Opinion: Making access to knowledge a right — is banning shadow academic websites the solution?

One Nation One Subscription covers only a fraction of institutions, and the ban on ‘shadow’ websites denies millions access to affordable research

By Marie Joseph Gerard Rassindren, Neeraj Kumar

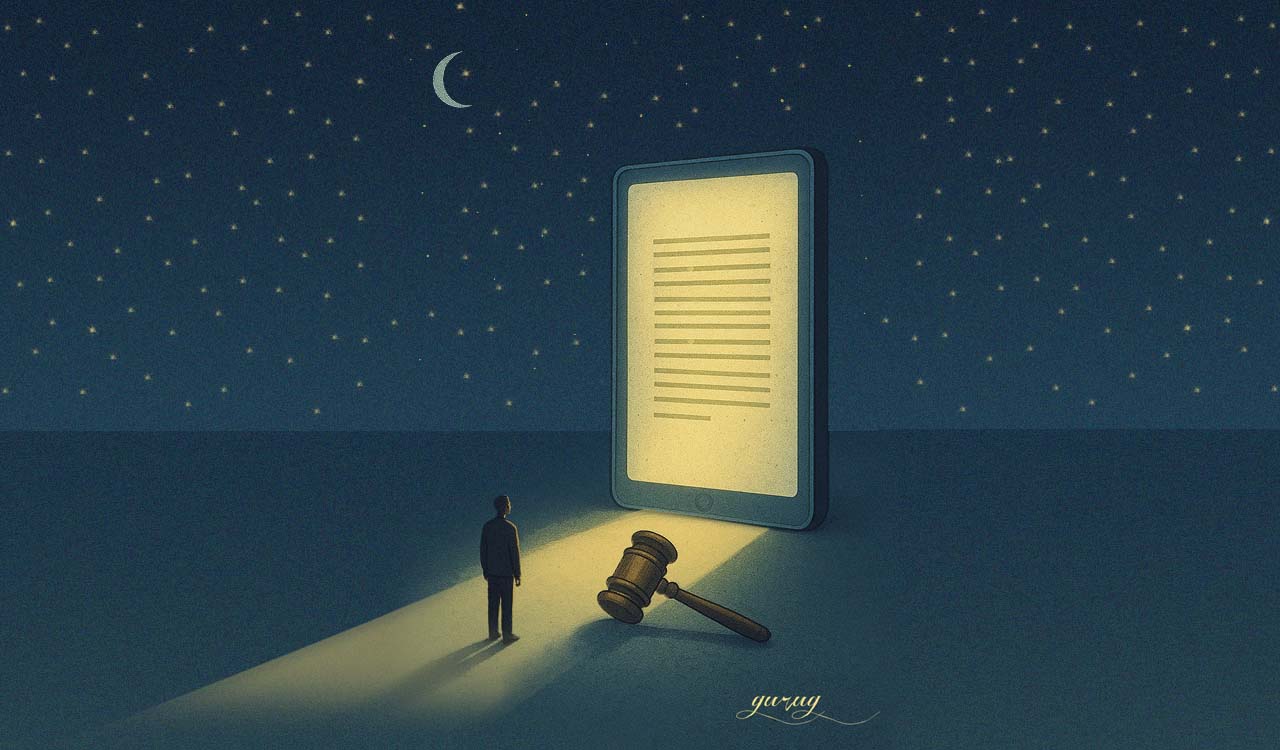

In 2025, two landmark developments reshaped India’s research and knowledge landscape. The year began with promise as the government rolled out the One Nation One Subscription (ONOS) scheme in January, a progressive step towards democratising access to academic journals and research databases. Yet just months later, the Delhi High Court’s August verdict banning Sci-Hub and similar platforms undercut that very vision, effectively closing the gates of knowledge for thousands of students and researchers.

Also Read

The ONOS dashboard reveals only 7,318 registered institutions, 98,44,128 users, and just 1,81,795 teachers covered. According to the AISHE’s 2021-22 report, India has 1,168 universities, 45,473 colleges, 12,002 standalone education institutions, 4.33 crore students, and 15.98 lakh teachers. Large institutions such as central universities, IITs, and IIMs, which can afford expensive journals and academic repositories, make up only a small proportion of this vast education ecosystem. By comparison, the coverage of ONOS is clearly falls short.

High Court’s Judgement

Against this background, it becomes imperative to examine the Delhi High Court’s judgement and its broad implications for research accessibility. The judgement prohibiting Sci-Hub and such platforms — popularly called shadow libraries — means no Indian, individual, as well as teaching and research professionals, can access these websites for sourcing content. The websites mostly host research papers, conference proceedings, book chapters, and reports. The companies that filed complaints against them were Elsevier and Wiley, both profit-driven commercial publishers of academic research.

The Delhi High Court relied on the UTV Software Communication Ltd & Ors vs 1337x.To & Ors case as a key reference to treat these websites as copyright violators. However, that case dealt with movies and entertainment content, not scholarly knowledge. In effect, the judgement seems to compare apples and oranges, wrapped in the fine print of legal statutes. The larger issue here is not just copyright, but access to knowledge and the rising cost of education.

The powerful commercial academic publishing industry has turned access to knowledge into a profitable commodity, making it a privilege rather than a right

Education and research go hand in hand. Besides classrooms and laboratories, libraries — digital or print — are crucial for accessing existing knowledge and generating new knowledge. One of the most significant components of the library infrastructure is access to the latest scientific studies and academic journals. These sources of knowledge have now become limited in availability and prohibitively expensive. In many developing countries, particularly India, access to important research papers is extremely difficult, especially for those in State universities and smaller colleges. This also gets aggravated when institutions cut down on their library funding.

Out of Reach

What does this mean to India’s educational space? It means many educational institutions and independent researchers cannot access cutting-edge developments because academic journals are expensive, and key research databases or repositories are costly. As a result, one cannot effectively build on existing knowledge. This creates a skewed and discriminatory global gap with regard to access to quality education and knowledge creation.

This problem stems not just from inadequate education funding but also from the commercial scientific publishing industry, an oligopoly dominated and controlled by a few transnational publishing houses. It is common knowledge that these publishers charge high article processing fees, often several thousand dollars. A 2023 study published in Quantitative Science Studies estimated that the global scientific community paid over $1 billion in open-access publication fees between 2015 and 2018.

The high article processing fees exclude researchers who cannot afford these charges. Moreover, there are ethical concerns. The authors must pay publishers to disseminate work created through intellectual labour, and by transferring copyright, publishers profit heavily from knowledge produced by researchers. This profit is rarely shared with the original creator. Individual journal articles are also sold at high prices, and the irony is, even the author may not be able to afford their own published paper, except for the author’s copy.

Breaking Paywalls

The powerful commercial academic publishing industry has turned access to knowledge into a profitable commodity, making it a privilege rather than a right. In this situation, avenues to access knowledge, either free or at an affordable cost, become essential if education is to remain a right. Websites that provide free access to academic papers, reports, conference proceedings, book chapters, even books and edited volumes, bypassing the paywalls erected by commercial publishers, aim to make access to knowledge and education a natural human right.

Importantly, when knowledge is shared, its supply or availability does not get reduced for the original holder. In this respect, the Delhi High Court’s judgement banning websites like Sci-Hub, SciNnet, LibGen fails to treat access to knowledge, especially research-related knowledge, as an educational right. Moreover, the entertainment industry copyright case cited cannot be equated with maintaining monopoly control over access to knowledge. The crackdown restricts researchers from going ahead with their work as it limits access to essential scholarly materials.

Where, then, should our attention lie? Should it be on these shadow sites, also called shadow libraries, or should it be on creating fairer access to academic knowledge? When we say fairer access, we mean comprehensive, equal, and affordable access. Our efforts and resources must be committed to:

- Increasing financial outlay for library resources;

- Expanding access to research databases for all affiliated colleges and State universities;

- Encouraging and funding open access publishing to make knowledge freely available; and

- Supporting ethical platforms that share educational resources legally.

Ultimately, our attention must shift from punitive action against shadow sites to building equitable and cost-effective ways that allow everyone to tap into the repository of knowledge, especially new and cutting-edge research.

(Marie Joseph Gerard Rassindren is Associate Professor and Neeraj Kumar is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Christ University, Bengaluru)

Related News

-

Australia offers refuge to Iranian women footballers amid war

27 mins ago -

Editorial: Nepal rejects the old guard

1 hour ago -

Telangana: Error mars Inter Physics II paper; question goes missing

1 hour ago -

Three-member burglar gang arrested in Hyderabad, stolen property worth Rs 13 lakh recovered

3 hours ago -

ACB catches Kukatpally community organiser taking Rs 18,000 bribe

3 hours ago -

90% of Hyderabad eateries likely to shut down in next 48 hours amid LPG crisis

3 hours ago -

Watch | Flash Strike by Sanitation Workers After CM Revanth Reddy’s Remarks

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Overseas consultancy manager murdered in Madhuranagar office attack

3 hours ago