Opinion: Missing voices in India’s workplace well-being

The debate on workplace well-being has largely focused on corporate employees, sidelining the informal sector that employs over 80% of the workforce

By Sai Abhijeet RV Ratnapark, Moitrayee Das, Shrirang Chaudhary

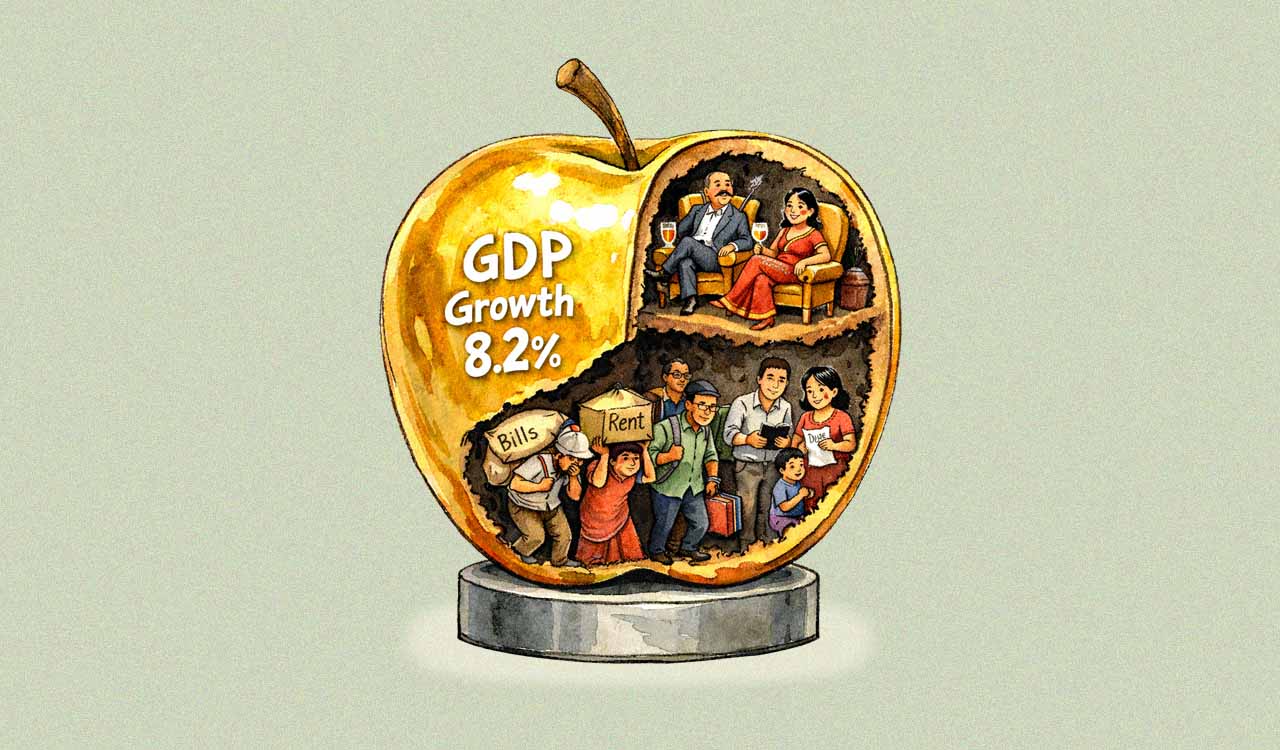

India’s informal sector, which employs over 80% of India’s labour force, remains largely invisible in public discourse on workplace practices and policies. The non-inclusion of their ‘voice’ continues to be conspicuous. Ignored, sidelined, and unheard, but till when? Is the question that ought to be asked.

Also Read

The recent wave of discussion on working hours sparked a debate among corporate leaders, professionals, influencers, and employees. What’s interesting is that the majority of these discussions focused on the organised sector, ie, corporate workplaces, and largely ignored the issues faced by informal workers.

Biased Narrative

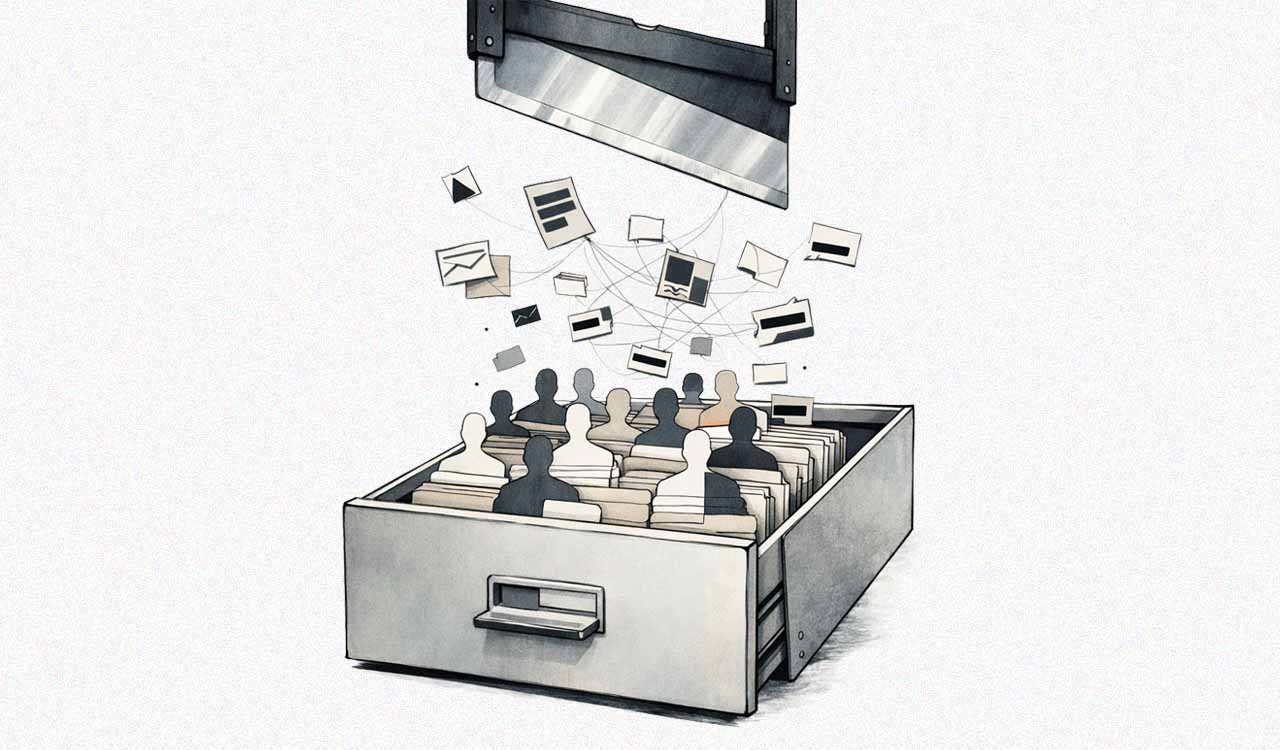

Given this, one must ask whether this debate was truly ‘inclusive’ or simply a series of arguments driven by ‘heuristics’. A random search on workplace practices and behaviour reveals articles focused on developments in the corporate world. Issues such as workplace stress, employee mental well-being, toxic behaviours by supervisors, long working hours, lack of voice, job loss, and health emergencies are being debated with the urgent need to improve policies and work culture. Given that the informal sector constitutes the largest proportion of the Indian workforce, its non-inclusion or limited mentions highlight the heuristics and biases at a macro-level, which in turn translate into an algorithmic bias.

One common argument during the working conditions debate concerned mental and physical fatigue resulting from increased working hours — for example, the case of the E&Y employee who passed away due to stress, exhaustion, and anxiety at work. (Pandit, 2024). The debate saw widespread participation.

Recent research paints a stark picture: most informal workers operate without contracts, paid leave, or social security, leaving them trapped in cycles of vulnerability and exploitation. Studies on construction workers show that excessive hours and hazardous environments are not exceptions but norms, with fatigue and workplace accidents rising steadily (OUP Academic, 2024).

Including informal workers as equitable stakeholders requires a detailed study of their working conditions, definitions of toxic and uninhabitable environments, and burnout, so that effective regulation can follow

In this context, the framing of the debate is telling. The entire narrative ignores informal workers, highlighting the ‘framing effect’ in psychology, a cognitive bias where people’s decisions and judgments are influenced by how information is presented, rather than by the information itself (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Research further suggests that when information is framed in terms of potential gains or losses, individuals respond differently, even if the underlying information is identical. Frames impact perception, emotional response, and risk evaluation (Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, 1998).

Framing of Debate

A clear demarcation that left informal workers out of the loop was the nature of the debate — social media! (Frame 1). The workplace well-being debate led to the usage of certain vocabulary, which changed the perception of corporate culture, work environments, and job expectations. Words such as ‘burnout’, ‘work-life balance’, ‘well-being’, and ‘hustle culture’ have become part of everyday language, normalising these working conditions that were previously not openly demanded by employees (Frame 2).

The debate escalated, flooding the internet with these terms and spotlighting the urgency of addressing formal work conditions. Meanwhile, the audience’s attention remained largely on the corporate workplace, overlooking informal workers, such as labourers, who have for years been ‘hustling’, experiencing burnout, and yearning for a work-life balance that essentially does not exist. This indicates how the informal sector has been pushed into the mute or chaotic background (Frame 3).

Thus, a debate with the potential to explore multiple dimensions peaked and subsided within one narrow focus, primarily serving the purpose of improving corporate work culture. The pressing priority is to expand perceptions towards the workplace beyond the formal, corporate sector. Data concerning informal workers supports this need. The Directorate General Factory Advice Service & Labour Institutes (DGFASLI) reported an average of 1,109 deaths per year in registered factories between 2017 and 2020. The Martha Farrell Foundation’s study reported 418 fatalities and 1,754 injuries across 65 informal sectors in India.

These numbers are alarming, and the “cherry on top” is that this data comes only from registered factories and companies, leaving out the vast majority of unregistered informal workers. Moreover, comprehensive and recent data on safety, risks, job loss, compensation, and benefits for informal workers is largely unavailable (Bandyopadhyay, 2023; Paliath, 2023).

While these reports speak volumes about the ignored realities of informal workers, a recent discussion by AAP MP Raghav Chaddha in the Lok Sabha highlighted the suspension of the ‘10-minute delivery service’. He emphasised how delivery workers have been transformed into robots, racing to deliver everything from ice-creams to hair dryers, often under harassment, hazardous working conditions — all for a five-star rating, a model that prioritises convenience over health and dignity.

Making Debate Inclusive

These challenges demand a revision of ownership, responsibilities, research, and policies. Including informal workers as equitable stakeholders requires a detailed study of their working conditions, definitions of toxic and uninhabitable environments, and burnout, so that effective regulation can follow.

The first step is to ensure that informal workers are included as integral participants in relevant conversations. These discussions must involve various stakeholders (a range of informal workers) and give them an adequate ‘share of voice’ by leveraging channels of mass consumption effectively using local and regional languages, to debunk biased narratives in the media.

Digital access is no longer a luxury but a necessity; hence, promoting digital literacy would put informal workers on the map.

Following this, two measures are essential:

- Policy revision: update nationwide policies governing informal workers, and implement safety, healthcare (including mental health) at subsidised rates.

- Organisational reforms: Introduce protective policies within organisations employing informal workers to provide more systematic and structured job responsibilities, and prevent 12-hour work shifts.

Implementing policies to regulate wages and working hours, while incentivising small and medium enterprises in both urban and rural areas, can significantly improve employees’ working conditions. A crucial reform needed is the active participation of the government, private, and public players in ensuring the inclusive representation of employees across social classes and structures. This participation must be driven by inter-class, inter-community, and industry-wide conversations — not limited to social media pages, isolated articles, or one-off posts, but through sustained, critical dialogue that involves lower socioeconomic groups, thereby adding nuance, depth, and equity to the conversation.

(Sai Abhijeet RV Ratnaparke is undergraduate student and Moitrayee Das is Assistant Professor of Psychology, FLAME University, Pune. Shrirang Chaudhary is Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at MIT World Peace University)

Related News

-

Gold dips during week amid profit booking, strong US dollar

6 mins ago -

Trump ‘loves India, Modi’, says Laura Loomer at India Today Conclave

42 mins ago -

BCCI Naman Awards 2026: Binny, Dravid, Mithali to receive lifetime honours

1 hour ago -

KKR unveil ‘Lines of Legacy’ jersey ahead of IPL 2026 season

2 hours ago -

Managing Cash Flow Through Overdraft Facilities Without Impacting Home Loan Eligibility

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Woman dies by suicide after killing son in Borabanda

2 hours ago -

SSC examinations begin on a peaceful note across Adilabad

2 hours ago -

Son appears for SSC exam hours after father dies in road accident in Medak

3 hours ago