Opinion: All Muslims are not terrorists. Period

We must confront terrorism firmly, and confront stereotyping just as firmly because when fear replaces facts, everyone is less safe

By T Muralidharan

If you spend time in WhatsApp groups — family groups, housing societies, alumni circles, workplace forums — you will recognise the pattern instantly. A violent incident occurs somewhere in the world. Within hours, forwards begin circulating: a short video clip, a cropped image, a provocative caption. Then comes the leap that is actually a logical blunder: “They were Muslims… therefore Muslims are terrorists.”

Also Read

It sounds decisive. It feels emotionally satisfying. And it is completely wrong.

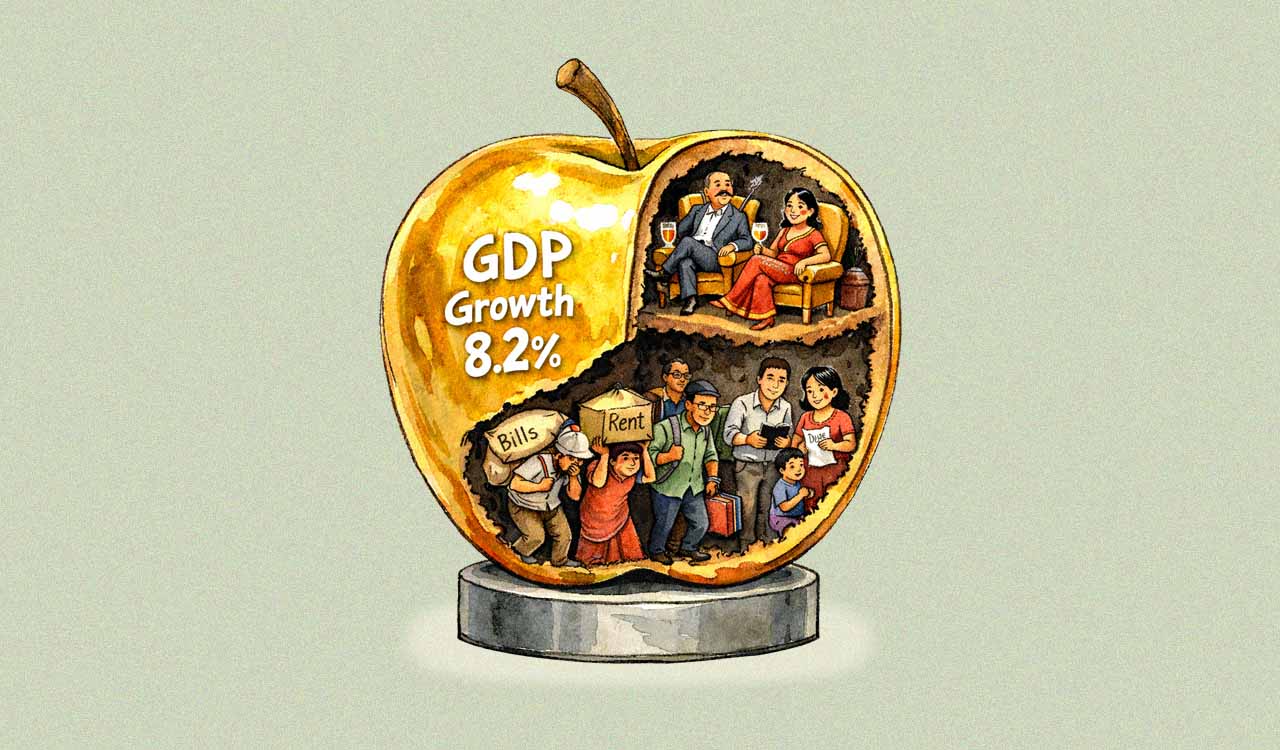

This opinion piece is not about denying terrorism. Terrorism exists, it is brutal, and it must be confronted firmly by the state through intelligence, policing, law and international cooperation. What this piece argues against is something else entirely: the lazy and dangerous habit of converting the crimes of a tiny violent minority into a permanent stain on nearly two billion people, most of whom live ordinary lives as neighbours, colleagues, professionals, farmers, traders, students and citizens — including over two hundred million Indians.

The fallacy hiding in plain sight

The statement “Every terrorist is a Muslim, therefore every Muslim is a terrorist” commits a classic reasoning error known as the converse fallacy, also called “affirming the consequent”. It confuses two very different probabilities: Probability (Muslim | Terrorist) and Probability (Terrorist | Muslim). These two are not interchangeable. Even if a significant share of terrorists identified in news reports belong to one group, it does not follow that members of that group are likely terrorists.

The missing piece of logic is the base rate — the size of the overall population from which the subset comes.

Base Rate Reality

According to long-term demographic research by the Pew Research Center, Muslims today number about two billion people, roughly one quarter of humanity. Against this scale, even exaggerated estimates of violent extremists — running into tens of thousands globally —represent well under 0.001 per cent of Muslims. In probability terms, the chance that a randomly encountered Muslim is a terrorist is so small that it is statistically negligible.

Yet the human mind does not naturally grasp such proportions. It does not intuitively process millions or billions. It works with stories, images, faces and repetition. This mismatch between how reality is structured and how the brain processes information creates fertile ground for generalisation.

Brain’s default setting

Why does our brain generalise before it thinks? Neuroscience offers a sobering explanation. The human brain evolved for speed, not statistical accuracy. It is a pattern-recognition machine designed to quickly detect threats. In evolutionary terms, false alarms were cheaper than missed dangers. Mistaking a stick for a snake causes momentary panic; mistaking a snake for a stick could be fatal.

After the Bondi Beach attack in Sydney, a detail barely travelled on social media: a Muslim fruit seller tackled an armed attacker and disarmed him, an act which saved lives

As a result, the brain tends to overgeneralise danger. Fear and anger activate the amygdala, the brain’s threat centre, while suppressing the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for reasoning, nuance and probability assessment. When emotion rises, analytical thinking falls.

This is why rare but dramatic events feel common, and why group identity replaces individual perpetrator unless we consciously slow down and think. Generalisation is the brain’s default setting. Accuracy requires effort.

Where terrorism actually occurs

Another reality routinely ignored in casual conversations is where terrorism happens. Global studies consistently show that more than 90 per cent of terrorist attacks and nearly all terrorism-related deaths occur in active conflict zones — regions suffering from prolonged war, insurgency, state collapse and weak governance.

Violence thrives where institutions fail. Most ordinary Muslims —especially those living in stable societies like India — have no connection to such violence, just as most Indians have no connection to Maoist insurgency, organised crime or secessionist movements. Context matters. Geography matters. Governance matters.

Manufacture of perception

Public perception does not emerge in a vacuum; it is shaped. Peer-reviewed research in the United States, reported by Reuters, has shown that attacks involving Muslim perpetrators receive 357 per cent, or more than three times, the media coverage of comparable attacks by non-Muslims. This does not require malicious intent to have consequences. Repetition alone is enough.

When one category of violence is repeatedly framed as “terrorism” and replayed endlessly, while other forms are framed as isolated crimes or personal tragedies, the public begins to associate terror with identity rather than with aberrant behaviour. The media does not need to lie to mislead. Selective amplification is sufficient.

WhatsApp: The most efficient amplifier of error

If mainstream media creates the spark, WhatsApp pours the fuel. WhatsApp combines speed without verification, emotion without context, and trust without accountability. Messages arrive not from strangers but from friends, relatives and colleagues. Repetition inside closed groups creates certainty.

Over time, suspicion hardens into common sense. In a country as diverse and interdependent as India, this is not harmless chatter. It corrodes trust at the level where society actually functions —neighbourhoods, workplaces, classrooms and markets.

A real incident that breaks the stereotype

When violent attacks occur and perpetrators claim an Islamic justification, public discussion often stops at identity. But reality is more complex. After the Bondi Beach attack in Sydney this month, international reporting highlighted a detail that barely travelled on social media: a Muslim fruit seller, a civilian, ran towards the gunfire, risking his life, tackled an armed attacker and disarmed him, an act which saved lives.

The attacker’s identity became viral. The rescuer’s identity did not. Stereotypes travel faster than truth because they are simpler.

Who actually pays the price

The greatest victims of this fallacy are not abstract groups; they are ordinary, moderate Muslims, who form the overwhelming majority. They are asked to explain crimes they condemn. They are viewed with suspicion for acts they had nothing to do with. Over time, many retreat from public conversation, leaving the centre empty and allowing extremists of all kinds to dominate narratives.

This is not only morally wrong; it is strategically foolish. Alienating moderates strengthens radicals.

When the same fallacy turns inward

This reasoning error is not confined to Muslims or to India. It is increasingly visible within Western societies themselves, especially in the United States. America experiences tens of thousands of gun deaths every year, most unrelated to terrorism. Yet framing shifts sharply depending on identity.

When attackers are Muslim, the word ‘terrorism’ appears instantly. When attackers are native-born or politically radicalised online, narratives often pivot to mental health, loneliness or grievance. In recent years, the term domestic terrorist has entered political rhetoric more aggressively. Critics argue it is sometimes used loosely, turning ideology into suspicion.

The same fallacy reappears: individual violence, broad ideological label, collective suspicion. Today, even being liberal or conservative can be treated by some as a warning sign. The target changes. The logic does not.

Why this matters for India

India is not a society that can afford lazy thinking. Our diversity is not decorative; it is structural. Millions depend daily on trust across religious, linguistic and regional lines.

When statistical ignorance masquerades as wisdom, we weaken that trust. We distract ourselves from real challenges — jobs, education, public safety and governance — and hand extremists exactly what they want: fear, division and attention.

The bottom line

“All Muslims are not terrorists — for God’s sake” is not an emotional slogan. It is a demand for basic intellectual discipline. A subset is not an identity. A headline is not a dataset. A WhatsApp forward is not proof.

We must confront terrorism firmly. And we must confront stereotyping just as firmly. Because when fear replaces facts, everyone becomes less safe — and the most decent among us, the moderates, pay the highest price.

(The author is an independent journalist)

Related News

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

7 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

7 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

7 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

7 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

8 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

8 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

8 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

8 hours ago