Maa Bhoomi’s legacy: A powerful commentary on feudalism, revolution and fight for justice

The article analyses the iconic 1979 Telugu film ‘Maa Bhoomi’, set against the backdrop of the Telangana Armed Struggle in the 1940s. It explores the themes of social inequality, feudalism, and class struggle, highlighting the brutal conditions faced by the landless peasants.

When one watches Charlie Chaplin movies in the backdrop of the Great Depression, they tend to leave the viewer with the feeling that humans, essentially, are humans, regardless of the centuries of time that elapses between generations. It’s the same emotions of greed, hunger, desperation, jealousy, and whatnot, that plagued the human mind back then and now.

The same is with the legendary Telugu movie ‘Maa Bhoomi’, released in 1979. Set in the rural backdrop of the now-fluoride-hit villages in the Nalgonda district of Telangana, the story takes place around the time of the Telangana Armed Struggle of the 1940s.

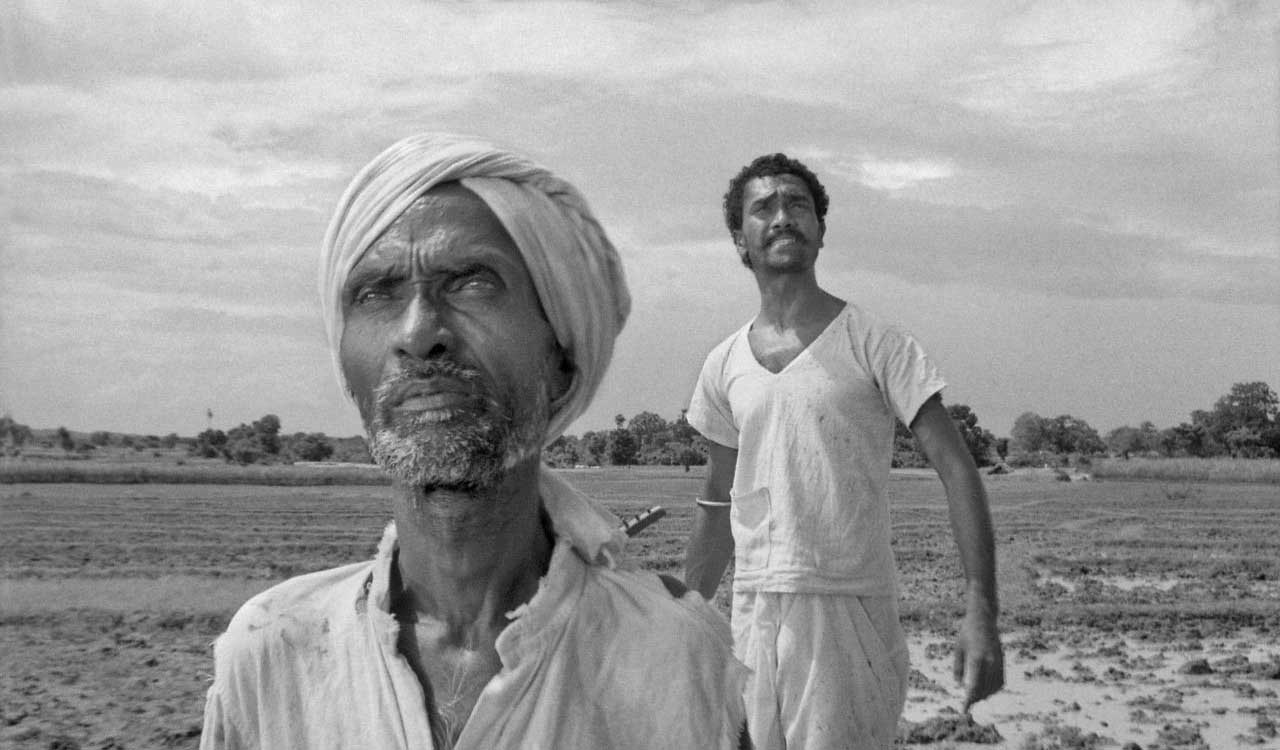

The film gives a glimpse into the socio-economic conditions of the time that led to the violent movement, which can probably be termed as the first left-wing-extremist movement of the country, about thirty years before the Naxalbari movement. It starts off with Ramayya, a young boy, a son of a landless peasant, being asked by the Dora’s (the feudal zamindar/jagirdar) henchman, to start herding their cows. What follows this is a gut-wrenching song that talks about the tender age of the young lad, emphasising on the fact that the new serf is a child who was weaned off of milk just recently.

The first few minutes of the film really hammer in the hard differences between those who have and those who don’t. The Dora has an army of people to cater to his every need, from ensuring he is well groomed to running his Jagir, maintaining his palatial Gadi (haveli). On the other hand, the peasants who work for him are often clothed only in a torn loincloth, without any footwear, relishing their rice gruel flavoured with betel leaves, the only luxury that they can afford.

The Dora does not care for the people under his rule, beyond abusing them for taxes and squeezing every last ounce of life out of them through hard labour. The brutality of this is depicted hard when a labourer asks permission to breastfeed her child and the labour-boss demands her to show whether her breasts really have milk or not, and he spits on the ground, telling her to return before the spit dries out. This movie is definitely not for the faint-hearted.

The Dora’s son is no less, as he wants a new bird (fresh woman, for the lack of a better description) to satisfy the Nizami official that he is shown wining and dining for favours. The Nizami official relishes Red Label scotch while henchmen are sent to bring a newly-wed woman from the village for him. While all of this is going on one side, there’s also a subtle questioning attitude that grows amongst the villagers, as they hear of the communist Sanghams that help the villagers against the Doras. However, they do not have the courage to talk to the Sanghams about their village yet.

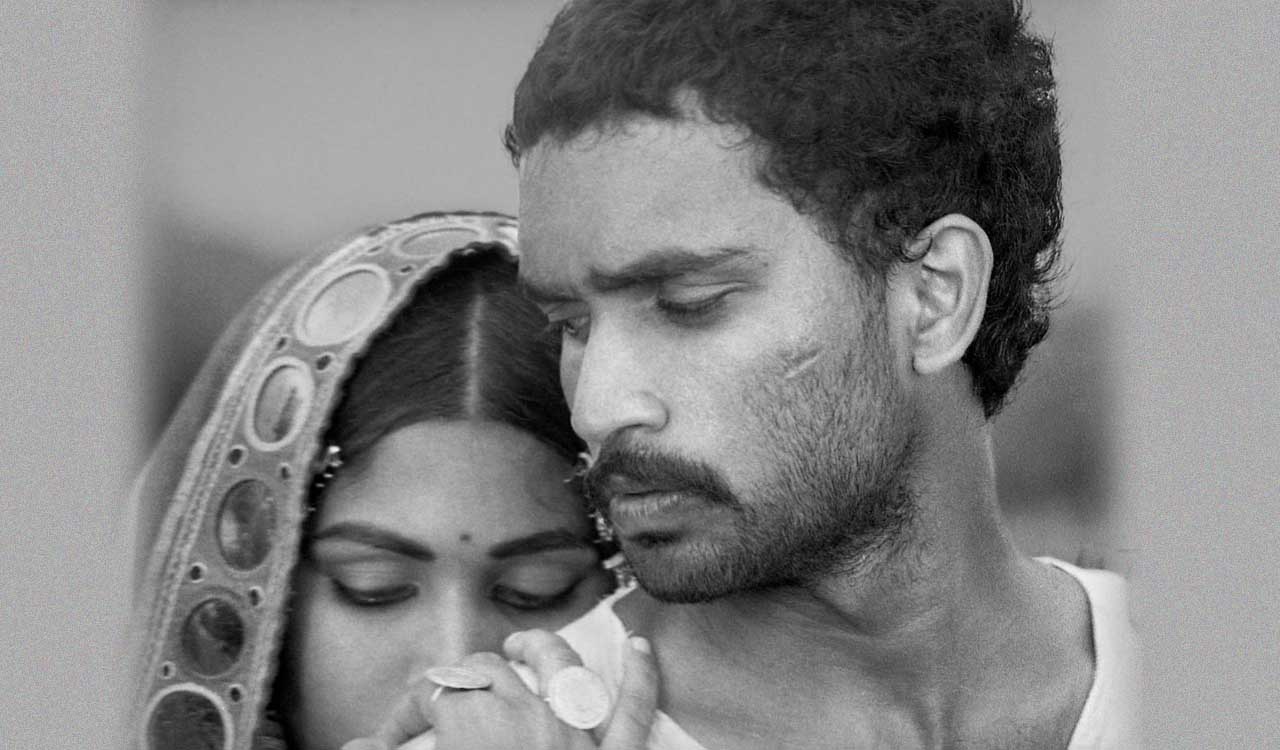

The episodic narrative of the film follows Ramayya from having his first and only shirt torn by the Dora’s henchman just out of spite, to him frolicking around in the village pond while washing the buffaloes, to him growing up to be a young man; all the while continuing to be a labourer. He falls in love with Chandri, a pretty Lambadi woman and they sneak off into the hills for passionate romance and after that is where the story turns around.

Chandri is ordered to sleep with the Dora’s son and her compliance makes Ramayya jealous and he runs away from the village, eventually ending up in Hyderabad where he works as a rickshaw puller and one of his customers is a communist organiser. This man is an allusion to the Marxist writer Makhdoom Mohiuddin. He guides Ramayya to join the rickshaw pullers union, helps him write letters to his father, and that is also when Ramayya first holds a book in his hands. Here, the leftist orientation of the film is emphasised more when he holds the book upside down as he can’t read or write, but when there’s a picture of Karl Marx in the book, he turns it the right side up; symbolically representing that Marxism is the way to turn the society around.

Ramayya also listens to news on the radio around this time and it is then that he is told that what is said on the radio is manipulated information by the government. The movie was made in 1979 and the story is set in the 1940s but even in 2023, the systemic manipulation of media has not gone away, and in fact, is in its extreme form. Other aspects that are still relevant include the imprisonment of political dissenters, nexuses between the establishment and businessmen, and the general sense of fear instilled among the common people.

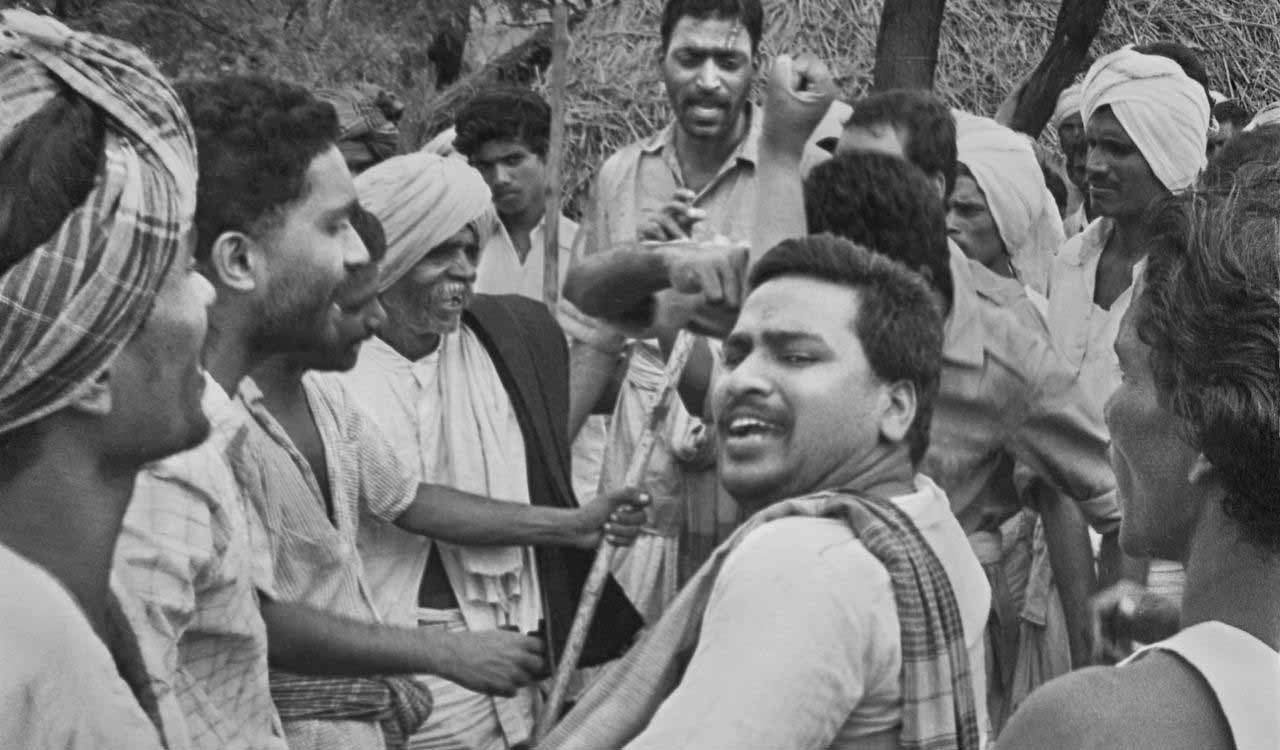

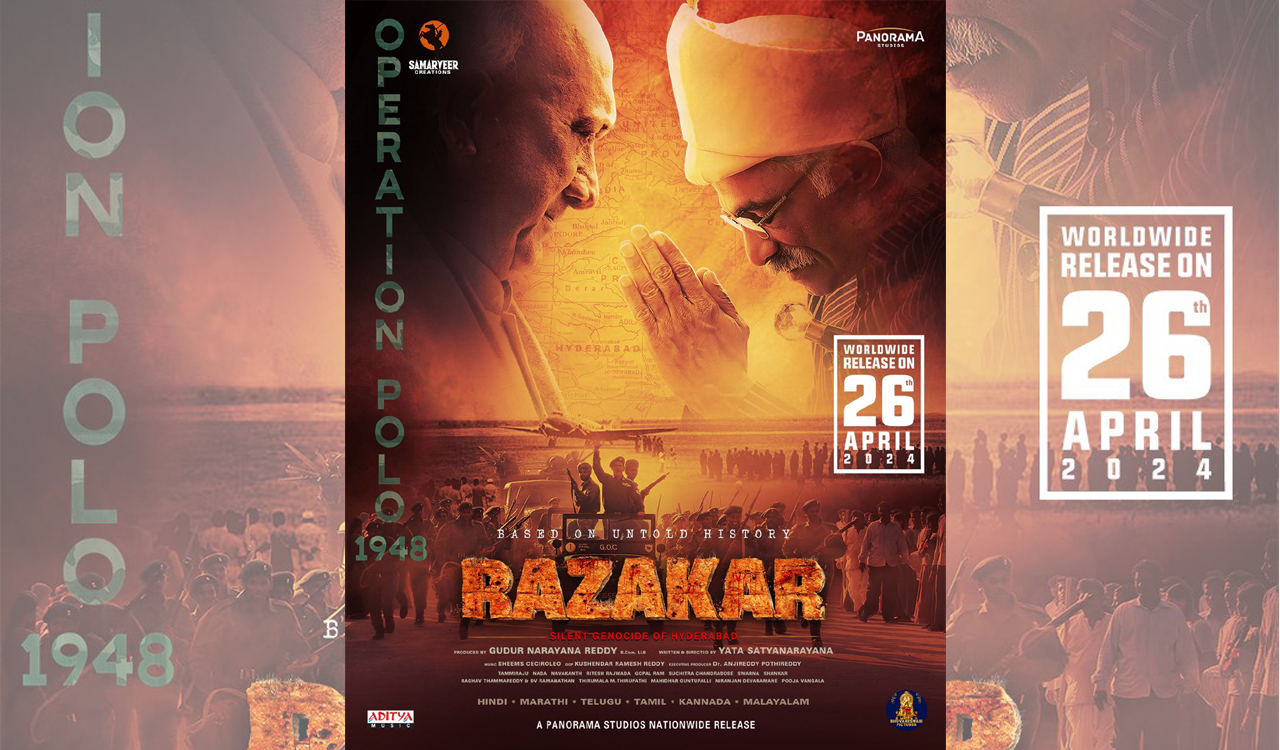

Things peak when Ramayya goes to a village to deliver a letter by the communist leader and sees the violence and the havoc that the Razakars have wreaked on the village. That is when he decides to take up arms and leads a guerilla force against the Dora, making him escape with his life. Ramayya then burns all the land documents and distributes the land among all the peasants. The same is the scene across Telangana, as hundreds pick up weapons and fight the Razakars and the landlords.

The Razakars are supported by the landlords and vice versa, and considering the fact that state-supported vigilantism still goes on unabashedly in parts of the nation, one wonders if anything has changed in the past eight decades.

Meanwhile, India gets independence and the Nizam surrenders to the Indian forces after Operation Polo, and the Hyderabad state is annexed into the union of India. The peasant revolt does not stop and the violence continues, and eventually Ramayya succumbs to police bullets in a fierce firefight.

Post-climax is where the nexus between the businesses/powerful individuals and the establishment is further highlighted when all the Doras speak with government officials, promising them their loyalty, in exchange for retaining their lands and their wealth. This scene is a repeat of an earlier scene where they swear their allegiance to the Nizam. This part of the movie is another still-relevant aspect, as we still hear a lot about powerful people who supported one party earlier and are now hand-in-glove with the ruling parties all over.

The inference here is that nothing has changed except time and technology. Just like the Doras of that age, the modern day Doras, including the rich and the politicians, rule over the lives of crores of people whose only goal in life is to put food on the plate; just as Ramayya’s father tells him early on in the movie “chachettattunna paniki povale” (you have to go to work even if you are about to die).

(This article was authored by Anveshi.)

Related News

-

25th batch of police canines, handlers pass out at IITA Moinabad

37 mins ago -

Kharge slams AI Summit management, alleges global embarrassment

56 mins ago -

PM Modi calls India AI Impact Expo 2026 powerful convergence

1 hour ago -

Writing code will not be main goal in AI era: Infosys Chairman

1 hour ago -

India contributes 16 per cent of world AI talent, white paper reveals

1 hour ago -

Kukatpally family conducts funeral after days of prayers for deceased

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad-based startup to begin human clinical trials for India’s first AI-driven antibiotic

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Mega job fair on February 23 at Red Rose Function Hall

2 hours ago