Opinion: Decolonising Indian Education— Rethinking what we teach and why

True decolonisation reshapes not just what we teach, but what we choose to value in learning itself

By Dr Sonal Mobar Roy

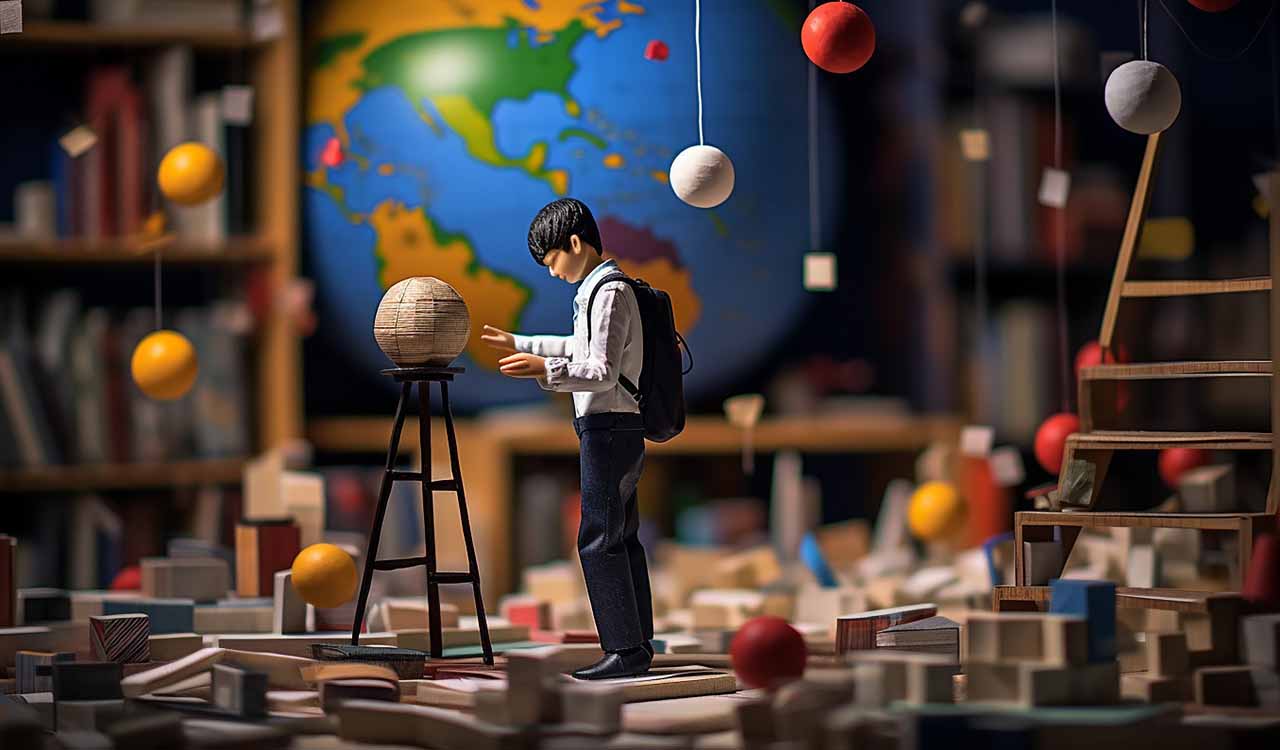

India’s classrooms still carry echoes of a past that wasn’t entirely ours. Much of what we teach, and how we teach it, comes from an inherited script — one that often places polished, distant knowledge above the messy wisdom of lived experience. For too long, education has privileged the abstract over the local, the universal over the particular.

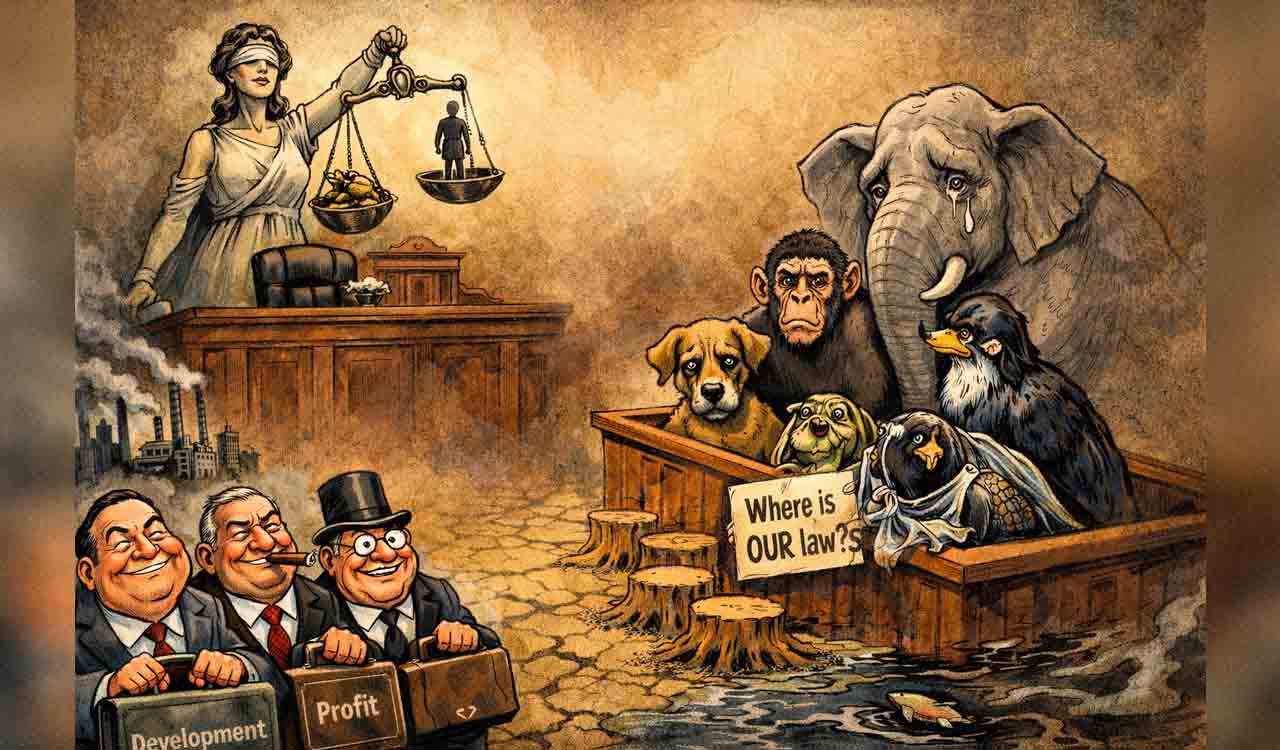

So, when we speak of decolonising education, it is not just about sprinkling folk tales into textbooks or renaming old institutions. It is about asking harder questions: Whose knowledge counts? Whose voice shapes the syllabus? And what kind of learners are we trying to create? Decolonisation, at its core, is a quiet but radical act of reimagining what we value in our pursuit of learning.

Our Vedic and traditional knowledge needs a complete come-back and a warm acceptance. Indigenous knowledge systems are not just cultural footnotes; they are living ways of understanding the world.

Across the country and its hinterlands, we still have those sky-gazing eyes of farmers who read the sky like a map, grandmothers who carry generations of healing in their wrinkled hands, and artisans whose work tells stories no textbook could hold. Their knowledge is not just beautiful — it’s useful, especially in a world grappling with climate change, fragile ecosystems, and fractured communities.

One needs to pause, observe, listen, and feel to realise that achieving SDGs is actually not that difficult. However, they have been sidelined and long-dismissed as informal, non-academic, or simply not modern enough. A decolonised education does not add them in as an afterthought. It starts with them. It recognises that how we live, grow, and learn depends on whose knowledge we choose to honour.

From NEP to NCF: A Quiet Shift Gains Ground

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 rightly acknowledges the imbalance in our knowledge systems and calls for multilingual learning and culturally rooted teaching. However, policies do not change classrooms on their own. That shift is now beginning with the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2023, which puts NEP’s ideas into motion. The NCF weaves Indigenous knowledge into subjects like environmental science, social studies, and ethics, ensuring students are harbouring the essence of their thought process.

The push for experiential, localised learning marks a move from symbolic gestures to pedagogical reorientation. What’s needed now is a sustained commitment to what may be called pedagogies of proximity — approaches that shorten the cultural and cognitive distance between the learner and the curriculum.

These are not just methods but mindsets where education is embedded in place, language, and lived experience. Much still depends on the teacher’s capacity, curricular materials, and institutional support. The University Grants Commission (UGC) is putting rigorous efforts into this plan. The momentum is real but fragile.

Guard Against

These shifts are worth celebrating, but they call for care. Indigenous knowledge is not just a discourse — it actually cuts through the thematic layers of regions, castes, genders, and livelihoods. If decolonisation becomes a way to centre only on dominant traditions, we stand at a risk of trading one form of exclusion for another.

It’s not just about adding new content; it’s about rethinking who delivers in the classroom, how and what, and whose voices shape the classroom. Are teachers free to draw from local wisdom? Do students get to explore the knowledge rooted in their communities? That’s where real change begins. Are oral traditions treated with the same seriousness as printed text? These are the deeper questions we must address.

Decolonising education isn’t about adding folk tales to textbooks or renaming institutions — it’s about who gets to teach, what knowledge we prioritise, and whose voices shape the classroom

As India moves rapidly towards a Digital University ecosystem and AI-powered educational platforms, there is an opportunity — and a lurking challenge. The question that arises is whether our digital education platforms can truly hold the richness of Indigenous knowledge or will they flatten it into standardised, searchable formats? Decolonising education in the digital age means making sure that we do not just move to an online platform but also perpetuate spaces that are multilingual, interactive, and culturally rooted.

A Forward Agenda

To move decolonisation from policy to practice, a few grounded shifts are needed. First, we need translational pedagogies, spaces where community elders and teachers co-design lessons, especially in areas like environment, health, and local history. Second, schools should host local knowledge labs, where students document and share the traditions around them, turning learning into real civic engagement.

Third, teachers must be trained in epistemic pluralism—learning how to teach diverse knowledge systems with care and academic rigour without romanticising or sidelining them. Fourth, open-access, multilingual platforms for Indigenous knowledge can make such resources accessible, respected, and widely used.

Finally, young people must be part of the process through projects like video ethnographies, crowdsourced glossaries, and innovation challenges rooted in their contexts. These steps can help make decolonisation not just a slogan but a living, inclusive practice.

Rooted Learning

India’s knowledge traditions aren’t about going backwards; they’re about moving forward with deeper roots. In a world facing climate stress, mental health challenges, and a growing disconnect from the locals, a decolonised education offers more than cultural pride, it offers lived wisdom. NEP 2020 and NCF 2023 point us in the right direction, but the path ahead will need care, creativity, and collaboration.

The real question isn’t whether Indigenous knowledge belongs in the classroom — it’s whether our classrooms are ready to hold what that knowledge has to offer truly. Education is not just about transmitting knowledge but about reproducing society. The question is: whose society are we reproducing? And if we must modernise, let it not be at the cost of memory.

After all, even Bourdieu would agree that habitus changes, but only when the field allows for new rules of the game. It’s time we updated the syllabus… without uninstalling the soul.

(The author is an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj [NIRDPR], Hyderabad. Views are personal)

Related News

-

This is taxpayers’ money: Supreme Court raps freebies culture

21 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Residents oppose Gandhi Sarovar Project over ‘forcible’ land acquisition

33 mins ago -

Australia level series as Indian women slide to 19-run defeat in second T20I

47 mins ago -

Karnataka beat Uttarakhand in semis, to face Jammu and Kashmir in Ranji final

52 mins ago -

Five Osmania varsity players in South Zone squad for Vizzy Trophy

1 hour ago -

Disciplined West Indies bundle out Italy with ease, tops Group C in T20 WC

1 hour ago -

Zimbabwe shock Sri Lanka to enter super eights, African team’s sublime run continues

1 hour ago -

ACB finds irregularities during surprise check at Dundigal municipal office

1 hour ago