Opinion: Elections expenditure and economy

By Nayakara Veeresha The Law Commission of India in its draft report has stated “saving public money” as one of the main reasons for recommending simultaneous elections. India’s 17th general elections in 2019 cost the public exchequer over $6.5 billion, ie, more than Rs 6,500 crore. This expenditure is more than the cost incurred in […]

By Nayakara Veeresha

The Law Commission of India in its draft report has stated “saving public money” as one of the main reasons for recommending simultaneous elections. India’s 17th general elections in 2019 cost the public exchequer over $6.5 billion, ie, more than Rs 6,500 crore. This expenditure is more than the cost incurred in the presidential and congressional elections in 2016 of the United States of America.

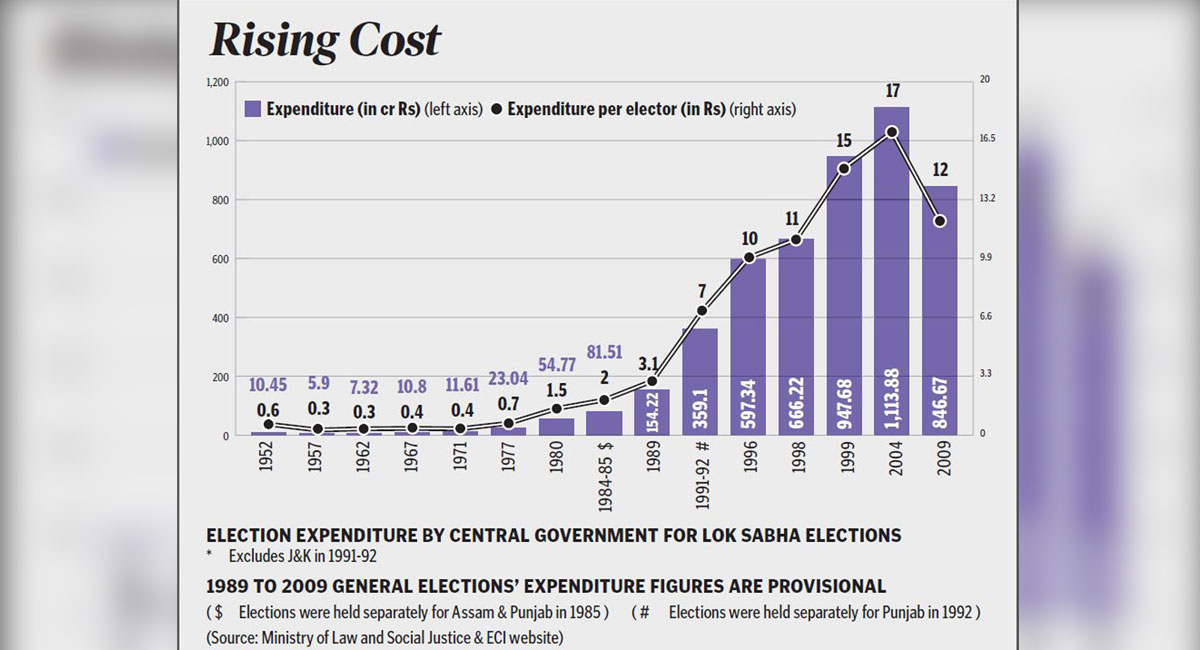

These calculations were done by Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. As per these figures, the elections of 2019 were the most expensive in the world. The election expenditure incurred for the first general elections was Rs 10.45 crore as per the Election Commission of India.

Public Spending

In the general elections of 2014, the government of India spent Rs 3,870 crore as compared with Rs 1,114 crore in 2009. Against this backdrop, it is necessary to look into the aspects of rising election costs and their implications on fiscal governance.

One of the core principles of fiscal management theories is improving the efficiency of public spending. The role of money and its influence in politics do not augur well for democracy and economic growth.

In the 1952 elections, Rs 0.6 was the expenditure incurred per elector; this increased to Rs 46.4 in 2014 elections. The post-1996 elections saw a gradual increase in the expenditure per elector. The pattern and trends indicate that the cost may have crossed Rs 70 per voter in the 2019 elections. As per the report of the Centre for Media Studies on Poll Expenditure, 2019, “on an average, nearly Rs 100 crore per Lok Sabha constituency, has been spent. Overall, it is estimated about Rs 700 per vote was spent in 2019 elections”.

Fiscal Deficit

The question is how does this rise in election expenditure affect the economy in the long run and its consequences to the fiscal stability, especially for the new regime? Historical data analysis of the Reserve Bank of India shows that the widening of fiscal deficit is the immediate impact of the increased election cost. Taking into account government spending before the Lok Sabha elections, out of 11 elections, seven times the fiscal deficit has widened since 1977. Fiscal deficit for the first time reached 1% in terms of GDP in the financial year 1998 and reached a maximum of 3.4% in 2009 (Nikita Kwatra).

In three financial years (FY), 1989 (-0.3), 1996 (-0.6) and 2004 (-1.4), fiscal deficit declined. The deficit of the current FY stands at 3.3%, which is slightly lesser than that of 2009. The foregoing figures and analysis infer that the rise in election cost widens the fiscal deficit owing to the increased government expenditure in conducting elections. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission (SARC) in 2008 and the Law Commission of India in its 255th report on electoral reforms in 2015 suggested an array of reforms in election finance. Apart from the election expenditure, the announcement of populist schemes before the elections is another factor which exerts fiscal pressure.

The average government expenditure preceding two years to the elections FY increased substantially in post-1996 elections augmenting the correlation between rising election cost and the widening fiscal deficit gap between estimated and actual expenditure. This is evident from the budgetary expenditure which has seen a deviation from the estimated budgetary allocations during the regimes NDA-I and UPA-I.

It is interesting to note that whenever the government has spent more in terms of subsidies and populist programmes, then they are able to retain the power in the ensuing elections. The UPA-II regime did not spend much during the 2014 elections FY which might have affected the electoral prospects paving the way for the NDA to come to power in 2014.

Being Wiser

Deviations from The Representation of the People Act of 1951 (RPA) regarding the political funding and cap on election expenditure are effectively contributing to the rising election expenditure of the government. The increased role of money, both in terms of government expenditure and political parties spending, puts constraints on long term economic growth.

The security cost of conducting elections in sensitive areas, increased cost of logistics and other expenses are only supplementary to the actual government’s expenditure, which rose from Rs 10.45 crore in 1952 to Rs 6,500 crore in 2019. This violates the provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act of 2003, especially Section 4 of (2) and (3). There must be harmonisation of the election expenditure with that of budget allocation to arrest fiscal deficit and strengthen fiscal stability of the economy and sanctity of elections.

Electoral Funding

Given the economic costs of conducting elections, it is necessary to institute certain measures to curb the role of money in elections. The Election Commission must be empowered to disqualify candidates by amending Section 77 (1) and disqualify those who fail to adhere to the provisions of Sections 78 and 10(A) of the RPA.

One of the ways to bring electoral finance reforms is to enhance transparency and accountability of seeking votes on the basis of performance of the party or individual in delivering governance and development outcomes in their respective constituencies. This not only restricts the role of money in elections but also encourages good and honest people to enter legislatures.

There must be internal accounting practices among political parties. Bringing electoral funding under the Right to Information Act and right to delivery of services in both pre and post poll by the parties may effectively reduce electoral costs. The heavy inclination of the electoral bond scheme towards ruling dispensation needs reforms for inclusiveness in political funding.

The author is PhD Fellow, Centre for Political Institutions, Governance and Development, Institute for Social and Economic Change [ISEC], Bengaluru. Views are personal

Related News

-

Opinion: MLA is not a Public Servant — justice lost in interpretation

-

Opinion: UGC Equity Regulations, 2026 — Contrary to the equity principle

-

Opinion: Presidential Reference verdict — Supreme Court’s missed opportunity to strengthen federalism

-

PM Modi invites Jordanian firms to partner with India, create economic corridor

-

Harry Brook century leads England to T20 World Cup semi-final with win over Pakistan

3 mins ago -

Editorial: Maoist movement in India — a Red sunset on the horizon

1 hour ago -

Mild tension in Hyderabad’s Attapur after cattle vehicle collides with truck

1 hour ago -

Telangana students among top scorers in JEE Main BArch and BPlanning

2 hours ago -

Students can enter Telangana Intermediate exam centres without signatures

2 hours ago -

From QR codes to hall tickets on WhatsApp: Telangana rolls out new initiatives for Class X exams

2 hours ago -

Osmania University explores collaboration with Dakota State University

1 hour ago -

Hyderabad Task Force nabs two suspects in Koti ATM robbery case

2 hours ago