Opinion: Bihar’s failed war on alcohol, and its human cost

Over 13 lakh arrests, just 1% convictions, and rising corruption — a policy meant to curb drinking has ended up punishing the poor

By Ghanshyam Sharma

Over the past two decades, Bihar has conducted a unique experiment in alcohol regulation. Starting in 2006, it actively promoted the sale of alcohol. However, in 2016, it reversed course and introduced one of the strictest alcohol bans in the country.

Also Read

In High Spirits

After the 2005 elections, the Bihar government promoted the sale of alcohol to boost tax revenues. It pursued a policy to open a theka (liquor shop) in every panchayat. Media reports noted that the number of liquor shops in rural areas tripled, from 779 to 2,360. As a result, tax revenues from alcohol jumped from Rs 87 crore to Rs 3,142 crore in 2014-15, accounting for 15 per cent of the State’s budget.

Due to increased proximity to liquor shops, the percentage of men with alcohol addiction (those who drink daily or weekly) increased by 50 per cent (NFHS-3 and 4). People often develop an addiction to alcohol due to physical or emotional dependence on alcohol. For example, manual labourers drink alcohol to deal with chronic pain, especially in the absence of reliable and accessible healthcare.

Similarly, people who have been exposed to childhood adversity or are dealing with mental health issues are more likely to turn to alcohol for relief. When access to alcohol improves, such people are likely to increase their frequency and volume of consumption. Thus, the policy exploited the vulnerable groups prone to alcohol addiction to raise tax revenue.

However, the overall percentage of men in Bihar who drink alcohol actually declined during this period, despite the government’s efforts to promote it. The proportion of married women who reported that their husbands drank alcohol fell from 39 to 35 per cent (National Family Health Survey-3 & 4).

Imposing Ban

In 2016, Bihar flipped and imposed a comprehensive ban on alcohol with draconian penal provisions. For example, the provision of ‘guilty until proven innocent’ placed the burden of proof on the accused. According to the Transparency International Report (2019), Bihar is the most corrupt State in India. This law made citizens vulnerable by vesting indiscriminate powers with the police to arrest people without proof. The law also prescribed life imprisonment for drinking in a public place and up to eight years’ imprisonment for merely possessing knowledge about alcohol. Such rigorous penal provisions came as a shock, especially since alcohol use was already declining in the State.

Predictable Consequences

The law has had several predictable consequences. Since 2016, Bihar has arrested over 13 lakh people (mostly men) under the prohibition law, as only half a percent of women drink alcohol in the State (NFHS). The actual conviction rate in these cases is one per cent, according to media reports. Kumar and Raghavan (2020) found that the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) faced disproportionate arrests under this law, and many have been awaiting trial for several years. Over 8 lakh prohibition-related cases have clogged the courts and overcrowded prisons. The prohibition has led to thousands of undocumented deaths from spurious alcohol.

Despite years of strict enforcement, liquor continues to flow through bootlegging and spurious brews, raising questions about the effectiveness and fairness of the State’s prohibition policy

In April 2023, the Supreme Court raised concerns about the fairness of making alcohol consumption a non-bailable offence. The court also questioned whether the prohibition had been effective in curbing alcohol consumption. A recent study published in the journal Economics of Governance reveals that despite such rigorous provisions, there has been only a six percentage point decline among men who drink alcohol. The study also found empirical evidence of bootlegging. Alcohol consumption has declined less in districts that share a border with other States or Nepal. Selling alcohol in districts that do not share a border with other States would imply dealing with two police departments, increasing both the price and risk of sale selling alcohol in such districts.

Further evidence of bootlegging emerges from the sharper decline in low alcohol (eg, beer) drinkers compared to high alcohol (eg, whiskey) drinkers. This is because high-alcohol spirits are easier to store and last longer, whereas low-alcohol drinks may need cold storage. A decline in branded alcohol drinkers was also noticed, but not in spurious liquor consumers. This could be because branded alcohol is imported from outside the State, while spurious liquor can be sourced locally. Branded alcohol is relatively less harmful than locally made liquor, which can be toxic.

It is also worth noting that the prohibition has only deterred occasional drinkers — people whose frequency of alcohol consumption is less than weekly. The ban has not deterred people who drink daily. There is only a two per cent decline in men who drink alcohol daily. This again highlights the wide availability of alcohol and the limitation of the policy.

Globally, governments have realised that educating people is more effective than imposing bans. For example, the US government had to reverse its alcohol ban in the 1930s. Several US states have recently amended their “War on Drugs” policy and legalised certain substances. Prohibitions only lead to black markets, unfair arrests, targeting of vulnerable groups, an increase in corruption, loss of tax revenues, and strengthening of criminal gangs and mafia.

(The author is Associate Professor of Economics, RV University, Bengaluru)

Related News

-

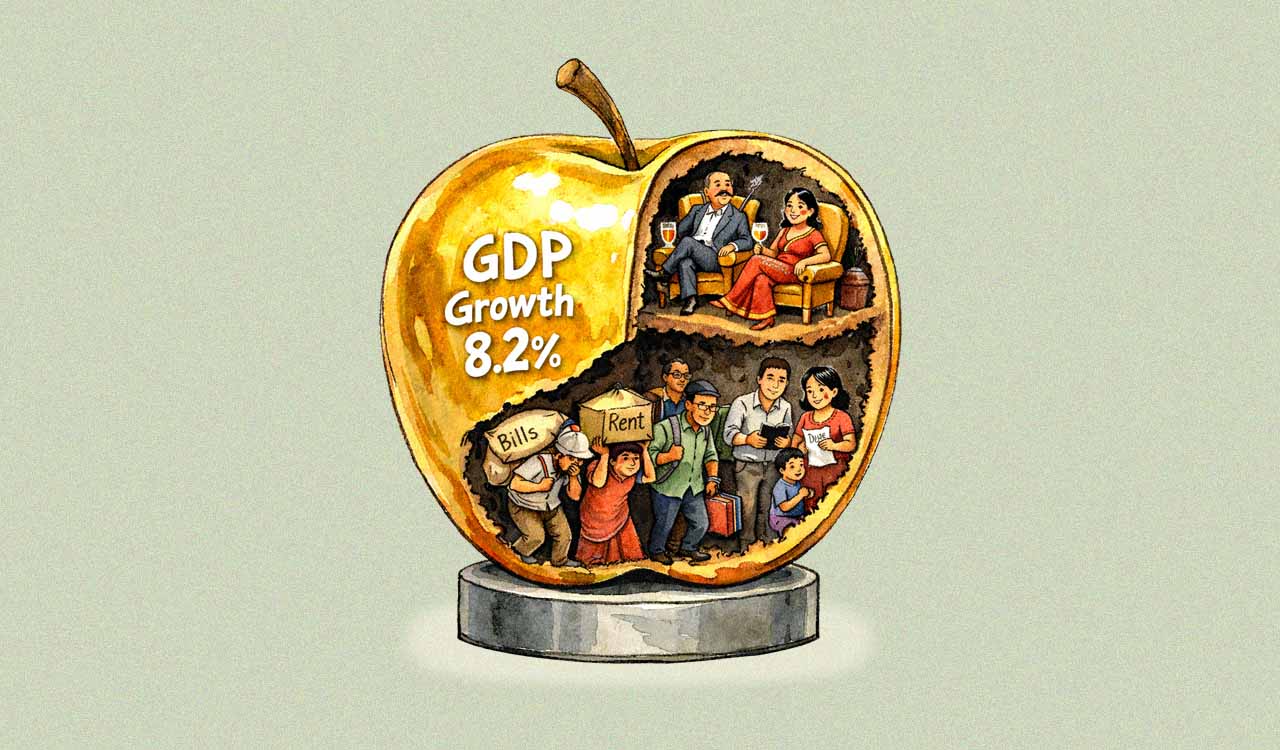

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Cartoon Today on March 11, 2026

13 mins ago -

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

9 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

9 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

9 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

9 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

10 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

10 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

10 hours ago