From 150 to 300: How Data-driven delimitation is redefining service delivery in Hyderabad

To improve urban service delivery, the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) proposes doubling its wards from 150 to 300. This reform addresses Hyderabad’s expansion to nearly 2,000 sq km. By creating manageable units, the city aims to enhance political representation, integrate GIS-based data analytics, and align with UN Sustainable Development Goals for inclusive growth. This approach ensures data-driven governance puts citizens "centre stage".

What’s in a Ward?

GHMC Delimitation from 150 to 300 Wards – Governance, Data Analytics and Urban Service Delivery

More Than Lines on a Map

William Shakespeare’s famous line, “What’s in a name?”, finds an unexpected echo in Hyderabad’s ward delimitation debate. Whether Safilguda is called Vinayaknagar or any other name, citizens still experience the same roads, water supply, power cuts, drains, and potholes. Yet, how a city is divided into wards functionally influences how effectively these everyday services are planned, delivered, and monitored.

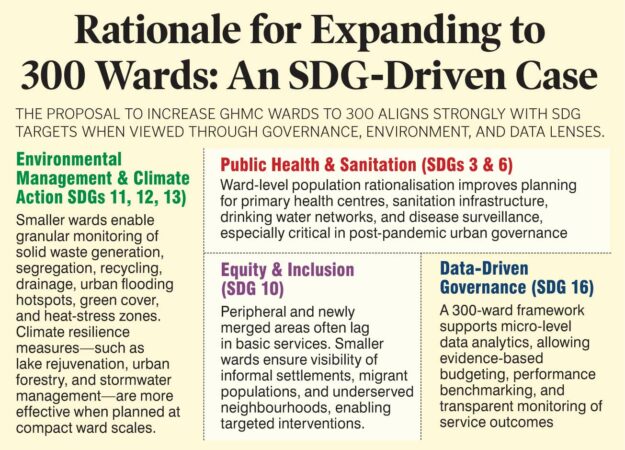

At its core, ward delimitation shapes how cities plan, allocate resources, manage environmental assets, deliver basic services, and ensure inclusive growth—directly aligning with UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and its interlinkages with SDGs 3 (Health), 6 (Water & Sanitation), 9 (Infrastructure), 10 (Reduced Inequalities), 12 (Responsible Consumption), 13 (Climate Action), and 16 (Institutions).

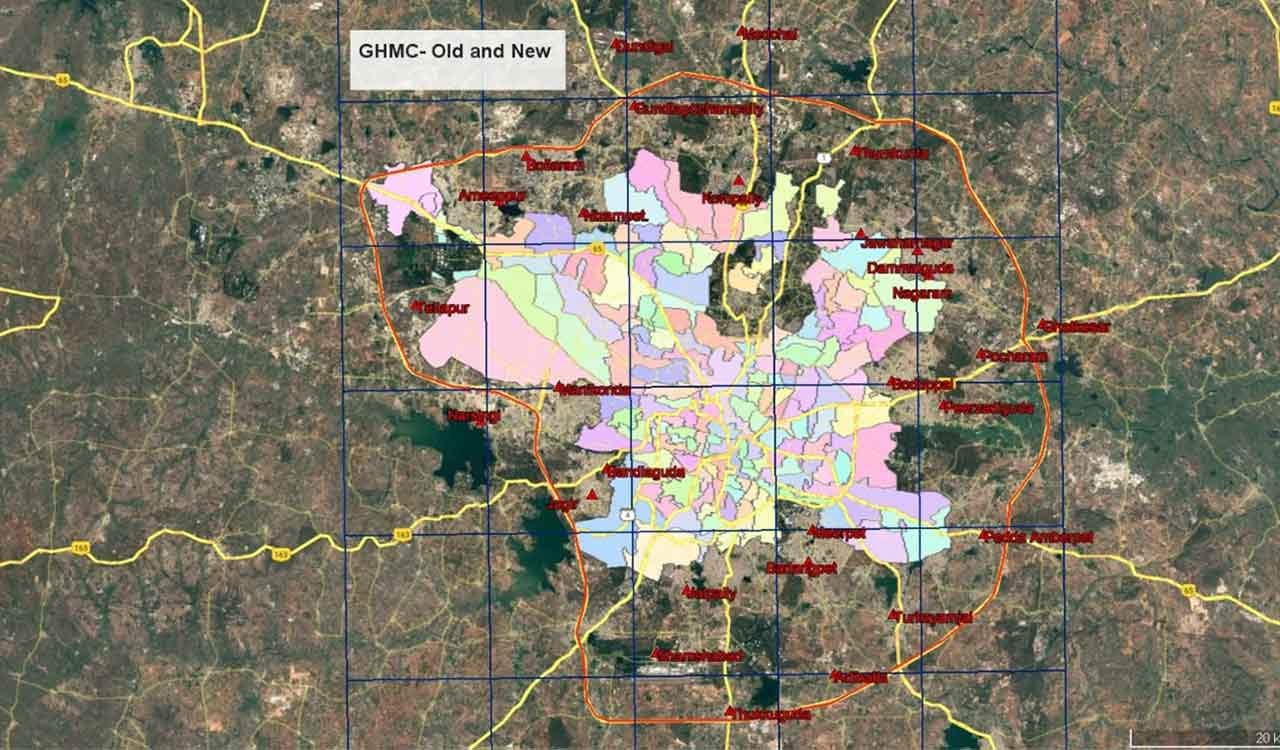

The proposal to increase the number of wards in the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) from 150 to 300 is therefore not a routine administrative or electoral adjustment. It is a structural reform with implications for governance efficiency, political representation, environmental management, and the use of data and technology in city administration. Hyderabad has expanded far beyond its historical municipal limits. With the merger of 27 peripheral Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and growth up to and beyond the Outer Ring Road (ORR), GHMC’s functional urban area has expanded from about 650 sq km to nearly 2,000 sq km. Managing this vast, diverse, and rapidly changing urban region with an unchanged ward structure is increasingly untenable.

Genesis of the Ward System in India

In India, the ward has traditionally been the basic unit of urban governance and planning. The idea was simple but powerful: divide cities into manageable geographic units with broadly comparable populations to enable:

• Equitable political representation

• Fair allocation of municipal resources

• Micro-level planning, monitoring, and accountability

Though conceived long before the SDGs, the ward system intuitively reflects SDG thinking—localised planning, equity in service delivery, and decentralised decision-making.

Early municipal thinking assumed that a ward with around 20,000 population was administratively manageable. As cities expanded, ward populations rose sharply. By the 2011 Census, ward populations in major cities typically ranged between 40,000 and 60,000, and in some cases much higher. An often-overlooked but important design principle was that wards were numbered, not named. This avoided confusion when wards were subdivided during future delimitation exercises. Names linked to landmarks or personalities could easily become problematic if those features fell into a different ward after redrawing boundaries.

GHMC’s Evolution: From MCH to a Mega Metropolitan Body

Hyderabad offers a clear illustration of how ward structures evolve with city growth:

• Pre-2007 (MCH era): 24 wards, ~173 sq km area, ~35 lakh population, with an average ward population of ~1.46 lakh.

• Post-2007 (GHMC formation): Merger of 13 municipalities expanded the city to ~650 sq km, ~67 lakh population, and 150 wards, reducing the average ward population to ~45,000.

• Current context: Population estimates nearing one crore, with average ward population again rising to 60,000–70,000, alongside major spatial expansion.

The latest phase of growth, driven by the inclusion of 27 peripheral ULBs, is geographically uneven. Expansion is far more pronounced in the southern and eastern corridors, while the western and northern parts remain relatively compact. Retaining only 150 wards under these conditions would result in very large, heterogeneous wards, making effective governance and service delivery increasingly difficult.

A look at the map shows that the new expansion is largely driven by the contours of ORR. 8 ULBs in the south, 8 ULBs in the East,7 in the North and 4 in the West make up the Mega Metro Hyderabad. The area is about 2000 sq kms. The existing 150 wards are overlaid on the satellite imagery.

Why 300 Wards? Governance and Service Delivery

The proposal to expand GHMC to 300 wards is driven by multiple, interlinked governance considerations of administrative efficiency, equitable representation, improved service delivery and citizen engagement. Smaller wards allow closer supervision of field staff, quicker grievance redressal, and clearer accountability. Ward officers and elected representatives can realistically engage with citizens only when geographic and population sizes are manageable.Population densities vary widely across Hyderabad.

Doubling the number of wards helps move closer to the principle of “one councillor, roughly equal population”, strengthening local democracy.Municipal services—sanitation, solid waste management, water supply, sewerage, roads, street lighting, primary health, and urban amenities—are inherently location-specific. Compact wards are easier to plan, monitor, and evaluate. Residents relate more easily to smaller, coherent neighbourhood units. Compact wards encourage participation by Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), community groups, and civil society in planning and monitoring services.

Political Ramifications

Ward delimitation inevitably carries political consequences of increase in the numbere of public representatives / corporators, changes in electoral arithmetic and party strategies.Boundary changes can reshape demographic compositions, influencing electoral outcomes.Peripheral areas that were previously under-represented may gain a stronger political voice.

When undertaken transparently and scientifically, delimitation strengthens grassroots democracy. Problems arise when colonies are split across multiple wards, natural or social boundaries are ignored, or citizens and RWAs are inadequately consulted.

How Hyderabad Compares with Other Metros

A comparison with other Indian metropolitan cities puts the proposal in perspective:

• Delhi (MCD): Over 250 wards for a dense but relatively compact urban area.

• Mumbai (BMC): 227 wards, each supported by a strong administrative structure.

• Bengaluru (BBMP): 198 wards, widely considered insufficient for its spatial sprawl.

• Chennai (GCC): 200 wards for about 426 sq km.

Given Hyderabad’s rapid outward growth and metropolitan character, 300 wards is neither excessive nor unprecedented. But then a case in point is can we have a ward as a uniform unit –across the country ? This could pave the way for better planning and allocation of resources across the 85000 wards in the 4500 plus urban local bodies in the country.

Uniform Geographic Units: The Case for Integration

One of the most persistent citizen complaints during public consultations is the lack of alignment between ward boundaries and departmental jurisdictions. A single colony may fall under:

• One GHMC ward

• A different police station

• Another electricity (TRANSCO, GENCO ) division

• A separate water board or revenue jurisdiction

This fragmentation creates confusion, weakens accountability, and complicates grievance redressal. How about GHMC hierarchy ,with its mandate of delivering 18 different categories, of wards- circles- zones being accepted by all other departments which could ensure convergence of resources, management, decision making, leadership and service delivery. Treat the GHMC ward as the base geographic unit for all citizen-facing data and services and mandate theother service providers to aggregate wards where larger operational units are required (police circles, health zones, education divisions). Use of mapping tools / GIS based ward maps across departments will usher in a informed “decision support system”.This “single geography, multiple administrative layers” approach can significantly improve coordination and service outcomes.

Data Analytics and the Role of GIS

Every urban service ultimately revolves around one question: “Where?”Where are drains missing? Where are garbage vulnerable points? Where are water shortages recurring? Where are health risks concentrated?

A GIS-based ward delimitation and management system enables:

• Scientific boundary definition using roads, natural features, drainage basins, and settlement patterns

• Avoidance of colony fragmentation and jurisdictional overlaps

• Integration of door numbering, asset inventories, service complaints, and field data

At the ward level, data analytics can support:

• Correlation of population density with waste generation and collection efficiency

• Mapping of disease incidence with sanitation and water infrastructure gaps

• Identification of flooding hotspots using elevation and drainage data

• Performance benchmarking of wards on response times and service coverage

With access to high-resolution satellite imagery and national platforms such as Bhuvan (NRSC), Hyderabad is well placed to institutionalise ward-level dashboards for evidence-based decision-making.

Beyond Numbers and Names

The proposed increase from 150 to 300 wards should not be viewed merely as an electoral expansion or a renaming exercise. It is an opportunity to modernise ward-level governance, strengthen political representation, and embed data-driven decision-making into everyday urban management.If backed by scientific delimitation, GIS integration, data analytics, and structured public consultation, the reform can become a model for metropolitan governance in India. If treated mechanically, it risks multiplying existing inefficiencies. Ultimately, wards are not just lines on a map or names on a list—they are the operational building blocks of urban governance and the lived experience of city residents.

Shakespeare also wrote famously “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players” The Landscape of Hyderabad too has many actors- politicians, bureaucrats, activists- but the citizen for whom all these performers work must be put centre stage, therein lies the mantra for true & functional governance.

Authors:

Major (Dr.) G. Shiva Kiran, Environment & GIS Consultant | Urban Governance Specialist

Sunandani Guntur, Project Analyst with Cal Bio, California, USA

Sunethra Guntur, Senior Data Analyst at CVS, USA

Related News

-

After top court blow, Trump seeks 15% global import tariff

4 hours ago -

One year on, no closure for SLBC victims’ families

4 hours ago -

India face South Africa in crucial T20 World Cup Super Eight clash

5 hours ago -

Rain forces washout in New Zealand-Pakistan T20 World Cup match

5 hours ago -

Hyderabad’s Nehru Zoological Park welcomes real-life ‘Rafikis’

5 hours ago -

India clinch first Women’s T20I series victory in Australia since 2016

5 hours ago -

Sowmya selected for Indian women’s football team for AFC Cup 2026

5 hours ago -

Lohitha Sai wins girls’ recurve gold at CM Cup archery

5 hours ago