Opinion: After Bihar, Assam’s voter list purge — A dangerous precedent for democracy

By tying voter rights to eviction, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma is casting doubt on the legitimacy of citizens who have already navigated the arduous NRC process

By Geetartha Pathak

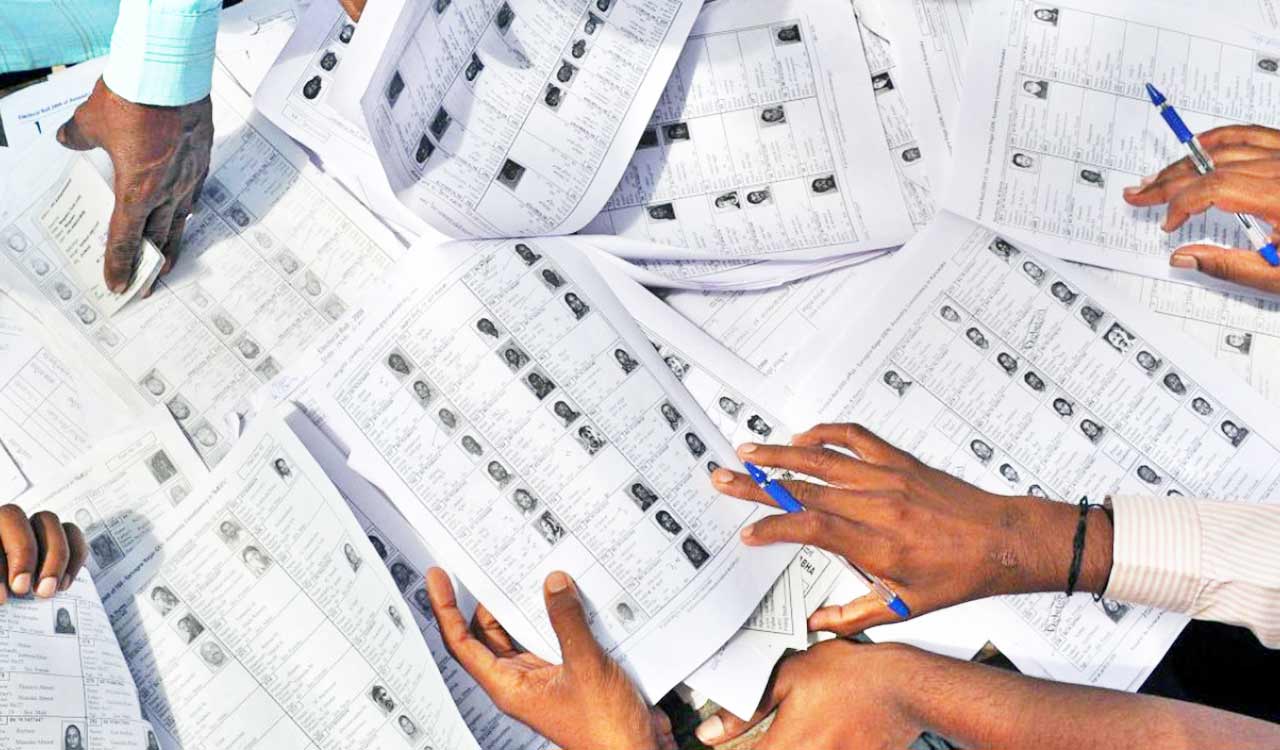

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma recently declared that individuals evicted from encroached government lands would have their names struck off the voter lists of the areas where they were residing illegally. This has sparked intense debate, raising critical questions about the intersection of land rights, citizenship, and democratic participation in the country. Sarma’s move, framed as a measure to protect Assam’s indigenous communities and curb alleged demographic changes, appears to disproportionately target Bengali-speaking Muslims, often vilified as “infiltrators” or “Bangladeshi immigrants.”

This approach not only risks disenfranchising vulnerable populations but also sets a troubling precedent for the erosion of constitutional rights under the guise of administrative action. After the large-scale deletion of names from voters’ lists in Bihar in the name of the Special Intensive Revision, BJP-ruled Assam has devised this new strategy which appears to be aimed at Muslims of the State. These moves indicate that the BJP and its allies fear facing fair democratic contests. Hence, they are resorting to voter disenfranchisement of communities unlikely to support them.

Complex History

Assam has a complex history of demographic tensions, fuelled by decades of migration, both historical and contemporary, particularly from Bangladesh. The State’s politics have long been shaped by anxieties over land, identity, and resources, with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) intensifying these debates. Since assuming office in May 2021, Sarma has overseen aggressive eviction drives, clearing approximately 1,19,548 bighas (160 sq km) of land and affecting around 50,000 people by July 2025. These drives, often justified as reclaiming government or forest land, have predominantly impacted Muslim communities, particularly those of Bengali origin, who are frequently labeled as illegal settlers.

The Assam Chief Minister’s rhetoric, including references to “land jihad” and an “invasion” by people of “one religion,” has added a communal dimension to these evictions. His latest policy of linking eviction to voter list deletion escalates this agenda, framing land encroachment not merely as a legal violation but as a threat to Assam’s cultural and political fabric. By targeting Upper and Northern Assam, where he claims “infiltrators” are now encroaching, Sarma positions himself as a defender of indigenous rights, a narrative that resonates with certain Assamese communities but alienates others.

Right to Vote

The right to vote is a cornerstone of India’s democratic framework, enshrined in Article 326 of the Constitution, which guarantees universal adult suffrage for citizens above 18. While the Election Commission of India (ECI) oversees voter list management, including the removal of names during periodic revisions, such actions must adhere to strict legal guidelines. Names can be deleted if a person is deceased, no longer resides in the constituency, or is disqualified (eg, declared a non-citizen by a Foreigners Tribunal). However, eviction from land, even if deemed illegal, does not automatically strip someone of citizenship or voting rights.

Former Chief Election Commissioner Ashok Lavasa has stated that “eviction or demolition cannot deprive an eligible person of his right to vote,” emphasising that voting rights are tied to citizenship and residency, not property ownership. Sarma’s policy, which equates eviction with loss of voter status, appears to bypass these principles. In a notable case in Kachutali village of Kamrup district, over 1,000 residents — many evicted in a violent September 2024 drive — received notices threatening voter list deletion because they had “ceased to be ordinarily resident” in the constituency. This move, affecting one-third of the area’s voters, underscores the scale and intent of the policy.

For marginalised communities, particularly Bengali-speaking Muslims who have long faced suspicion as “foreigners,” these hurdles can be insurmountable

Even convicted criminals retain voting rights in India unless explicitly disqualified by law, such as in cases of electoral fraud or imprisonment for specific offences under the Representation of the People Act, 1951. By contrast, encroachment — a civil or administrative issue — lacks a clear legal basis for voter disenfranchisement. Human rights advocates argue that Sarma’s policy risks violating constitutional protections, potentially pushing marginalised groups into statelessness or prolonged legal battles to restore their voting rights.

Sarma’s rhetoric and actions cannot be divorced from their communal undertones. His repeated references to “Bangladeshi-origin Muslims” and “land jihad” — a term rooted in Hindutva conspiracy theories — frame the eviction and voter purge as a battle against a specific religious community. This narrative aligns with the BJP’s broader political strategy in Assam, where communal polarisation has been a tool to consolidate support among indigenous Assamese groups ahead of the 2026 State Assembly elections. By portraying Bengali-speaking Muslims as threats to Assam’s demography, Sarma taps into historical grievances while deflecting attention from systemic issues like poverty and land scarcity.

Selective Enforcement

The policy also raises questions about selective enforcement. Sarma has clarified that indigenous communities like the Moran, Mottock, Ahom, Gorkha, and Koch-Rajbongshi, who have resided in areas like Margherita for generations, will be granted land rights and spared from eviction. This distinction, while ostensibly protecting indigenous rights, implicitly targets Muslim settlers, many of whom have lived in Assam for decades, if not generations, and may possess legacy documents from the 1951 NRC or pre-1971 electoral rolls. The selective application of voter list deletions risks deepening communal divides and entrenching systemic discrimination

The human toll of this policy is already evident. In Kachutali, evicted families like that of Ibrahim Ali, a 33-year-old driver, face not only homelessness but also the loss of their democratic voice. Re-registering as voters in a new constituency is fraught with challenges, including bureaucratic scrutiny of documents and potential discrepancies in names, ages, or addresses. For marginalised communities, particularly Bengali-speaking Muslims who have long faced suspicion as “foreigners,” these hurdles can be insurmountable. Civil society groups warn that such measures could exacerbate social exclusion, leaving thousands vulnerable to exploitation and statelessness.

The policy also undermines the spirit of the NRC, completed in 2019, which aimed to settle questions of citizenship in Assam. By tying voter rights to eviction, Sarma effectively reopens these wounds, casting doubt on the legitimacy of citizens who have already navigated the arduous NRC process. The exclusion of over 19 lakh people most of whom are Hindus from the NRC’s final list remains a contentious issue, and this new policy risks compounding their precarious status.

By framing himself as the sole arbiter of who can vote, Sarma risks undermining the ECI’s authority and the democratic checks and balances that protect citizens’ rights. Critics, including Congress leader Aman Wadud, argue that this approach reflects a “king-like” mindset, prioritising political expediency over constitutional norms.

Assam’s policy sets a dangerous precedent for other States, where land disputes and demographic anxieties could be weaponised to disenfranchise specific communities. If eviction becomes a basis for voter list deletion, it could embolden governments to target minorities, migrants, or other vulnerable groups under the guise of administrative action.

Assam’s history of ethnic and communal tensions demands nuanced solutions that balance indigenous concerns with the rights of all citizens. Instead, Sarma’s policy risks escalating conflict, alienating communities, and tarnishing India’s democratic credentials. The ECI must intervene to ensure that voter list revisions adhere to legal and constitutional standards, preventing arbitrary disenfranchisement.

By framing this policy in communal terms, targeting Bengali-speaking Muslims as “infiltrators,” Sarma not only deepens social divides but also challenges the constitutional principles that underpin India’s democracy. Voting is a fundamental right, not a privilege to be revoked at the whim of a State government.

As Assam navigates its complex demographic landscape, the focus must shift from divisive rhetoric to inclusive governance that upholds the rule of law and protects the rights of all its people. The nation watches, wary of the precedent this sets for democracy itself.

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

- Tags

- assam

- Bengali muslims

- Bihar SIR

- CAA

Related News

-

Deadly avalanche kills eight skiers in California

3 hours ago -

Ayodhya priest questions Telangana govt’s Ramzan relief move

3 hours ago -

Titans emerge champions in sixth Samuel Vasanth Kumar memorial basketball tournament

3 hours ago -

Hyd Open golf championship to kick off from February 19

3 hours ago -

Jammu and Kashmir enter Ranji Trophy final with win over Bengal

3 hours ago -

Telangana High Court seeks ground report on forest plantation at Damagundam

3 hours ago -

Sahibzada Farhan century powers Pakistan to big win over Namibia

3 hours ago -

Chief Minister’s Cup 2025 sees record participation across Telangana

3 hours ago