Opinion: BC reservations must follow law, not political urgency

Justice for BCs demands more than declarations. It demands law, data, transparency, and public confidence

By Dr Vakulabharanam Krishna Mohan Rao

In a constitutional democracy, noble intentions are not enough. Every measure, especially those that claim to serve social justice, must be rooted in lawful authority, legislative procedure, and democratic transparency.

Also Read

The Telangana government’s recent ordinance to implement 42 per cent reservations for Backward Classes (BCs) in Panchayati Raj institutions, though seemingly pro-BC, bypasses critical constitutional steps. This undermines the very objective it claims to uphold. If justice for BCs is the true intent, then the path must be lawful, data-driven, and institutionally anchored.

The Ignored Lawful Path

On March 17, 2025, the Telangana Legislature unanimously passed two Bills proposing 42 per cent BC reservations in local bodies, education, and public employment. These were sent to the President for assent under Article 200 and Article 31C of the Constitution. However, before receiving presidential assent, the State government prorogued the Houses and took the ordinance route to push the same issue. This move raises serious constitutional questions.

SEEEPC survey was neither supervised by the BC Commission nor by any autonomous statutory body and, hence, cannot serve as the legal bedrock for a reservation policy likely to face judicial scrutiny

Once the Governor reserves the Bills for the President, issuing an ordinance on the same subject undermines the doctrine of pith and substance. Legal experts argue this may violate federal comity and invite judicial intervention. The President has not yet granted assent.

In fact, a recent Supreme Court judgment — interpreting a reference made under Article 143(1) (Presidential Reference) — emphasised that State Bills sent to the President require detailed scrutiny, especially if they touch upon constitutional amendments, reservation ceilings, or federal balance.

In this context, expeditious presidential assent cannot be presumed. Any legislative detour through an ordinance only adds to the uncertainty and invites litigation.

Flawed Data Foundation

At the core of the 42 per cent reservation proposal lies the SEEEPC survey (Social, Educational, Economic, and Employment Profile of Communities), conducted by the Planning Department. However, this survey:

- Was not conducted under Article 340 of the Constitution

- Was not notified under the Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952

- Was not covered under the Collection of Statistics Act, 2008

- Had no Gazette notification, no independent oversight, and no public consultation

In short, the SEEEPC survey lacks legal standing. It was neither supervised by the BC Commission nor by any autonomous statutory body. Its findings, therefore, cannot serve as the legal bedrock for a reservation policy likely to face judicial scrutiny.

Justice Sudarshan Reddy Working Group — Still Not Statutory

To analyse the SEEEPC data, the government formed an Independent Ex-pert Working Group under retired Supreme Court judge Justice Sudarshan Reddy, comprising eminent names such as Thomas Piketty, Jean Drèze, Prof Kanche Ilaiah, and others. However, this group:

- Was not a statutory commission

- Had no Gazette Notification

- Had no clearly published Terms of Reference

- Did not involve any legislative discussion or public debate

Though it claimed the SEEEPC survey was “scientific” and “a model for the nation,” these opinions, however prestigious, cannot replace the requirement of a law-backed commission. The Vikas Kishanrao Gawali judgment (2021) explicitly stated that data used for BC reservations must emanate from a duly constituted statutory commission. The Justice Reddy group was only a government-appointed panel — not legally empowered to anchor reservation policy.

Busani Commission: Another Inadequate Attempt

Before the ordinance, the government had relied on the Busani Commission, believing it could fulfil the “dedicated commission” requirement of the triple test. But the commission suffered from fatal flaws:

- It was not constituted under Article 340

- It had no Gazette Notification

- It lacked public Terms of Reference

- It did not conduct independent field studies

- It relied solely on SEEEPC data, which is itself non-statutory

- Critically, it submitted its report only for rural local bodies, leaving urban and municipal bodies unaddressed

- Its report was not tabled in the Legislature and no public consultation was undertaken

Thus, the Busani Commission failed to meet both procedural and legal standards. In effect, it cannot be treated as a valid, independent, or comprehensive source of evidence for reservation justification.

Supreme Court Doctrine: Triple Test and Legal Benchmarks

The Supreme Court has consistently clarified the conditions for local body reservations in key judgments:

- Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) : BC reservations must be based on empirical data produced by a competent expert body

- K Krishna Murthy v. Union of India (2010) — Introduced the Triple Test: A dedicated commission must conduct a contemporaneous study; Reservations must be justified by empirical data; they must not breach the 50 per cent cap, unless extraordinary circumstances are shown

- Vikas Kishanrao Gawali v. State of Maharashtra (2021): Maharashtra’s BC reservations in Beed district were struck down due to failure to comply with the triple test; the Court emphasised that data alone is insufficient — it must be produced by a statutory commission with legislative scrutiny

Together, these rulings form a clear constitutional pathway: procedural compliance, data legitimacy, and institutional credibility are non-negotiable.

The Piketty Controversy and Public Distrust

The inclusion of internationally reputed economists such as Thomas Piketty triggered public debate. Many questioned why local social scientists, with a deeper understanding of caste and community in Telangana, were excluded from the Working Group. The government’s silence on this matter and its failure to clarify the legal validity of the group further eroded public trust. Even the most esteemed academic opinions cannot substitute legal compliance. In constitutional policymaking, transparency, process, and public accountability are essential.

Ordinance Is Temporary — Not a Constitutional Shortcut

Article 213 empowers the Governor to promulgate ordinances only when the legislature is not in session and an urgency exists. But this cannot be a substitute for normal legislative functioning. As per Article 213(2)(a), any ordinance must be laid before the Legislature within six weeks of reassembly and converted into an Act. Otherwise, it automatically lapses.

In Telangana’s case, the ruling party enjoys a legislative majority. There was no constitutional necessity to bypass normal legislative channels. The suspicion that this ordinance was hurriedly brought in to meet the High Court’s September 30 deadline for local body elections is hard to ignore.

However, courts have made it clear: urgency does not validate illegality. Even with noble intentions, reservation ordinances that are not based on valid data, lawful procedure, and inclusive institutional backing are prone to be struck down by constitutional courts.

The Way Forward: Anchoring in Law and Legitimacy

Reservation for BCs is a constitutional responsibility, not a political expedient. Any lasting policy must:

- Be based on a survey conducted by a statutory, independent commission

- Involve the State BC Commission formally

- Ensure public consultation, legislative debate, and transparency

- Be passed by the Legislature and receive presidential assent

Empty symbolism or rushed processes cannot withstand judicial review. As the Supreme Court has reiterated, constitutional validity flows from law — not sentiment.

The Telangana government must re-evaluate its approach to BC reservations. The ordinance path is not only legally vulnerable but also procedurally flawed. Justice for BCs demands more than declarations. It demands law, data, transparency, and public confidence. Let us not dilute constitutional values in the name of urgency. Let us reaffirm them through compliance. Only such efforts will sustain BC reservations and uplift backward communities within the framework of our democracy.

(The author is former Chairman, Telangana State Backward Classes Commission)

Related News

-

Telangana sets up Rythu Discom, liabilities of Rs 71,964 crore shifted

-

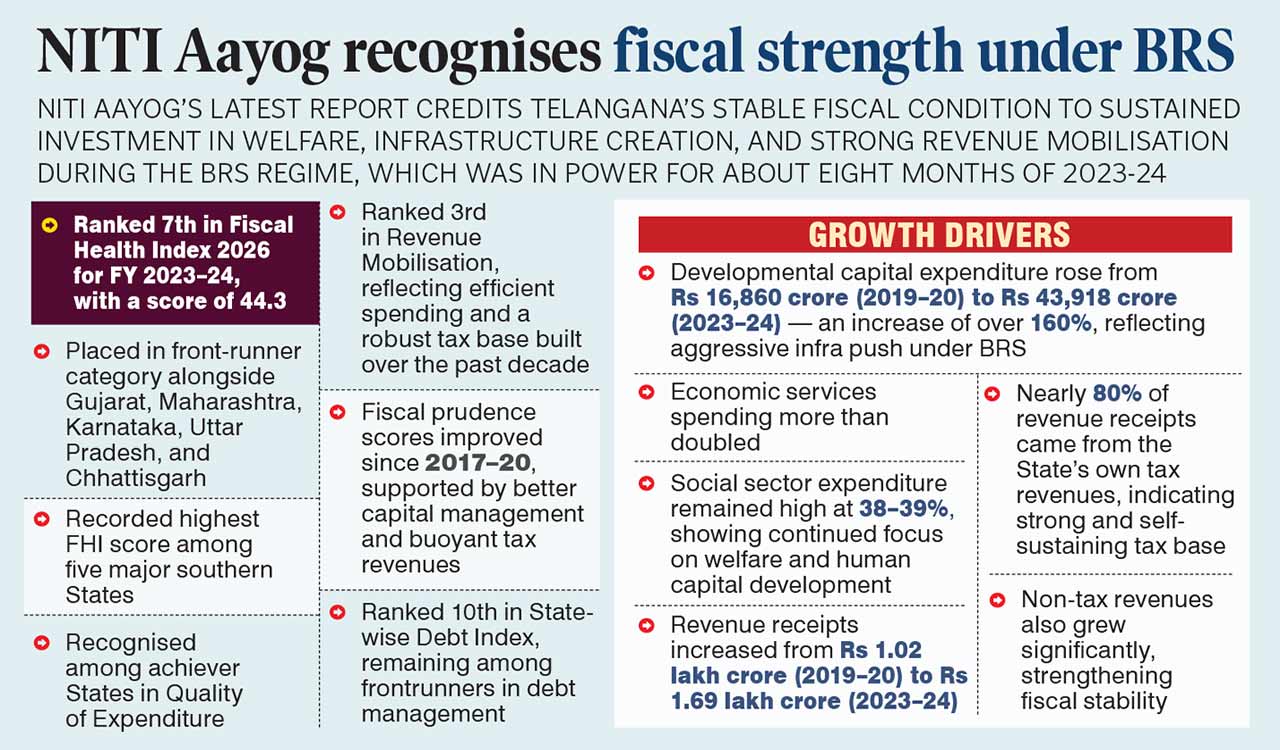

Telangana ranks 7th in NITI’s Fiscal Health Index for 2023-24, reflects BRS’ strong policies

-

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

Hyderabad cybercrime cracks down on 124 social media accounts promoting online betting

-

Iran allows India-flagged tankers through Hormuz after talks between EAM Jaishankar, Araghchi

7 mins ago -

Jammu: Gunfire at event attended by NC chief Farooq Abdullah, suspect held

18 mins ago -

Terrorist hideout busted in J&K’s Rajouri; IED recovered

27 mins ago -

Blaze rips through Delhi’s Matiala slum cluster; no casualties

34 mins ago -

Damage to historical sites in Iran raises alarm about war’s impact on protected places

43 mins ago -

NIA raids underway in terror conspiracy case in J&K’s Poonch

58 mins ago -

Sensex, Nifty fall over 1 pc as Brent Crude crosses $100

1 hour ago -

Cartoon Today on March 12, 2026

1 hour ago