Opinion: Caste Census needs legal validity — case for amending Census Act

Caste enumeration must adopt a scientific and legally protected approach — not just for accuracy, but to avoid political distortion and constitutional violations

By Dr Vakulabharanam Krishna Mohan Rao

India is home to one of the most socially, culturally and economically diverse populations in the world — comprising Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), denotified tribes, semi-nomadic communities, pastoral groups, artisan castes, fisherfolk, forest-dwelling communities, and hundreds of region-specific backward classes.

Also Read

In a nation of such layered identities, caste remains a deeply sensitive issue, closely tied to access, dignity and opportunity. It is not merely a political demand — it is the lived experience and long-pending aspiration of crores of OBC citizens who have been waiting for recognition and justice through proper data.

That is why, from the very beginning, any attempt at caste enumeration must adopt a scientific, methodical, and legally protected approach — not just for accuracy, but to avoid political distortion and constitutional violations.

In this context, the Narendra Modi government’s announcement in April 2025 — that caste data will be officially included in the forthcoming general Census — is a historic and visionary step. To give this effort legal validity and policy utility, a statutory amendment to the Census Act, 1948, is essential.

Why SC/ST Data is Counted, but OBCs are left out

SC/ST enumeration is permitted because:

- Articles 341 and 342 empower the President to notify SC/ST lists.

- These lists are integrated into every General Census via rules under the Census Act, 1948.

- The Registrar General of India (RGI) includes SC/ST status in each decennial census.

- Courts have upheld SC/ST data as essential for implementing constitutional protections.

In contrast, OBC enumeration is not allowed because:

- The Census Act, 1948 does not mention “OBC” or caste.

- Section 8 has no rules authorising caste enumeration beyond SC/ST.

- No nationally notified OBC list exists for this purpose.

- Indra Sawhney (1992) and Vikas Gawli (2021) emphasised the need for quantifiable data, but under proper legal framework.

- While Article 342A(3) empowers States to identify OBCs for their own purposes, this provision does not currently extend to centrally governed census procedures or ensure uniformity across the country.

This gap means that OBCs, who likely form the largest single social category in India, remain statistically invisible in our national development planning.

SECC-2011: A Failed Exercise

The Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC–2011) was the first post-Independence attempt to collect caste data, but it failed due to serious structural and legal flaws. It recorded over 46.73 lakh caste and sub-caste names, many of them invalid, inconsistent or unclassified, due to the absence of a standard coding or verification framework.

Although an Expert Committee under NITI Aayog Vice-Chairman Arvind Panagariya was constituted in 2015 to process and classify the data, it never submitted a report. Importantly, the SECC was conducted by the Rural and Urban Development Ministries — not under the Census Act or the Registrar General — making it legally and statistically non-binding.

Despite spending over Rs 4,893 crore, the caste data was never released and is unusable for constitutional or policy purposes. This failure clearly demonstrates that without constitutional authority, statutory process, and expert validation, caste enumeration lacks both legitimacy and utility.

Parliament must Legislate, not Delegate

In the Delhi Laws Act (1951) judgment, the Supreme Court held that Parliament cannot delegate essential legislative functions to the executive. Since caste census affects rights under Articles 15(4), 16(4) and mandates under Article 340, it must be enacted through legislation, not left to administrative discretion or executive notifications.

This makes the case for amending the Census Act, 1948, not only necessary — but constitutionally non-negotiable.

Constitutional Mandate

Caste enumeration aligns with the Indian Constitution’s vision of equality and justice. It draws support from:

- Article 14: Equality before law

- Article 15(4): Advancement of socially and educationally backward classes

- Article 15(5): Reservation in private educational institutions

- Article 16(4): Reservation in public employment

- Article 38(1): Social order based on justice

- Articles 39(b), 39(c): Equitable distribution of wealth and resources

- Article 46: Welfare of SCs, STs, and weaker sections

- Article 31-B: Ninth Schedule protection for affirmative laws

- Article 31-C: Immunity for laws implementing Directive Principles

- Articles 243D(6), 243T(6): Reservation in Panchayats and Municipalities

A caste census, if rooted in law, would be a practical application of constitutional morality and Directive Principles of State Policy.

What Government Must Do

Amend the Census Act, 1948: Introduce a clause explicitly authorising caste enumeration with legal backing and protections.

Frame rules under Section 8: Define caste categories, data security norms, and verification protocols to prevent errors and misuse.

Notify a national OBC list: Jointly developed by the NCBC and state BC commissions to ensure uniformity and legitimacy.

Digital tools and training: Use AI-backed multilingual tools and citizen-friendly portals for transparent enumeration.

Public trust and transparency: Publish clear timelines, use real-time dashboards, and engage civil society observers to ensure citizen confidence.

Institutional oversight: Establish a Ministry for OBC Affairs or a permanent Caste Enumeration Division under the Registrar General of India.

From Data Invisibility to Empowered Policy

Without caste data:

- Articles 15(4), 15(5), 16(4), 340 remain under-implemented.

- Articles 243D(6) and 243T(6) cannot support rational political reservation.

- Central and State governments remain dependent on outdated estimates or SECC-like flawed data.

Data is not just numbers — it is a tool of empowerment, legitimacy and constitutional delivery.

Legislating Equality, Building Unity

The Modi government’s announcement is not merely administrative — it is a moral and constitutional opportunity. A properly legislated caste census will not divide the nation — it will unite us through evidence-based justice.

Let every backward caste and community — from the agricultural labourer to the forest-dwelling tribe, from the street vendor to the weaver — be seen, counted, and empowered through policy.

Let us not just promise justice — let us legislate it.

(The author is former Chairman, Telangana State Commission for Backward Classes)

Related News

-

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

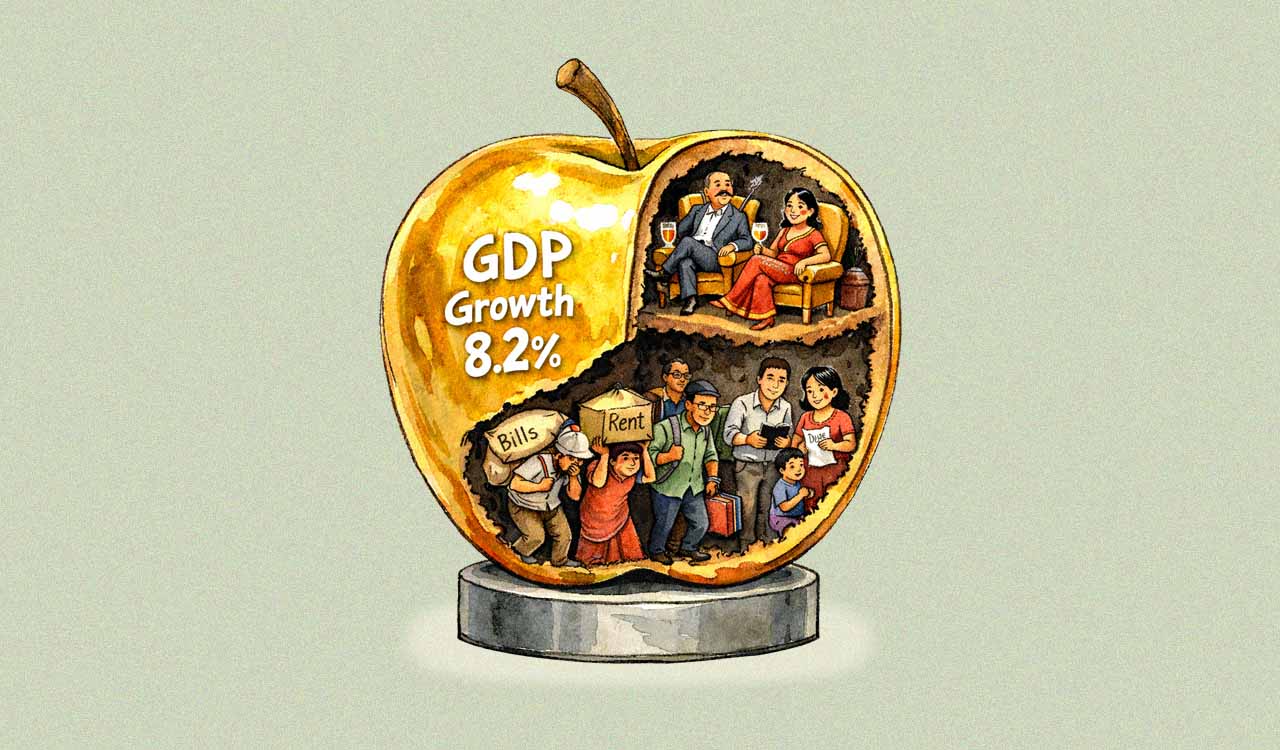

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Van overturns after tyre burst, 15 wedding guests injured in Nirmal

7 mins ago -

Gold slips on strong dollar, silver rebounds on MCX; Rupee hits record low

9 mins ago -

Young government job aspirant dies by suicide in Mancherial

10 mins ago -

KTR pays last respects to Kavuri Sambasiva Rao

13 mins ago -

Baloch militant group vandalises gas pipeline transporting fuel to Karachi

18 mins ago -

Licensed surveyors meet KTR, complain of no work or salary

20 mins ago -

Gulf crisis: GAIL halts gas supply to Yelahanka power plant; generation may be hit

30 mins ago -

Khot Lakhpat, Attock camps reactivate as Khalistani groups eye narco funding

44 mins ago