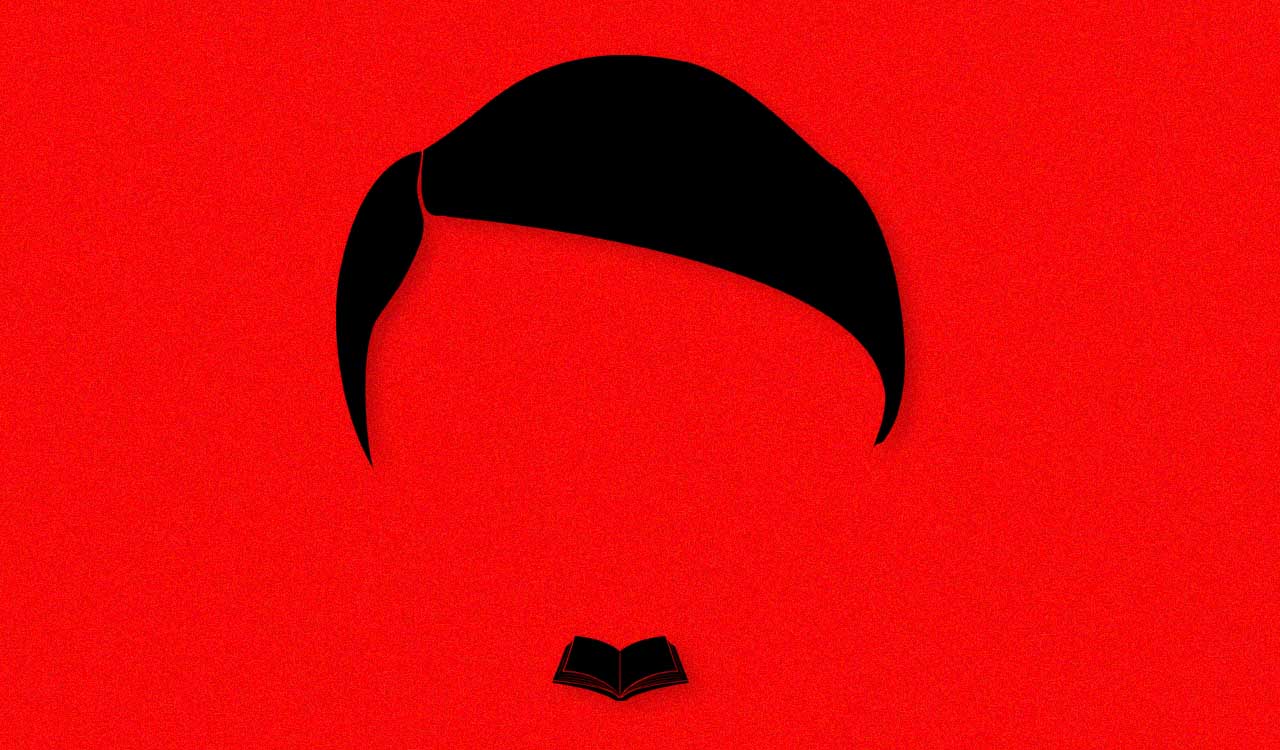

Rewind: Mein Kampf — Was this the book that launched a genocide?

We read Mein Kampf in its hundredth anniversary year with the wisdom of hindsight but also horror-struck at the Israeli state’s own actions now, fully aware of the nightmare reality Hitler’s vision spread across 700 pages produced

By Pramod K Nayar

George Orwell reviewing a new unexpurgated edition of Mein Kampf in 1940 wrote: What [Hitler] envisages, a hundred years hence, is a continuous state of 250 million Germans with plenty of “living room” … a horrible brainless empire in which, essentially, nothing ever happens except the training of young men for war and the endless breeding of fresh cannon-fodder … It is the fixed vision of a monomaniac.

Also Read

Orwell, of course, knew a thing or two about totalitarianism. He also observed that Hitler’s vision is unchanged:

When one compares his utterances of a year or so ago with those made fifteen years earlier, a thing that strikes one is the rigidity of his mind, the way in which his world-view doesn’t develop.

But the refusal to develop, to see other versions of the world, understand multiple interpretations, but keen on imposing one vision upon everyone marks the monomaniacal mind. Mein Kampf’s danger lies not just in its virulent racism and theories of racial superiority but its hermetically closed worldview.

Often described as ‘the most dangerous book in the world’, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf was published in 1925, and a hundred years later it remains unrivalled as a frightening manifesto of hatred, murderous intent and racism

As a book, it is not just a ‘totem of evil’ possessing ‘dark glamour’, as one reviewer commented in 2014, for it has to be read within the context of his speeches, first, and then the execution of this awful vision.

While it reflected the political realities of the period of its writing (1924-26), the manufactured adulation the work received, as Richard Evans notes in The Coming of the Third Reich, ‘helped convince Hitler…that he was the man to turn these views into reality’.

In its hundredth anniversary year, with the wisdom of hindsight but also horror-struck at the Israeli state’s own actions now, we know the reality Hitler’s vision spread across 700 pages produced. Indeed, commentators believe that the basis of all Nazi propaganda was Mein Kampf.

Prescribed Reading

The publishing and reading history of Mein Kampf is rather chequered. Some, like Albrecht Koschorke have argued that ‘foundational works of this kind are understood by dictators as essential to the task of cleansing’. Koschorke calls Mein Kampf the ‘first dictatorial book of the twentieth century’

The first part, dictated by Adolf Hitler to Rudolf Hess when they were both in prison from April 1 to 20 December 1924, appeared on 18 July 1925 priced around USD 3. The second part appeared in December 1926 and sold 13,000 copies. In 1930, a single volume called the ‘People’s Edition’ appeared. Following the victory of the Nazi Party and a circular drafted by Rudolf Hess, sales rose to 62,000.

From 1933, of course, ‘not to own a copy was almost an act of treason’, as Richard J Evans puts it. In 1934, the Prussian Minister of Education ordered the book to be used as a school primer. The Reich Railway Executive gave the book as a reward to its officials. Herman Goering ordered all civil servants to study the book and the Minister of the Interior recommended in 1936 that even consuls abroad should read the work.

How many people actually read Mein Kampf, even among Hitler’s acolytes, is a moot point, although after he came to power, it became almost an anti-national act not to own a copy. Dictators, apparently, have authorial desires too

Despite this mandated reading, as C Caspar notes in his 1958 essay on Mein Kampf as a ‘bestseller’, not even his close circle read Hitler’s book. Today, a hundred years later with multiple translations, Mein Kampf is an unreadable-but-widely-read bestseller, as people seek to understand the mind of the most infamous dictator in human history.

People who read it are branded neo-Nazis, anti-Semitic and even evil, usually by those who have not read it. Indeed, in 1957, in the House of Commons, the government’s spokesperson declared that the use of the book was in contravention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Conventions.

Growing up to be a Nazi

The first part of the book traces Hitler’s growing-up years, and the hardening of his world view. He claims he recognised very early the betrayal of the Germans by their rulers:

What history taught us about the policy followed by the House of Habsburg was corroborated by our own everyday experiences. In the north and in the south the poison of foreign races was eating into the body of our people, and even Vienna was steadily becoming more and more a non-German city.

Hitler also foregrounds the nationalist spirit he says he developed early:

I developed very rapidly in the nationalist direction, and by the time I was fifteen years old, I had come to understand the distinction between dynastic patriotism and völkisch nationalism, my sympathies being entirely in favour of the latter even in those days

He also states major claims for the development of his personality with declarations such as this: ‘a precocious revolutionary in politics, I was no less a precocious revolutionary in art’. Here Hitler offers a retrospective teleology. The narrative suggests that everything in Mein Kampf is geared towards the singularity of his future role as Chancellor of Germany, the hero of the German people, etc, as though the condition of being the supreme leader was the endpoint of both his life and of his autobiography.

Greatness is the goal towards which both his life and his writing moves. Even during his days of ‘struggle’ as a student in Vienna, Hitler claims he was alert to deeper structures of the social order and of life which then congealed into a worldview for Germany:

During my struggle for existence in Vienna I perceived, very clearly that the aim of all social activity must never be merely charitable relief, which is ridiculous and useless, but it must rather be a means to find a way of eliminating the fundamental deficiencies in our economic and cultural life.

Of course, the ‘deficiencies’ would eventually be blamed on the Jewish presence in German life: ‘in my eyes the charge against Judaism became a grave one the moment I discovered the scope of Jewish activities’.

Casting his eye back at himself, organising his growing-up years to suggest an inevitable destiny, Hitler’s self-fashioning is committed to setting up a mission and a vision. His claims that the workers saw his leadership potential and his oratorial skills early are all contributions to this self-fashioning. More importantly, he implies the shared life-growth, pattern and destinies of the Nazi Party and himself.

Rhetoric of Hate, Rhetoric of Purity

Hitler’s oratorial skills which mesmerised and drove millions into endorsing war and genocide are well-known. Mein Kampf itself is a bunch of declarative sentences. A review by William S Schlamm in The New York Times, 17 October 1943, pulled no punches when he linked the text with the execution of its vision:

Adolf Hitler is a poor writer. Even if the Germans were to get away with a lenient peace this coagulated stench will stick to them for the rest of their national history — a fate truly worse than death.

In the first pages of Mein Kampf, Hitler makes his worldview clear, unequivocally: ‘German-Austria must be restored to the great German Fatherland, and not on economic grounds…People of the same blood should be in the same Reich’. As Ralph Manheim, whose 1943 translation is still one of the most widely read, put it: ‘to show that men are not equal is the theoretical purpose of Mein Kampf’.

Mein Kampf suggests that both his life and his writing had an inevitable endpoint: the champion and then leader of the German nation and its people

Even in the first part, Hitler is categorical that ‘On this planet of ours human culture and civilisation are indissolubly bound up with the presence of the Aryan. If he were to be exterminated or become extinct, then the dark shroud of a new barbaric era would enfold the earth’.

Introducing the binary of Aryan versus the barbarian or the Jew, Hitler prepares the ground for hating the Jew. Hitler declares that the entire purpose of the state was the safeguarding, promotion and reiteration of the superior races:

the paramount purpose of the State to preserve and improve the race, an indispensable condition of all progress in human civilisation … with the extermination of the last race that possesses the gift of cultural creativeness, and indeed only if all the individuals of that race also disappeared, would the earth definitely be turned into a desert … indispensable prerequisite for the existence of a superior type of human beings is not the State, but the race, which is alone capable of producing that higher type…The State is only a means to an end … Its end and its purpose are to preserve and promote a community of human beings who are physically as well as spiritually kindred. Above all, it must preserve the existence of the race… As Aryans, we can consider the State only as the living organism of a people….

He continues in this strain endlessly, making it clear that the pure races must define the German state. But this is not enough for, as Michael McGuire in his account of myth-making and rhetoric in Mein Kampf notes, the myth of Aryan superiority is built around the myth of Jewish treachery. For Hitler there are the ‘two contradictory wills at work in the world’, the Aryan and the Jewish (McGuire).

Within the text, hate rhetoric works through a series of powerful metaphors. First, the German nation is conceived of as a body. Secondly, this body is under threat from, or already contaminated by, the Jewish parasites. Blood poisoning, sickness, miscegenation as tropes run throughout Mein Kampf. We see ‘the ‘poison of the foreign races’, the ‘poisoning of the body politic’, ‘poisoning of the popular mind’, the ‘age of racial poisoning’ and their cognate phrases throughout the text. And then there are the direct accusations, constitutive of hate speech:

Look at the injuries which our people are suffering daily as a result of being contaminated with Jewish blood. Bear in mind the fact that this poisonous contamination can be eliminated from the national body only after the lapse of centuries, if ever.

Akin to King James I’s rhetoric of the physician king in Early Modern England, Hitler’s sickness-trope enables the construction of the Jew as a pestilence, and one which demands a physician to excise Jewry in toto, the physician being the Nazi Party led by Hitler. For communications and cognitive linguistics scholar Andreas Musolff, ‘the Nazi metaphor system helped gradually to “initiate” wider parts of the German populace into the implications of the illness-cure scenario as a blueprint for genocide’ — and hence must be taken seriously.

Hitler resorts to the sickness/cure binary as a standard trope to describe the state of the German nation, and its so-called threat, the Jews, casting the latter as poisons, contaminants and pestilence that need to be rooted out

He accuses the Jews of ‘preserving the purity’ of their blood and declares that Germany would fall if Aryans did not do the same for, ‘If nations become impotent or extinct through senility it is because they have failed to preserve their racial purity’. And, in order to tutor the nation to understand the significance of purity, Hitler turns to urgent reforms in education, to which he devotes considerable space.

Educating Aryans, and No One Else

He writes: ‘No boy or girl must leave school without having attained a clear insight into the meaning of racial purity and the importance of maintaining our racial blood unadulterated’. The teaching of history, which he believes is crucial to the discourse of Aryan purity and German nationhood, should be sharply focused: ‘out of the abundance of great names in German history the greatest will have to be selected and presented to our younger generation … become solid pillars of strength to support the national spirit’.

So the state has to control the education system: ‘it is the business of the völkisch State to arrange for the writing of a world history in which the racial problem will occupy a dominant position’. Hitler writes, ranting against diversity, equality and inclusivity:

It does not dawn on the murky bourgeois mind that … it is an act of criminal insanity to train a being who is only an anthropoid by birth until the pretence can be made that he has been turned into a lawyer; while, on the other hand, millions who belong to the most civilised races have to remain in positions which are unworthy of their cultural level.

The bourgeois mind does not realise that it is a sin against the will of the eternal Creator to allow hundreds of thousands of highly gifted people to remain floundering in the swamp of proletarian misery, while Hottentots and Zulus are drilled to fill positions in the intellectual professions.

Training the lower races for critical decision making is useless, for only the Aryans are born to it:

At all critical moments in which a person of pure racial blood makes correct decisions, that is to say, decisions that are coherent and uniform, the person of mixed blood will become confused and take half-measure.

In short, the education system must prepare the pure races to take over the nation, and maybe the world.

Can we presuppose that what Hitler expressed in Mein Kampf was what he truly believed — because, like all memoirists and autobiographers, he was writing opinions that were expedient to hold at that time?

As Joseph Cronin of the Leo Baeck Institute observes in a 2024 essay, most interpret the work based on an assumption that ‘Hitler’s later actions as dictator of Germany were simply the product of his psychological impulses’, adding that ‘the “evidence” of it being the blueprint for Hitler’s crimes only becomes manifest because of what happened later’.

There was no book which deserved more careful study from the rulers, political and military, of the Allied Powers — Winston Churchill on Mein Kampf

Cronin’s scepticism is a necessary antidote to the trend of seeing Mein Kampf as the reason for certain historical events. For commentators such as Albrecht Koschorke, however, the darker the phraseology of the book, the more easily it is absorbed by selective usage in interest groups, which then produces certain consequences. So then, are the contexts of its writing more significant than the contexts of our reading (post-Holocaust)?

And yet, we cannot delink our reading of Mein Kampf from the horrors that followed. Perhaps we are mistaken. Perhaps we overrate the influence of one book, despite it being vitriol in print.

Was this the book that launched a genocide after all?

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Major pipeline leak disrupts water aupply in Hyderabad suburbs

2 mins ago -

Telangana Women Moto Bikers celebrate Women’s Day with vibrant gathering in Financial District

6 mins ago -

IIMC Khairatabad conducts Online Commerce Talent Test with global participation

7 mins ago -

From Lagacherla to Madhu Park Ridge, land acquisition disputes haunt Congress government

12 mins ago -

Smoke emanates from TGSRTC bus in Karimnagar district; passengers shifted safely

22 mins ago -

Government teacher found hanging in Kothagudem; family alleges foul play

26 mins ago -

IHM Hyderabad opens admissions for B.Sc. Hospitality course for 2026–27

58 mins ago -

Sharjeel Imam gets 10-day interim bail in 2020 Delhi riots case

59 mins ago