Opinion: Caste and Cash, the persistent shadow on India’s ballot

As Telangana votes, let it serve as a reminder that democracy thrives not on caste or cash, but on informed choice and accountability

By Chittarvu Raghu

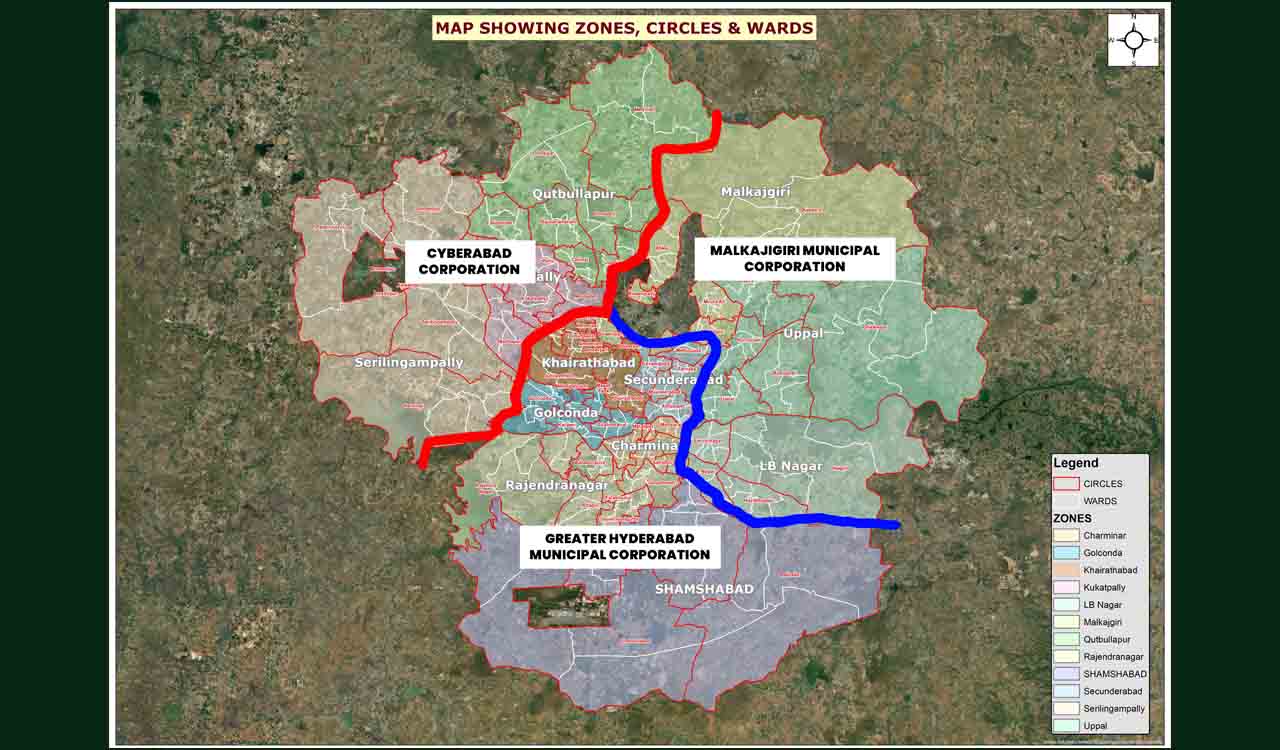

As Telangana gears up for panchayat elections, with polling scheduled in multiple phases starting from October, the spotlight once again falls on the entrenched roles of caste and cash in shaping electoral outcomes. This local body poll, involving over 1.67 crore voters and featuring a newly extended 42 per cent reservation for Backward Classes (BCs), underscores how identity politics and financial inducements continue to distort the democratic process. In a nation that prides itself on being the world’s largest democracy, these elements represent a regressive force, compelling us to question whether true electoral reform is feasible amid deeply rooted social and economic structures.

Also Read

India’s democratic journey began on a foundation of high ideals. Post-Independence, with literacy rates hovering below 20 per cent, elections were fought on grand narratives of nation-building, economic self-reliance, and social equity, championed by leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and BR Ambedkar. Voters, despite limited education, engaged with these principles, drawn from the ethos of the freedom struggle. However, this ideological fervour has waned over decades, giving way to fragmented, localised contests.

Pivotal Changes

The shift can be traced to several pivotal changes. The political instability of the 1970s, marked by the Emergency and the rise of regional parties, fragmented national platforms into coalitions driven by expediency rather than vision. More profoundly, the economic liberalisation of the 1990s unleashed market forces that amplified the influence of wealth in public life. As state socialism receded, identity-based mobilisation filled the void, with caste emerging as a primary axis of political organisation.

Today, even as literacy rates exceed 77 per cent and the economy surges forward, democratic accountability lags. Parties, sensing the diminishing appeal of broad ideologies, have pivoted to the “caste-cash nexus”—a symbiotic relationship where social identities secure voter bases, and money ensures their loyalty.

This nexus operates as a vicious cycle, eroding the essence of representative democracy. Political parties meticulously calibrate candidate selections to align with dominant castes in constituencies, transforming elections into battles for community supremacy rather than policy debates.

In Uttar Pradesh, for instance, recent elections have seen intensified mobilisation of Dalits and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), often through targeted welfare schemes and alliances, highlighting how caste influences governance at the grassroots. Similarly, in Bihar and other northern states, caste arithmetic dictates alliances, with parties like the Rashtriya Janata Dal leveraging Yadav and Muslim votes to counter upper-caste dominance.

Financial Ventures

Cash amplifies this dynamic, turning elections into high-stakes financial ventures. Beyond legitimate expenses like rallies and advertising, funds flow into direct voter inducements—cash-for-votes schemes that are rampant in rural and local polls.

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections witnessed record seizures by the Election Commission of India (ECI), totaling over Rs 10,000 crore in cash, drugs, liquor, and other inducements—a stark indicator of the scale of illicit financing. Drugs alone accounted for nearly 45 per cent of these seizures, pointing to a nexus between narcotics trafficking and electoral funding. In the Delhi Assembly elections of 2025, seizures of liquor and cash surged compared to 2020, with increased arrests underscoring the persistent challenge.

Despite court rulings, ECI reforms, and rising literacy, India’s elections remain clouded by identity politics and illicit campaign financing, eroding democratic fairness

Parties increasingly nominate affluent candidates—business tycoons or self-financed individuals—who bear the brunt of campaign costs, including unaccounted expenditures. This privatisation of electoral funding shields party coffers from scrutiny while perpetuating inequality. In Telangana’s upcoming panchayat polls, reports suggest that cash flows are already influencing candidate selections in mandals with strong BC representation, where the new quota has heightened caste-based competition.

Gatekeepers of Ethics

The onus for reform lies squarely with political parties, which must prioritise democratic integrity over short-term gains. In a parliamentary system, parties are the gatekeepers of electoral ethics, yet they often exploit loopholes in statutes like the Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951. The RPA’s expenditure caps—Rs 95 lakh for Lok Sabha seats and Rs 40 lakh for Assembly constituencies—are unrealistically low, compelling candidates to rely on black money. Enforcement remains weak, with the ECI hampered by limited resources for monitoring grassroots transactions.

Recent ECI initiatives offer glimmers of hope. In the past six months, the Commission has rolled out 28 measures to enhance transparency, including the ECINET portal for streamlined operations and voter list purification in Bihar after 22 years—a reform set to go national. For the Bihar Assembly polls, 17 new initiatives aim to curb inducements and boost inclusivity. Experts, including associations like the Association for Democratic Reforms, advocate for ceilings on party expenses, simultaneous elections, and stricter disclosure norms to level the playing field.

The judiciary has played a pivotal role in addressing financial opacity. In February 2024, a unanimous Supreme Court verdict struck down the Electoral Bonds Scheme, deeming it unconstitutional for violating voters’ right to information under Article 19(1)(a). The court highlighted how anonymity fostered quid pro quo arrangements, where corporate donors could influence policy in exchange for contributions. It also invalidated unlimited corporate donations, labeling them arbitrary and prone to corruption.

Post-verdict, transparency advocates hailed it as a win for democracy, though curiously, over 8,000 bonds were printed afterward at public expense, raising questions about implementation. The ruling’s impact was felt in the 2024 elections, where opposition parties leveraged it to critique the BJP’s funding dominance, yet the scheme’s legacy lingers in opaque high-level financing.

Despite these strides, caste and cash remain woven into India’s electoral tapestry, especially at local levels like Telangana’s panchayats. The government’s 2025 decision to include caste in the national census—the first comprehensive count since 1931—could provide data for equitable policies but risks entrenching divisions further if politicised. Uttar Pradesh’s recent ban on caste-based rallies signals a pushback, but enforcement will test its efficacy.

True reform demands multifaceted action: parties must foster internal democracy and ethical fundraising; laws should impose realistic caps with robust oversight; and voters must transcend caste loyalties and reject inducements. The ECI’s ongoing efforts, coupled with judicial vigilance, provide a blueprint. Yet, without collective will—from politicians to the electorate—India’s democracy risks remaining compromised, a shadow of its founding promise. As Telangana votes, let it serve as a reminder: democracy thrives not on caste or cash, but on informed choice and accountability.

(The author is a senior Advocate)

Related News

-

Congress leader moves SEC against party MLA over poll malpractice

6 hours ago -

BRS seeks action against Jagga Reddy, flags counting day threat

6 hours ago -

High voter turnout recorded across 19 municipalities in erstwhile Medak district

7 hours ago -

Salman’s brother-in-law gets threat email; Bishnoi gang link suspected

7 hours ago -

BRS slams police inaction over alleged attack by Jagga Reddy

7 hours ago -

Candidate distributes fake gold coins to lure voters in Sircilla

7 hours ago -

Jagga Reddy blames SEC for Sangareddy polling incident

7 hours ago -

India prepare for Pakistan showdown after Namibia game

7 hours ago