Opinion: Shattered lives—the human cost of India’s migrants

India’s dependence on migrant labour to build its cities and drive its economy carries a responsibility to protect their health, safety, dignity, and welfare

By Kattamreddy Ananth Rupesh

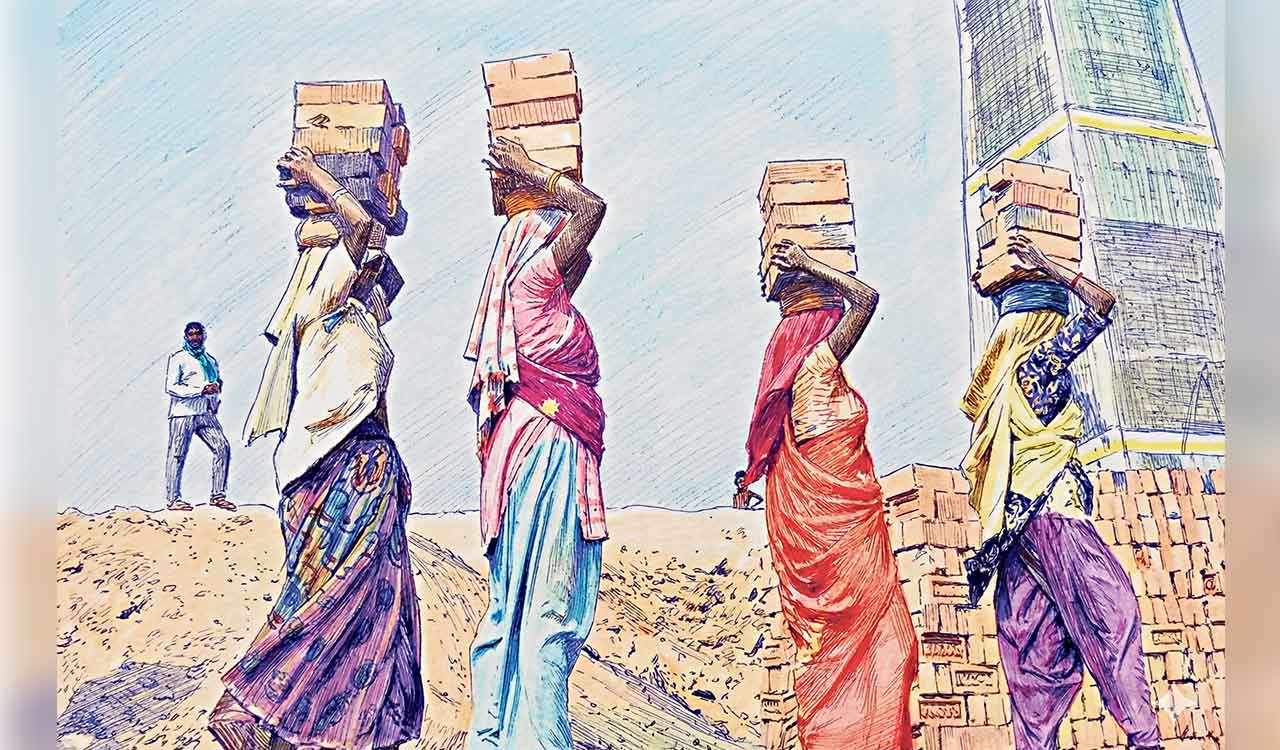

Homebound, India’s official entry for the 2026 Oscars in the International Feature Film category, captures the stark reality of internal migrant workers; men and women packed into overcrowded trains, labouring in hazardous factories, and surviving in cramped, makeshift settlements at the edges of our cities. What may appear to some as cinematic dramatisation is, in fact, an everyday truth. For any conscious citizen, these scenes are painfully familiar, echoing real bodies, real tragedies, and real despair.

The struggles of migrant labourers, their silent endurance, health issues and broken dreams reveal a harsh truth that in today’s India, the search for a ‘better life’ still remains a cruel and dangerous gamble to many. In spite of their vital contribution to India’s economy, internal migrants continue to face severe health vulnerabilities and inadequate protection, demanding policy and humanitarian attention.

Also Read

Internal Migration

The scale of internal migration in India is staggering. The 2020–21 MoSPI survey shows that about 28.9% of Indians are internal migrants, with around 26.5% in rural areas and a significantly higher proportion in urban regions. Of these, roughly 10.8% move primarily in search of work and livelihood. Current estimates place the overall number of domestic migrants at nearly 40 crore people — a massive population whose survival depends on stable employment, safety, and access to basic services.

Despite their vital contribution to the economy, the search for a ‘better life’ remains a cruel and dangerous gamble for migrants

While international migration is often driven by war, conflict, persecution, and geopolitical instability, migration within India has largely been a struggle for basic living. In a country where the upper-middle class and wealthy migrate abroad for opportunity and ambition, internal migration continues to be fuelled by necessity, not choice.

Migrant Health

Being counted as a migrant does not guarantee safety, health, or dignity. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), migrants, especially labour migrants, frequently suffer worse health outcomes than the general population because their living and working conditions often expose them to overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate hygiene, and unsafe working environments. These conditions increase vulnerability to diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis, and other communicable illnesses.

The same pattern is evident in India, where many internal migrants face chronic risks arising from strenuous work, long hours, poor nutrition, inadequate housing, and limited access to maternal or preventive care. This results in a higher incidence of both communicable and non communicable diseases, frequent injuries, and long term health complications. Such realities undermine the promise of migration as a path to a better life and run contrary to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, which emphasise universal access to health, decent work, and safe living conditions.

A multi-level analysis study by Tanushree Bhan and Amit Patel (2023) finds that migrants moving from rural areas to big cities in India are less likely to get minor illnesses like colds, but more likely to develop serious long-term diseases such as high blood pressure or tuberculosis, compared to those who move to smaller cities. Although these differences reduce over time, those who migrated to big cities after 2004 are more likely to face long-term health problems later. The research suggests that different types of cities need different healthcare plans to support migrant wellbeing.

Beyond Numbers

Beyond the statistics lies a tragic human cost — one I have witnessed repeatedly in my work as a forensic pathologist. In one instance, a young male migrant, overworked and exhausted, contracted a treatable illness such as dengue while working long hours in a factory. Weak and feverish, he attempted to return home, hoping to survive the journey, but perished en route on an overcrowded train, alone and unattended.

In another case, a young female migrant working in a stone quarry ended her life by hanging after losing her husband in a sudden workplace accident, leaving her without support or hope. These are not isolated tragedies; they are grimmer than what Homebound portrays and are quite common.

Among internal migrants, unnatural deaths such as suicides are distressingly common, driven by intense stress, social isolation, language barriers, loneliness, and the psychological burden of displacement. Accidental deaths are also common, particularly in informal sectors such as construction, quarries, and small factories where occupational safety norms are weak, and workers are easily exploited. Homicides, too, occur, often linked to substance abuse or the vulnerability of young migrants drawn into petty drug networks.

These unnatural deaths are reported more from socially marginalised communities. In cities across India, forensic pathologists and police often see migrant families unable to claim or transport their deceased due to severe financial hardship, exposing the deep socioeconomic vulnerabilities. Such experiences underscore the urgent need for occupational safety, healthcare access, social security, and, above all, human empathy.

State Responsibility

In recent years, the Indian government has introduced several schemes to support migrant and informal workers. The e-Shram Portal, launched in 2021, has registered over 30 crore unorganised workers, offering a “one-stop solution” for accessing multiple benefits, including food security through the PDS. Social security measures such as the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-Dhan (PM SYM) pension scheme provide old-age support, while States like Kerala, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu have introduced additional welfare schemes for migrants.

However, many workers remain excluded due to a lack of awareness, registration barriers, and limited outreach. Migrants are often left out of universal healthcare coverage, and occupational safety regulations remain weakly enforced in sectors where they predominate. Access to maternal and child healthcare is limited, living conditions are poor, and mental health outreach remains inadequate.

To bridge these gaps, employers, as mandated under recent labour laws, and state and local authorities must actively facilitate registration and benefit delivery. Health awareness campaigns, strict enforcement of safety norms, and provisions for housing, education, and childcare for migrant families require prioritisation.

The health vulnerabilities of internal migrants are neither new nor pandemic-induced. Even before Covid, studies showed poorer health outcomes, limited preventive and curative care, and higher morbidity and mortality among the migrant population. For many, migration becomes a cycle of exploitation, deprivation, and invisibility.

India’s reliance on migrant labour to build its cities and sustain its economy carries a responsibility to safeguard their health, safety, dignity, and welfare. Migrant-sensitive policies, accessible healthcare, safe housing, social security, and targeted public-health interventions are essential. Health systems must actively reach migrants through mobile clinics, urban-health programmes, and community-based services.

Films like Homebound may awaken us to this reality, but beyond watching, we must act to ensure that internal migration no longer means invisible suffering, and that every migrant has the dignified right to life, health, and hope.

(The author is Assistant Professor of Forensic Medicine, Government Medical College, Ongole, Andhra Pradesh)

Related News

-

Opinion: Skipping a Master’s degree may weaken research quality

-

Opinion: Prashant Kishor — the kingmaker who could not crown himself

-

Opinion: From strategic depth to strategic discord: Why the Taliban-Pakistan rift is reshaping the region

-

Opinion: India’s paraquat paradox, a poison still within reach

-

Khamenei’s son seen as contender as Iran faces leadership question

2 mins ago -

Over 13,000 skip Intermediate exams in Telangana

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Three held with MDMA in Miyapur

2 hours ago -

Telangana govt sets deadline for Singur canal works

2 hours ago -

Minister Surekha’s daughter Susmitha lays claim to Parkal Assembly seat

2 hours ago -

Revanth Reddy govt’s 99-day action plan clouded by funding ambiguity

2 hours ago -

Middle East Crisis: Flights to India partially resumed after five-day disruption

2 hours ago -

Harish Rao criticises Revanth Reddy for harassing officials with frequent transfers

2 hours ago