Opinion: No Animals… Will we have to walk alone?

Humanity often describes extreme violence perpetrated by humans upon each other as ‘animal rage’ or ‘animal acts’, creating a false distinction between human and animal

By Pramod K Nayar

For not even lions or dragons have ever waged with their kind such wars as men have waged with one another — St Augustine. When a human commits a heinous crime, the public discourse, and occasionally even the law, describes the perp as an animal. The perp – often male – is accused of returning to animal instincts, of being beastly, etc. The human is defined here as one who does not indulge her or his ‘animal instincts’, and when some do, the rest of us are shocked that they returned to their animal state of being.

Also Read

Language of Difference

The construction of a language through which such a difference can be created, repeated and enforced is the key to the distinction humanity makes between human and animal. Horrific acts by humans are described in animal or quasi-mystical terms. Thus, humanity will describe extreme violence perpetrated by humans upon each other as ‘animal rage’ or ‘animal acts’, or call them ‘demonic’ or ‘devilish’. Any act that humanity deplores as irrational or extreme is attributed to that perp’s difference from the rest of humanity, and is, therefore, either a devil, a demon, or an animal.

Humans promote the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’, the animals, in terms of presumed qualities, ranging from altruism to language — qualities that, apparently, animals do not possess. The rise of the human is built on the exclusion of all those qualities that then are called ‘animal’. It is, of course, humans who determine which qualities are higher-order qualities — language, awareness of mortality, humour — and which are animal qualities. That is, humans decide which qualities count and which do not.

This emphasis on difference, the philosopher Cora Diamond reminds us, can only be achieved by ignoring ‘overwhelmingly obvious similarities’, including vulnerability, suffering and mortality. The erasure of the similarities of animal and human, and the animality within humans, is the ‘originary violence’, as the philosopher Jacques Derrida argues, from which the hierarchy of human and animal begins.

The denial of animality within humans is integral to emphasising that what the humans possess is uniquely human, different from the animal. In the process, as numerous philosophers have noted, we humans subsume all the varieties of lifeforms under one category ‘the animal’, thus erasing the differences among them.

Animal is a word humans have given themselves the right to give others. The animal is an animot in Derrida’s French, where ‘mot’ means word. Humans have created the word ‘animal’, which we then assign to all lifeforms. Animality begins with the construction of a word to designate all the qualities and life forms humans did not want to be.

Seeing, Naming

Humans make much of the ability to employ language, although biologists patiently explain to us that animals do possess language, even if humans do not identify it as such. Humans argue that animals react and humans respond, and thus construct an untenable difference.

There is, so the argument goes, a specific reason why prisoners are hooded before being beaten or tortured because acts of dehumanisation are more difficult when the perp has to look into the eyes of the victim. Philosophers ask: ‘when I ask an animal a question and look him or her in the eyes, the animal answers, looks back’. That is a response, they argue. Animalisation, like dehumanisation, demands that we do not look the animal in the eye because then we may find that the animal responds, and thus establishes itself on the same plane as another human, making it more difficult to ignore or exterminate them.

Humans assert their uniqueness by denying their own animality, even as they subsume all other life forms under one category, ‘the animal’, thus erasing the differences among them

Observing animal behaviour experiments, commentators note that perhaps the experimenters are asking the wrong questions. After weeks of giving and sharing food, the experimenter stops doing so to see how the animal will respond to the cessation. The experimenter records assuming the animal is trying to find a way to get food from its previously generous human. They believe the animal is asking: ‘where can I find food?’But perhaps, argue the animal philosophers, the animal is asking: ‘why are you doing this to me now?’

Animals do not have to see us when they can sniff us. The over-emphasis of vision in humans, cultural historians like Martin Jay tell us, was linked to the idea of ‘illumination’, ‘insight’ and the ‘distanced’ or ‘objective’ observer and, of course, seeing as knowledge-source and believing. But neurobiologists tell us that it is because over the course of evolution humanity lost its sense of smell that vision arose to dominance.

So the question need not be what the animal sees when it looks at us, because we overvalue sight when the other lifeforms do not need to necessarily see in order to know. This dominance of vision as means of knowing itself creates the hierarchy between humans and other lifeforms.

Naming Suffering

The dominance of the human hinges on another erasure: the finitude we share with other life forms, from injurability to mortality. When Jeremy Bentham inaugurated the animal rights philosophy by pondering, ‘Can they [animals] suffer?’, the question has an unvoiced phrase too: can animals suffer as humans do?

But the problem, as Derrida reading Bentham suggests, humans ‘will contest the right to call that ‘suffering’ or ‘anguish’ because these are words or concepts that humans ‘reserve for man’. In other words, we are back to questions of language: do we call what animals experience ‘suffering’? For such philosophers, there is no doubt: they suffer.

When thinkers like Derrida and Cary Wolfe apply the term ‘genocide’ to what humans inflict on animals, they are well aware that they may be accused of misappropriating a very loaded term:

There are also animal genocides: the number of species endangered because of man takes one’s breath away…one should neither abuse the figure of genocide nor consider it explained away. For it gets more complicated…the annihilation of certain species is indeed in process…

When another life form follows us, as cats and dogs do with their eyes, it can also mean ‘to be after’ (following). But, as we know, numerous species on earth predate humans. That is, we have followed, come after these species. Now, respect for ancestors, the core of multiple belief systems, ought to then inform how we look at other life forms because humanity only follows them: they precede us.

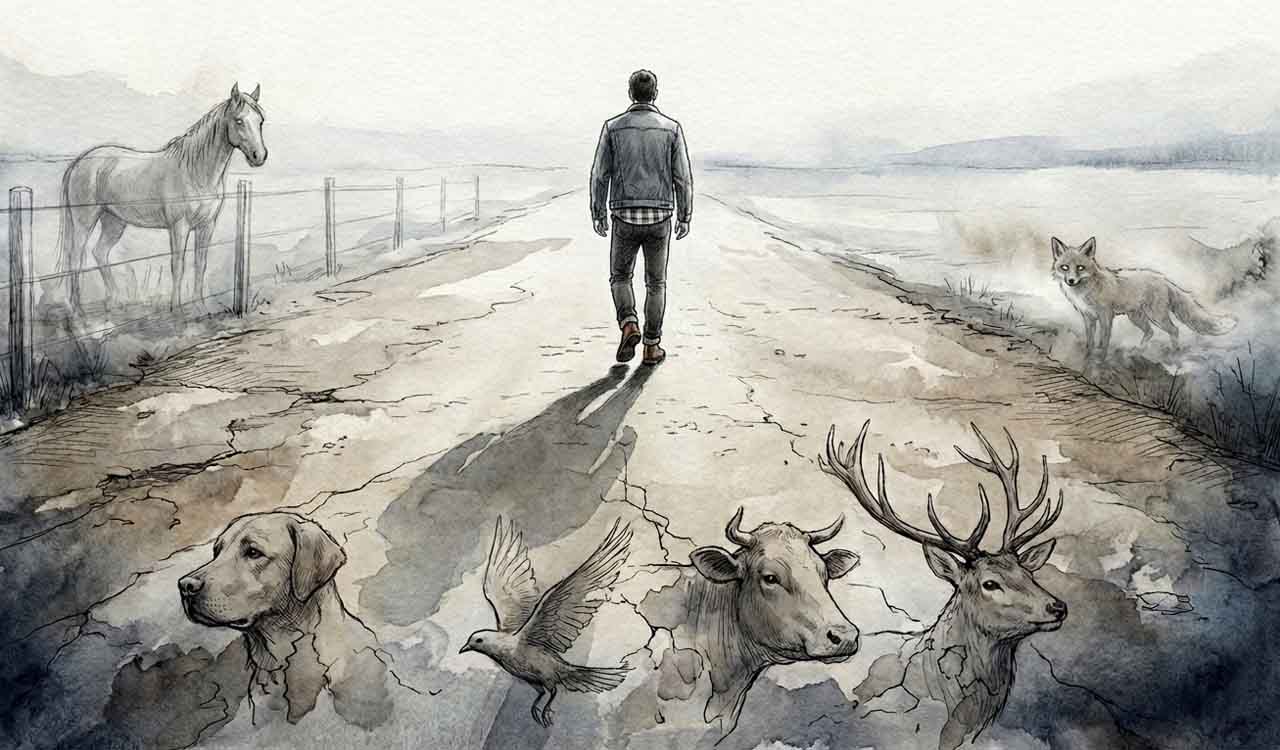

Right now, one life form watches (follows) the debates unfolding. We who follow these life forms who have preceded us, but who now are alongside us, walk with us, near us, also follow and watch the events. We, of course, have to adhere to — follow — the law. But what of those who do not understand the letter of the human law simply because they have always only followed us, down the mean streets, across the grounds, into our vision and lives?

Who will follow us when we ‘remove’ them from the streets? Whose eyes will we follow when we seek company beyond the human?

We shall have to walk alone.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Opinion: Skipping a Master’s degree may weaken research quality

-

Opinion: Prashant Kishor — the kingmaker who could not crown himself

-

Opinion: From strategic depth to strategic discord: Why the Taliban-Pakistan rift is reshaping the region

-

Opinion: India’s paraquat paradox, a poison still within reach

-

Iran, US have been at war for decades – there’s no end in sight

6 mins ago -

KTR distributes cheques to 16 MBBS students

20 mins ago -

Dalit activists protest demolition of Ambedkar statue platform in Siddipet village

13 mins ago -

Andhra govt takes measures to run 10 medical colleges under PPP mode in 2 financial years: Minister

41 mins ago -

X warns creators: Disclose AI war videos or face suspension

49 mins ago -

Video: Passengers escape unhurt as car catches fire on NH-65 in Sangareddy

39 mins ago -

West Asia crisis: Sensex, Nifty trade sharply lower

1 hour ago -

Asian shares swoon, Kospi sinks 12 pc, as war with Iran widens, oil surges higher

2 hours ago