designates a visual realism specifically engaging the data production and visualisation practices of sensor societies by depicting with a high degree of verisimilitude how sensor data is visualised and makes reality available to sensor observers and operators. Sensor realism opens up for discussions the relationships between reality, sensing, sensor data, data processing and visualisation, and security practice, and the often mutual reconfigurations happening in these relationships.’

Mosse demonstrates how the sensors developed to target ‘undesirables’ and destroy them, may be employed in an entirely different key and to very different ends. It is data visualised in realistic but technologically mediated ‘frames’ but it is also data humanised, in Mosse’s hands.

Mosse says many of the refugees die in the course of their ‘perilous’ march, of hypothermia or drowning. So ‘heat is a crucial sort of metaphor’ in his work and for what it means to die of the cold, when being filmed by heat-seeking camera and sensors. Mosse adds that these imaging devices are actually ‘dehumanising’ when they film a ‘biological trace’ of the human rather than the individual. He is attempting, to solve a ‘narrative dilemma’: is this kind of filming an intrusion into their privacy, or would it be better to ‘brush it under the carpet’ and look the other way? For Mosse, he is trying to capture their individuality without either dehumanising them or identifying them.

The sensor realist mode both relies on and exceeds the military technology geared towards dehumanisation. What is important is that the visualisation and datafication that reconfigures the human in the ‘apparatus’ of security systems, governance mechanisms and massive quantum of data, underwritten by codes and algorithms – what is commonly called today algorithmic governance – is reinscribed in the film and the video installation (Incoming was displayed at the Barbican).

That is, the same data placed in an entirely different apparatus – a public space, a museum, a court of law – and within a different technology of viewing, can alter the perception of the refugees. If, as commentators argue, reality is co-constructed within technologies such as the camera, they are also constructed within technologies of viewing.

Sensoribility

When Mosse reprises the military camera for ‘shooting’ the refugees rather than targeting them (stage 1) and then places these ‘shots’ not in a military surveillance room but for public viewing and on techno-social platforms such as YouTube (stage 2), he has given a whole new set of meanings to the ‘bodies’ on the screen.

Mosse shocks and alerts us to the possibilities of technology. Surveillance and targeting from 30 km away, is morphed in his hands into a humanitarian scopic regime. Sensors produce data, bodies and identities. Sensory realism modifies this to draw attention to the frames in which these are produced.

Mosse, balanced precariously between voyeuristic displays of dehumanised suffering and the humanitarian project of depicting suffering, calls for a shift in our technologically determined perception towards a sensoribility.

(The author is Professor, Department of English, University of Hyderabad)

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

KTR raises concern over safety lapses at Santosh Nagar–Chanchalguda steel bridge construction site

-

Afghanistan’s India tour: Test match and ODI series announced

-

Engineering college student reportedly drugged and assaulted in Telangana

-

Quthbullapur revenue official caught taking Rs 15,000 bribe by ACB

-

Lunar eclipse: Tirupati temples shut, darshan resumes at 8.30 pm

34 seconds ago -

Harish Rao alleges massive illegal quarrying in Hyderabad by Minister Ponguleti’s firm

7 mins ago -

US to unveils plan to manage oil prices amid strikes on Iran

12 mins ago -

Vemulawada temple, other temples in Karimnagar closed on account of lunar eclipse

43 mins ago -

Telangana High Court hears Kaleshwaram commission pleas

8 hours ago -

Shrine relocation row: Telangana HC declines interim relief

8 hours ago -

Lionel Messi, Telasco Segovia rally Inter Miami to 4-2 victory over Orlando City

9 hours ago -

India and England set for thrilling T20 World Cup semi-final at Wankhede

9 hours ago