Opinion: Boredom is good

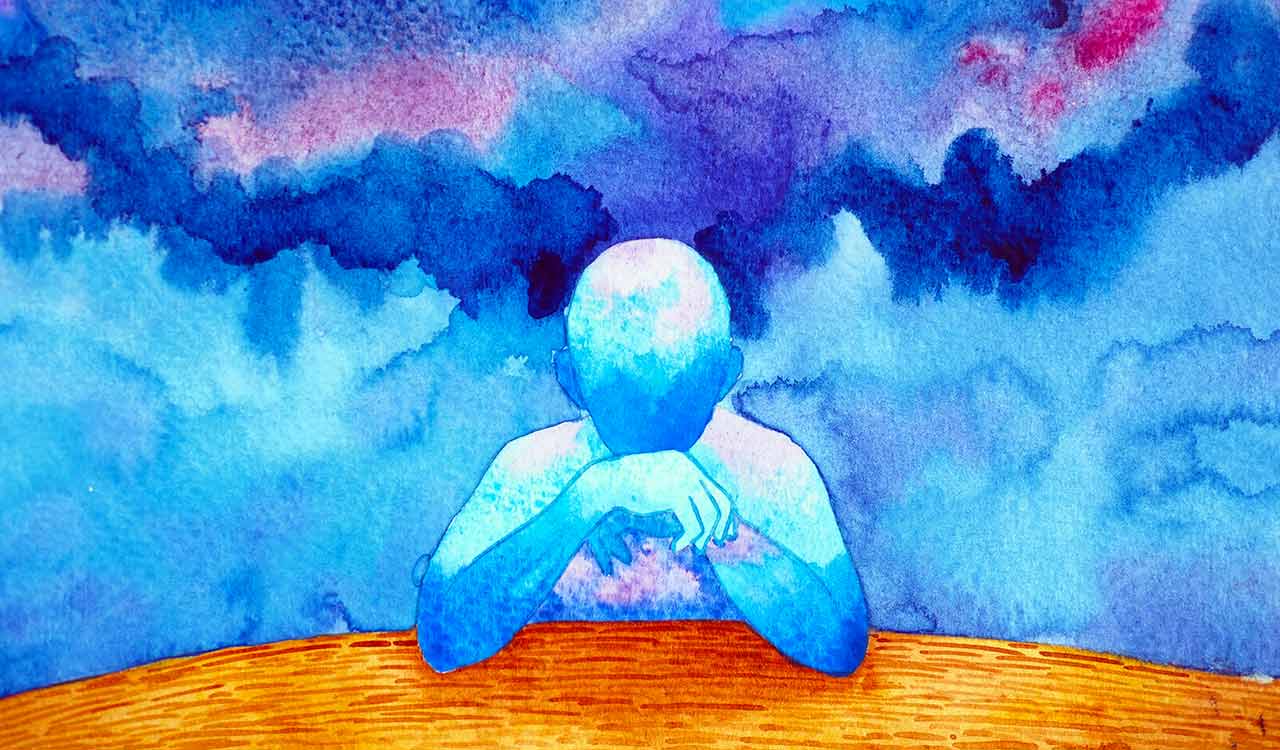

In a world shouting for our attention, boredom is resistance. It is a quiet rebellion against the tyranny of productivity

By Viiveck Verma

At the height of our hyper-connected, productivity-obsessed culture, boredom has become almost taboo. We recoil from it like a virus, swiping, scrolling, and scheduling every last idle minute. Apps are designed to capture our attention within milliseconds. Notifications ping before our thoughts can meander. We are a society allergic to stillness. And yet, as someone who has spent decades studying and participating in creative industries, I’m convinced of one thing: boredom is not the enemy. It is, in fact, an essential ingredient of creativity. Doing nothing—true, honest-to-God nothing—is a creative act in itself. This is not a romantic notion. It is a neurologically, psychologically, and historically grounded one.

Eureka Moments

When our minds are unoccupied, they begin to wander. Neuroscientists refer to this as the ‘default mode network’, a network of brain regions that activates when we are not focused on the outside world. In these moments of apparent rest, the brain is busily engaged in internal tasks like mental time travel, autobiographical memory, envisioning the future, and crucially, making connections between disparate ideas. It’s precisely this kind of background cognitive process that underlies much of creative thinking.

For much of history, doing nothing was an acceptable, even noble, pursuit. Philosophers from Socrates to Heidegger have extolled the value of contemplation

In other words, creativity is not born in the white-hot rush of input, but in the slow burn of introspection. Einstein reportedly claimed his best ideas came to him while shaving. JK Rowling conceived the idea for Harry Potter while delayed on a train, staring out the window. Archimedes had his famed Eureka moment in the bath. What unites all these origin stories? Not hard work in the conventional sense, but open time. Mental loitering. Boredom.

Yet in our culture, boredom is pathologised. Even children are no longer allowed to be bored—every moment must be optimised with apps, classes, and enrichment activities. We do not let minds meander; we march them forward in lockstep with optimisation. We demand output at the cost of insight. It wasn’t always this way. For much of history, doing nothing was an acceptable, even noble, pursuit. Philosophers from Socrates to Heidegger have extolled the value of contemplation. In the East, traditions like Zen Buddhism explicitly emphasise the power of stillness, of attention to the breath and the moment. Poets, painters, and inventors across centuries understood the need for long periods of apparent unproductivity. The muse, they knew, does not arrive on a schedule. She shows up in moments when we have finally put our devices down and surrendered to the empty page.

Creative Breakthroughs

Modern research supports what ancient wisdom intuited. A 2014 study from the University of Central Lancashire found that participants, who first performed a boring task, copying phone numbers from a directory, produced more creative ideas on a subsequent test than those who hadn’t. The boredom primed their brains for lateral thinking. Another study from the University of York and the University of Florida revealed that daydreaming during idle moments improved problem-solving abilities. It appears that cognitive drift, the very thing boredom induces, is not a bug but a feature. Still, we resist. We lionise the hustle and demonise the pause.

Silicon Valley CEOs boast of 4 am wake-ups and 18-hour workdays. Social media amplifies productivity literature, like bullet journals, hustle memes, and desk setups optimised for ‘flow’. We conflate motion with meaning, and I find this deeply misguided. Creative breakthroughs are not built on constant action. They are built on the soil of stillness. I have seen this time and again, not only in artists and writers but in engineers, architects, and even surgeons. The most generative minds are those that can endure silence. Those who do not panic when faced with the empty space of thought.

The Unstructured

To be clear, this is not a case for laziness. There is a difference between intentional idleness and passive consumption. Boredom is not scrolling Instagram while watching Netflix. It is not simply being unoccupied; it is being open to the unstructured. Boredom, in its purest form, is spacious attention. It allows the self to re-emerge without external interference. The trouble is, boredom feels uncomfortable. It brings us face-to-face with our own minds, unmediated, uncurated, and unflattering. It is easier to swipe than to confront the silence. But this is precisely why we must defend it. Imagine what we might recover if we allowed ourselves this space. New ideas, yes, but also new relationships with time and self. We might remember what it means to feel wonder at the wind in the trees, to follow a half-formed thought like a string, to stare at the ceiling and actually notice what arises. In a world shouting for our attention, boredom is resistance. It is a quiet rebellion against the tyranny of productivity.

So I propose we reclaim boredom. Not as a failure of imagination but as its fertile ground. Let your children get bored. Let your meetings end early. Take a walk without your phone. Protect the interstices of your day. Because in those overlooked moments, in line at the bank, on the commute home, in the quiet hour before dinner, there lies the possibility of creativity not yet named.

(The author is founder and CEO, Upsurge Global, co-founder, Global Carbon Warriors and Adjunct Professor, EThames College)

Related News

-

Dube, Chakravarthy power India to win over Netherlands

2 mins ago -

Praful Patel backs demand for CBI probe into Ajit Pawar plane crash

15 mins ago -

Editorial: India-France tango uplifts the mood

41 mins ago -

D K Shivakumar tells Karnataka contractors govt will pay as per budget

57 mins ago -

Is it a crime to win majority of wards, Suman asks Vivek before arrest

1 hour ago -

Deer killed in road accident in Kothagudem

2 hours ago -

Speaker concludes hearing on disqualification petition against Danam Nagender

2 hours ago -

Consumers’ body wants BIS Standards Clubs set up in schools, colleges in Telangana

2 hours ago